The South got something to say in Chronicling Stankonia

“It’s like this though,” André Benjamin nervously shouted over the chorus of boos. “I’m tired of close-minded folks, you know what I’m saying?” As one half, with Antwan “Big Boi” Patton, of the Atlanta-based hip-hop duo OutKast, Benjamin had just won the 1995 Source Award for Best New Rap Group. The Madison Square Garden crowd, unwilling to budge from their bicoastal sensibilities to applaud this pair of defiantly Southern rappers, was not happy. “We got this demo tape but don’t nobody wanna hear it,” Benjamin continued.

Released the year prior, OutKast’s debut album, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik (1994), was much more than a demo. Like most rap records of the period, it toasts the scene’s pimps, players, mack daddies, and hustlers, but also contains the cultural and historical awareness to remind listeners of the shameful fact that the Confederate battle flag still flew over the state capitol (it would finally be removed in 2003).

As the boos rained down, and Chris Rock looked on in disbelief, Benjamin, clad in a Prince-ian purple dashiki, threw his right hand in the air to emphasize his last words to the disgruntled crowd: “The South got something to say.”

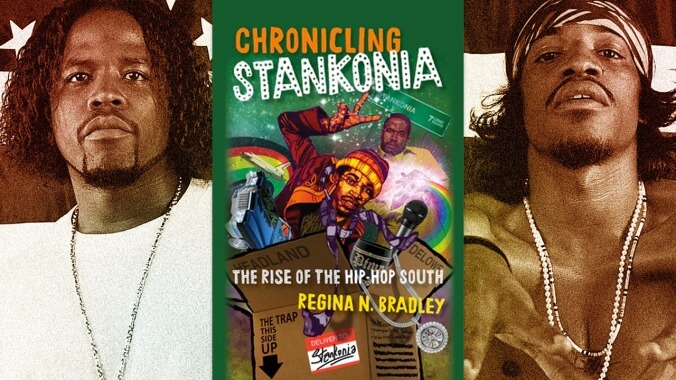

Benjamin’s instantly iconic declaration became a rallying cry for a generation of Southern rap fans. Those six words have been dissected in countless essays, books, an NPR Music project, and now Regina N. Bradley’s Chronicling Stankonia: The Rise Of The Hip-Hop South. Bradley, a professor of English and African diaspora studies, is less interested in writing a biography tracing the short reign of the South’s greatest rap group—Big Boi and the renamed André 3000 went on hiatus in 2006, though a 40-festival tour followed eight years later—and more fascinated with why OutKast matters. “Their lyrical whimsicality and sonic and cultural experimentation with their southernness,” she writes, “situates them as the epicenter of recognizing a collective… contemporary southern black cultural landscape.” Simply put, much of what the Black South gots to say today is due to this duo.

Although those boos eventually turned into critical acclaim and commercial riches, OutKast seemed destined to live apart from the pop music mainstream. That dichotomy is embedded not only in the duo’s name, as Bradley points out, but also in Big Boi’s and André’s stylistic juxtapositions. They are outcasts from the dominant bicoastal rap aesthetics, outcasts as young Black men in the South, and outcasts from each other—two rappers with vastly contrasting voices, personalities, and sartorial choices (try claiming the same for Georgia’s hip-hop trio Migos). That “OutKasted” mentality is best expressed on their second album, ATLiens (1996), where they portray themselves as literal aliens, Southern extraterrestrials with a taste for “fish and grits,” while staying true to the “pimp shit.”

The best parts of this short book of essays find Bradley reminiscing about her own outkastedness. She fell in love with the duo in 1998, soon after moving from northern Virginia to Albany, Georgia, at the age of 14. That summer’s local hit, Goodie Mob’s “Black Ice (Sky High)” finds OutKast stealing the song from their Dungeon Family comrades. Big Boi steps in at the two-minute mark, rhyming faster than the beat, as if he has somewhere better to be. Delivering the track’s anchor, André finds room to reference Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, nearly all the colors in the spectrum, the Atlantic slave trade, and seemingly half a dozen other subjects in less than 30 seconds.

My own initiation came later that year, with the release of the group’s third album, Aquemini, named for the mashup of Big Boi’s and André’s zodiacs. The bluesy “Rosa Parks” was the album’s radio smash, but fans know that it’s the title track, alongside the two-part “Da Art Of Storytellin,’” that best spotlights Aquemini’s main theme: the fragility of interpersonal relationships, be they with friends, family, or lovers.

OutKast frequently displayed a sensitivity missing from most modern music. The title of their fourth album Stankonia (2000), Bradley writes, is a “useful metaphor to speak the messy truth,” or stank, of life. Rap often means never having to say you’re sorry, but that’s exactly what the newly renamed André 3000 does again and again and again on the duo’s first number one hit, “Ms. Jackson.”

OutKast’s post-millennial output—the combined solo record Speakerboxxx/The Love Below (2003) and a companion piece to their 2006 film, Idlewild—does not rise to the level of their first four albums. But, Bradley maintains, Big Boi and André continue to influence a new era of outkasted artists—musicians, filmmakers, and authors, most notably two of the best American writers working today: Kiese Laymon and Jesmyn Ward. The South still got something to say, or, as Big Boi raps on “The Way You Move,” one of the duo’s biggest hits, “We never relaxing, OutKast is everlasting.”