The Simpsons (Classic): “In Marge We Trust”

“In Marge We Trust” (originally aired 4/27/1997)

In which we should all just be glad God’s not here…

Marge episodes tend to be the smallest-scale of Simpsons episodes, a natural byproduct of her status as the show’s resident grounded straight woman. She isn’t likely to respond to a reinstated prohibition law by becoming a master bootlegger, nor is she about to ask deep, soul-searching questions about the ethics of eating meat or the importance of skeptical inquiry. She can absolutely have adventures—becoming a cop, insinuating herself among the Springfield country club elite, starting her own pretzel business—but even those flirtations with wackiness are born of specific, carefully detailed character beats, almost always to do with her frustrations with the monotony of domestic life. Like her daughter, Marge cares about bringing meaning to her life, but in a distinctly less high-minded sort of way. Mostly, she’s just looking to get through the day with a smile on her face, and it’s hard to begrudge her that when she has to put up with the likes of Homer and Bart.

The set-up for “In Marge We Trust” operates along those lines, with Marge volunteering at the church as a way to bring back some value to the activity, to restore some of the beauty in what could be a profound experience but what is just total drudgery for all involved. The opening church service is taking what has long been the central joke with Reverend Lovejoy—his total yet weirdly judgmental apathy toward everything, give or take model trains—and pushes it to its logical extreme with his lengthy sermon on constancy, sweet, sweet constancy. In several DVD commentaries, Matt Groening has noted that, for all the accusations that The Simpsons is some heathen, irreligious show, he and the writers have generally tried to treat Lovejoy more charitably than the other side characters, presenting him more as flawed than as outright corrupt. Admittedly, Groening would usually make this point mere seconds before Lovejoy did something that was unambiguously wrong and mean-spirited, prompting some frustrated harrumphing from the show’s creator, but it’s still worth noting.

But the show does generally make an attempt to place limits on Lovejoy’s character that don’t exist for some of the other supporting players: It’s hard to imagine him ever displaying the utter evil of Mr. Burns or the incompetent stupidity of Chief Wiggum or the booze-soaked venality of Krusty, but it’s equally hard to imagine him having the kind of sudden positive shift in character that all those characters are capable of (even if those shifts are always reset before next week’s episode). The “bad” Lovejoy of the first half of this episode isn’t really so different from the “good” Lovejoy of the flashbacks and the episode’s conclusion. He’s still someone who came to Springfield to start his ministry because, by the ‘70s, people were once again ready to feel bad about themselves. He’s still someone who uses the free time Marge’s volunteering gives him to rediscover a form of shame that’s gone unused for 700 years. As he tells Ned at the end, the big takeaway he has from all this is just that there’s more to being a minister than not caring about people. There’s a, well, constancy to all that we learn about Reverend Lovejoy that means “In Marge We Trust” gives us one of the most compressed character arcs in the show’s history.

What this means is that The Simpsons can’t go as far as it otherwise might with its typical absurdity. “In Marge We Trust” is an episode composed in minor notes, and while I wouldn’t want every episode to be quite so intentionally understated in its sense of humor, the story works beautifully as a change of pace. In particular, Donick Cary’s script has great fun with pauses. There’s the meta moment when Marge declares that nobody is watching the Simpsons right now, followed by the family sharing some unnerved glances around the room. As reality-bending gags go, this is a fairly muted one; Cary’s script drills a hole in the fourth wall where, say, a John Swartzwelder effort would have flung an incendiary device at it. But it’s in keeping with the tone of an episode where Marge’s entire counseling session with the Sea Captain consists of an increasingly melancholy succession of the word “aye.”

Not all of these little vignettes work: The bit with Lenny and his imaginary wife feels like an homage to hacky sitcoms past, but Marge’s suggestion of cooking Carl a big dinner is such an intentionally mild gag that it barely registers as such. (It doesn’t help that Lenny looks a bit off-model here, though I suspect he just looks and sounds weird outside the familiar context of the nuclear power plant.) But the episode nails the moment with Sideshow Mel, taking the mildest issue of all—a recurring dream in which he’s falling!—and filtering it through his over-the-top delivery and the hushed concern of the crowd. The episode makes a big deal out of that moment without ever letting us forget how unimportant this all is, which leaves room for Reverend Lovejoy’s muted crisis of conscience. It’s fitting that this strain of understated comedy hits its apex when Lovejoy has his conversation with the saints, who unlike the mere mortals inject some real passion into the proceedings. The reverend’s answer that he had the vestibule recarpeted really is the most achingly mundane response imaginable, and the saints’ outrage is all the funnier because Lovejoy’s banal answer actually kind of makes sense in the context of this particular episode.

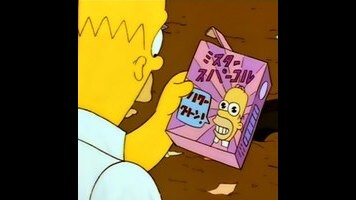

Ah, but what of the episode’s subplot and by far its most iconic element, Mr. Sparkle? That storyline has a little more zip to it than the main narrative, if only because it’s hard to not have fun with a Homer caper story that also features Bart and Lisa, but it too doesn’t necessarily strain for big laughs. Some of that is down to the construction of the subplot, as Homer’s appearance on the box of Japanese detergent is so inexplicable that the family isn’t even sure how to respond to it; Homer’s whimpering at various points suggests the paranoid disquiet of someone whose life is unraveling around him for reasons he can’t even begin to fathom, so we don’t get Homer raging for or against some cause with his usual violent certainty.

