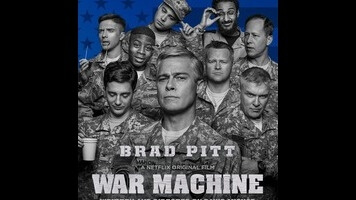

The nicest thing one can say about David Michôd’s maladroit, Netflix-produced Afghan War satire War Machine is that despite the high statistical likelihood of its existence (A-list star, bestselling source material, obvious political angle, semi-established writer-director), nothing in the movie suggests that it was made to please anyone. Whether it’s intentionally off-putting is a different matter. An adaptation of the late Michael Hastings’ non-fiction book The Operators: The Wild And Terrifying Inside Story Of America’s War In Afghanistan (itself expanded from Hastings’ 2010 Rolling Stone article “The Runaway General”) that bears almost no resemblance to Michôd’s earlier films Animal Kingdom and The Rover, the film casts Brad Pitt as General Glen McMahon, a fictional stand-in for Stanley McChrystal, the onetime commander of NATO forces in Afghanistan whose career was destroyed by Hastings’ all-access profile. This is the most bizarre lead performance of Pitt’s career, as he plays McMahon as a stroke victim doing the world’s worst impression of George Clooney. Just to make it clear at the outset how broadly he intends to pitch his send-up of gung-ho American interventionism, Michôd introduces McMahon taking a dump at the Dubai International Airport and then proudly marching though the terminal.

There is a lot about War Machine that is equally cartoonish, from McMahon’s meetings with Afghan president Hamid Karzai (Ben Kingsley), whose attention appears to be largely focused on getting the Blu-ray player in his palace to work, to the mocking and occasionally distracting score by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis. But what is Michôd really aiming for? The tone of War Machine is overwhelmingly smug (“Ah, America,” begins the voice-over narration by the film’s Hastings stand-in, played by Scoot McNairy), but the film is short on specific targets and its reading of the state of modern war is as dry as sand. His face balled up like a fist, McMahon is a caricature of American might who in no way resembles the real Stanley McChrystal (who looks and sounds more like Alan Ruck, cast here as one of McMahon’s political nemeses), but who has been clumsily inserted into several real-life public-relations fiascoes. Thus, War Machine puts itself in a peculiar lose-lose scenario: It’s too hamstrung by facts to get within spitting distance of the sort of Strangelove-ian satire of backroom political idiocy where McMahon and the movie’s version of Karzai truly belong, but also too clobbering, uncontrolled, and secluded from reality to pass muster as a parody of the actual events and personalities involved.

The idea behind the film is not bad on paper. While the usual targets of geopolitical satire are stuffed shirts, weasels, and smooth talkers, the butt of the joke here is McMahon, an undiplomatic, gut-instinct soldier’s soldier who runs his office like the head coach of a over-budgeted college football team, assisted by a team of lackeys, played by the likes of Topher Grace (as his sleazy public-relations guru) and Anthony Michael Hall (as a character based on Mike Flynn). Michôd does manage to wring some solid laughs early on out of the American military presence’s failures at improving its image with the people of Afghanistan. (As one local translator helpfully explains to McMahon and his team, “They call us ‘motherfucker’ all the time, and it is considered in our culture a very bad thing to fuck your mother.”) But as War Machine inches closer to McMahon’s downfall, it becomes more ham-fisted. Perhaps a more deftly made film would have made more than a self-satisfied observation out of the arbitrary circumstances of its main character’s ouster. Michôd’s previous two films have been skillful and grim thrillers produced on low budgets in his native Australia; here, he ironically parallels his subject by planting his foot on unfamiliar ground with no exit strategy.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.