The Snyder Cut is a much longer Justice League, but not a better one

There’s no alternate reality, no Else- or Bizarro World, where the Justice League premiering on HBO Max this week is the only version, the “official” Justice League. Imagine that Zack Snyder had stayed at the helm of the DC crossover event he was orchestrating—that family tragedy hadn’t torn him away from the project and that Warner Bros. hadn’t taken his absence as excuse to reconfigure the whole film against his wishes. Even under those “what if” circumstances, would multiplexes really become home to a four-hour, R-rated team-building exercise for comicdom’s most famous spandexed heroes? This, the fabled Snyder Cut of popular (or at least persistent) demand, is a movie that could only have risen from the rubble of another: It’s a maximalist superhero spectacular, twice the length of the previous iteration, that exists because of the troubles that plagued its production, not in spite of them.

At this point, the story of Justice League’s rocky path to release (and now recut rerelease) has shadowed the one the film tells. It has as many twists and turns, as much defeat and resurrection, as “The Death And Return Of Superman,” one of the comic book story arcs that inspired Chris Terrio’s original screenplay. If nothing else, seeing this belated director’s cut clarifies what Joss Whedon brought to the table (beyond an apparently toxic work environment) when he stepped in to rewrite and reshoot whole passages after Snyder’s departure. Released in 2017 to what might euphemistically be described as a general lack of enthusiasm, the Whedon-supervised cut of Justice League was a clear product of compromise, committee thinking, and clashing sensibilities. It’s clearer than it’s ever been that the writer-director of The Avengers was hired to Marvelize a Zack Snyder movie, with all the rapid-fire quips, sitcomish interpersonal conflict, and flat televisual action that implies.

For better or worse, Zack Snyder’s Justice League is a reclamation, and a blow struck for unchecked artistic ego in the face of the endless (if maybe sometimes sensible) notes of meddling studio execs. No one would confuse this cut, with its hero-pose tableau, Nick Cave needle drops, and depressive caped crusaders, for the work of any other filmmaker but the one who turned The Man Of Steel and The Dark Knight into dueling, sulking Martha’s boys with a concerningly wavering respect for the sanctity of human life. Snyder hasn’t just realized his original vision for Justice League, the third in a trilogy of dour, bombastic, occasionally striking vehicles for the world’s finest and friends. He’s expanded it, too, spending a reported $70 million of new Warner Bros. money on a reconceived finale and a convoluted flex of an epilogue that manages to squeeze several more faces, old and new, into an already overcrowded ensemble.

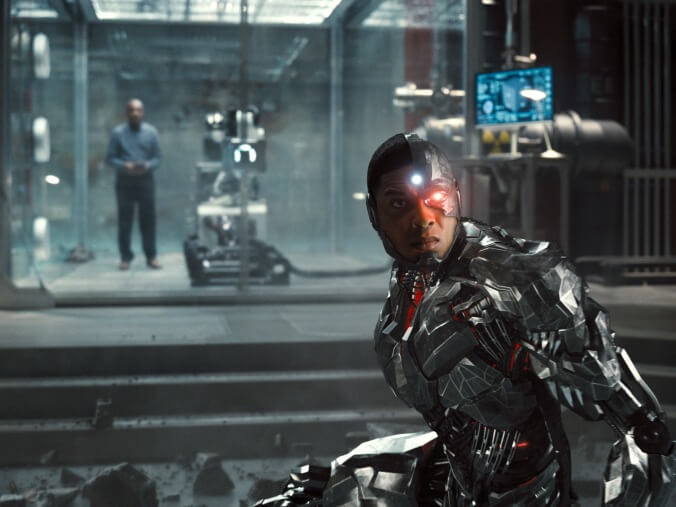

From the jump, it’s plainly his. Just as Snyder’s Batman V Superman started with a different angle on the climax of his Man Of Steel, so too does his Justice League begin with another look at the moment Superman (Henry Cavill) fell on the ashen outskirts of Metropolis. In basic plot outline, Justice League hasn’t changed much. Set in the aftermath of an icon’s demise, this is still the story of how Bruce Wayne (Ben Affleck) and Diana Prince (Gal Gadot), a.k.a. Batman and Wonder Woman, assemble a team of fellow “metahumans” to protect the Earth from an extraterrestrial conqueror. The major difference is that this narrative unfolds over an exhausting 240 minutes of running time, allowing for extended flashbacks, heftier subplots, signature dream sequences, and longer detours into the chintzy fantasy realms of Atlantis and Themyscira. It takes two whole hours, the entire length of the previous Justice League, to even get seafaring Aquaman (Jason Momoa), super-fast The Flash (Ezra Miller), and mechanical Cyborg (Ray Fisher) into the same room together.