But again, the episode makes the most of the quiet, as when he goes to the library to get the phone number for the Mr. Sparkle manufacturers. The episode painstakingly lays out every aspect of the phone call gag, with Homer unconvincingly lying to the librarian that, immediately after getting the Hokkaido phone book, he needs to make a local call. Another episode might have gone for a confrontation between Homer and the librarian, but Steven Dean Moore’s direction just keeps the librarian in the background as Homer dials for what feels like forever, with the worker shooting one curious glance before shrugging and walking off. The humor here rests on all the space given to Homer’s dialing, on the old comedic principle that something can be funny for a little bit, stop being funny if it goes on too long, and then gets really funny if it just keeps going.

The actual Mr. Sparkle commercial plays on the perceived incomprehensibility of Japanese popular culture, a comedic goldmine that has been well and truly excavated in recent years but I believe represented still relatively unexplored territory back in 1997. Either way, the Mr. Sparkle commercial is such a damn masterpiece that there’s little I can add to it. In an episode that is otherwise downright mild-mannered by Simpsons standards, the Mr. Sparkle commercial is a giddy explosion of surrealism, a bit of perfectly constructed nonsense in which every little scene is utterly insane yet flows with perfect anti-logic from what preceded it. Sab Shimono’s exuberant voiceover as Mr. Sparkle is the perfect counterpoint to the ornately overwritten translation of the English subtitles. Still, my favorite detail might be what comes directly before the commercial, with the Mr. Sparkle owner addressing American investors by saying they are looking to sell the detergent in their “home prefecture.” Much like Homer’s earlier conversation with Gedde Watanabe’s factory worker, that line is a perfect distillation of the mutual misunderstandings and cockeyed assumptions between American and Japanese culture, something Donick Cary would return to in the tenth season finale, “30 Minutes Over Tokyo.”

As for the resolution of the Reverend Lovejoy plot, this episode is in what really might be the unique position of placing a heavy focus on Ned Flanders without once acknowledging Homer’s hatred of him. But then, Lovejoy is more than happy to pick up the slack on that front, his original disaffection the direct result of dealing with Flanders’ constant, meaningless concerns about coveting his own wife, being insufficiently meek, and possibly swallowing a toothpick. The search for Ned and the showdown with the baboons both benefit immensely from the quieter comedic approach of the rest of the episode, as this allows “In Marge We Trust” to get away with a wonderfully half-assed investigation, one involving both a hunted Ned to only offer part of a gas price as an identifying featuring and the Donny of Donny’s Discount Gas offering a clichéd “I see a lot of things” before acknowledging that, yes, he saw the thing Lovejoy and the Simpsons are looking for. Again, “In Marge We Trust” doesn’t overplay the self-aware crumminess of this plotting, which proves crucial to its success.

Lovejoy’s fight with the baboons works along similar lines. His commandeering of the train is a nice tip of the hat to his love of model trains, and Steven Dean Moore and his team design the train so that it’s just a hair too small for Lovejoy to sit in without looking ridiculous. The fight has all the makings of previous epic Simpsons confrontations between unlikely combatants—think something like Abe and Burns’ fight in the “Flying Hellfish” episode, as that one is portrayed as a relatively serious action showdown—but again “In Marge We Trust” is content to undercut itself, with Lovejoy merely uncoupling the rear cars to dispatch some of the attackers. Admittedly, he does get one final fight in with the baboon, complete with the excellent battle cry “Say your prayers, you heathen baboon!” Like the Mr. Sparkle commercial, that burst of over-the-top craziness is made all the funnier because it’s such a counterpoint to all that’s come before, and it makes Lovejoy’s triumphant closing sermon all the sweeter.

“In Marge We Trust” is often rated very highly, particularly by the show’s creative team: Matt Groening ranked this his fifth favorite episode on the occasion of the show’s 10th anniversary—which now represents less than 40 percent of the show’s total output, but still—and season eight co-showrunner Josh Weinstein declared this both one of the best and one of the most underrated episodes on the DVD commentary, which sounds about right. Coming into this episode, I remembered it mostly just as “the Mr. Sparkle episode”; admittedly, the word “just” there is used quite wrongly, as the episode could have been 20 minutes of static surrounding the Mr. Sparkle commercial and still ranked as one of the show’s all-time greatest episodes. But what makes “In Marge We Trust” special is that it does something so different from almost any other episode. Weinstein and his showrunner partner Bill Oakley often mention on the commentaries that they wanted their two seasons to keep the focus squarely on the Simpson family, yet this episode breaks that mold, not just building the main story around Lovejoy but also filtering the episode’s comic sensibility through his own deadpan worldview. I’m glad not every episode is like “In Marge We Trust,” but I am far, far gladder that this one is.

Stray observations:

- “Well, it was a good ride while it lasted. Come on, kids, let’s go home.” “We are home.” “That was fast.” Another really fun, understated subversion of expectations. If it weren’t for the joy of the Mr. Sparkle commercial, that whole subplot would play like an intentionally pale imitation of a typical Homer adventure plot.

- “You’ve got to get him out of there.” “Geez, I’d like to, but if they don’t kill the intruder it’s really bad for their society.” Yep, that seems completely plausible.

- “Hey, Mr. Sparkle! Mr. Sparkle!” “Konnichiwa.” I love Homer embracing his weird pseudo-celebrity status. He gets his happy ending after all!

- Next week: I’m actually just subbing in for your regularly scheduled reviewer, Erik Adams, so I have no idea who is up next week! But I do know “Homer’s Enemy” is up next, and I’m guessing there’s going to be just a little bit of stuff to discuss about that one!