There is some addition by addition. Fisher’s Cyborg, whose hybrid man-machine body once made him a walking metaphor for Justice League itself, gets an actual character arc this time—and an origin story with shades of the Dr. Manhattan sequence in Watchmen. (Although he remains the most thinly sketched of the League, you can see now what the guy’s doing here.) On a whole, though, the Snyder Cut is shapeless and interminable. It has no rhythm; despite the ostensible organizational presence of chapter titles, you could conceivably reshuffle the events of the first half without changing the effect at all. Snyder throws all of his footage back into the mix, with little apparent awareness of what’s vital and what’s superfluous. Did we need three whole glorified deleted scenes of boring space invader Steppenwolf (Ciarán Hinds, unrecognizable in voice and appearance) teleconferencing his progress to a flunky of future franchise heavy Darkseid? Batman, the closest thing Justice League has to a main character, disappears for half-hour stretches. Meanwhile, Lois Lane (Amy Adams) sulks around the edges of the film, her grief still feeling like an afterthought, even as it’s granted double the narrative real estate.

There’s no such thing as a small moment in a Zack Snyder movie. Which means that there’s no such thing as a big one. Every scene is directed the same way, as though it were taking place on Mount Olympus: A wet mop hits the floor like Excalibur, while a sesame seed plummets for a small eternity during an at least relevantly slow-mo (and restored) introduction for Miller’s neurotic speed-demon rookie. This is, to be fair, preferable to how Whedon staged everything: You don’t need x-ray vision to see the difference between this cut’s version of the attack on Diana’s homeland—warrior and demon bodies swarming over each other, a grand mess of limbs—and the more perfunctory direction of the sequence in the theatrical cut. Snyder is, at minimum, a gifted image-maker, and if he sees little but mythic cool in his comic book source material, at least he gets the visual appeal of these heroes, looming like giants of splash-panel or rock-album lore. If only his CGI action scenes inspired a little excitement on top of the sporadic awe; the reshot climax, now a moodily nocturnal showdown, is busier and more majestic but comes down again to digital avatars zipping weightlessly across the frame, bellowing, “My man.”

So is it a better movie? It’s certainly more its own movie: While this remains the most relatively lighthearted of Snyder’s forays into a world of capes, cowls, and messiah complexes (The Flash no longer rants about brunch, but he’s still funny), the incongruous, studio-mandated barrage of imitation Marvel banter is gone. This Justice League looks less cheap and anonymous, too; even the overlapping footage is improved in the new cut, betraying how much color correction matters in films like this, regardless of how glumly narrow their palette may be. But there’s a trade-off here, and it’s the loss of the genuine humanity Whedon brought to this world—a personality and vulnerability that just doesn’t square with Snyder’s conception of these characters as fundamentally godlike beacons of strength and power. That means Affleck’s guilt-stricken Bruce Wayne no longer reflects on the way that Kal-El might have been more human than him; it’s a smart, affecting scene sadly lost in the de-Whedonizing. Likewise, any traces of Cavill’s more characteristically heroic and upbeat Superman. Getting to see the Man Of Steel actually smile was one welcome rupture of the Snyder game plan, one fix now missed.

The reality is that Justice League’s problems go beyond who was behind the camera. The villain is still generic and silly-looking. The plot is still assemble-the-team boilerplate, hinging on the hunt for glowing MacGuffins with a goofy name. Gadot’s Wonder Woman is still subjected to some slobbering objectification from her new teammates—proof that in at least one respect, Snyder and Whedon saw eye to lascivious eye. And, on the most basic level, it was still a miscalculation to try to rush the Avengers formula of success, to stuff introductions for so many new characters into one movie instead of giving them their respective starring vehicles first. That there’s ample elbow room for each of the film’s marquee attractions (you get to see Cyborg win the big high school football game!) just means that Justice League has become an inelegant everything-and-the-kitchen-sink version of itself instead of a ruthlessly streamlined, bastardized blockbuster. Faithful fans may very well cherish this unfiltered, super-sized helping of Snyder: The ironic happy ending to their cause is that the one film of his that he truly lost control of has been reborn into his magnum opus of excess, at least by volume. For the rest of us, a superior cut of Justice League remains out of reach, unreleased.