The Star Wars franchise—even the prequels—is a work of weird genius

With Run The Series, The A.V. Club examines film franchises, studying how they change and evolve with each new installment.

Imagine that there’d never been a Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope—under any title. No The Empire Strikes Back. No Return Of The Jedi. Now say that it’s the late 1990s, and George Lucas is a reclusive Terence Malick-like figure who hasn’t directed a movie since the impressive one-two of 1971’s THX 1138 and 1973’s American Graffiti. He’s done some producing, and collaborated with his old friend Steven Spielberg on Raiders Of The Lost Ark and its sequels, but otherwise he’s stayed idle, right up to the moment when word leaks out that he’s writing and directing a throwback science-fiction trilogy, inspired by pulp comics, world mythology, samurai pictures, and the serials he loved as a kid.

In this scenario, what do people end up thinking about The Phantom Menace, Attack Of The Clones, and Revenge Of The Sith? If they exist in exactly the form they’re in right now, are they still massive worldwide hits? Do critics and genre fans still roll their eyes at them? Do they even make sense?

How people answer those questions may depend on how they feel about the Star Wars prequels in the first place. Those who think that Lucas spoiled his own creation with bad casting, painful comic relief, and overcomplicated mythology will likely never be persuaded that those movies work remarkably well on their own terms—that they’re marvelously imagined and plotted, and shot and constructed by a one-of-a-kind genius. But for prequel apologists… Well, it’s still a pretty tangled situation.

The problem with trying to approach the Star Wars series in any kind of fresh, forgiving way is that Lucas has done so much to flummox even his biggest supporters. His continued tinkering with the original trilogy to bring it more in-line with the look and narrative of the prequels means that even the previously powerful nostalgic kick of Episode IV has been dulled by scribbled-in CGI. It’s hard to judge any of these films on their own merits any more. They’re all too interconnected, with the worst elements snaking into the best. And that’s not even taking into account the pervasive, at-time-insidious influence of Star Wars on the Hollywood blockbuster industry, which makes defending the movies against skeptics feel a lot like “punching down.” This franchise has made billions of dollars, and introduced characters and concepts that are beloved worldwide. It’d be disingenuous to call Lucas underrated.

And yet, he kind of is. What gets missed in all the lamentations about how Star Wars changed American cinema for the worse is that very few of the filmmakers who followed in Lucas’ footsteps have been able to instill awe the way he does, or build such a rich mythology, or put together action sequences so craftily. The others aren’t weird enough. They don’t have Lucas’ peculiar combination of film-school snobbery and unchecked preadolescent id.

Regardless of the numbering, the best way to watch the Star Wars series is still to start with 1977’s A New Hope and 1980’s The Empire Strikes Back. The former is the simplest, most direct introduction to what this story’s really about: the adventures of a farmhand named Luke Skywalker who discovers that he has an important role to play in the ongoing battle between multiple independent interplanetary cultures and the seemingly all-powerful Empire that seeks to subjugate or eradicate them. The sequel then complicates that story by revealing that Luke is the long-lost son of the Empire’s most ruthless commander, Darth Vader, and that his growing mastery of the mystical power known as “The Force” could leave him more open to manipulation. Beyond establishing the Star Wars universe and then delivering the plot’s most startling and significant twist, episodes IV and V are the series’ only A-grade/five-star entries. See those two, and the other four become more urgent.

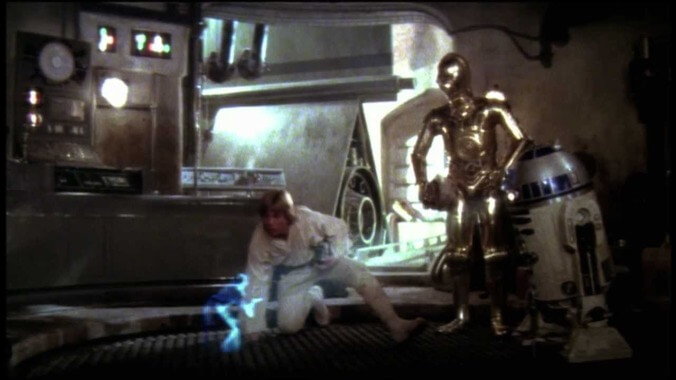

Watching A New Hope again now, knowing everything that came after, it’s remarkable how little actually happens in the movie—and how much Lucas and his effects team are able to suggest with only a few sets and set-pieces. After an opening sequence aboard an imperial starship, introducing Darth Vader and Rebel Alliance stalwart Princess Leia, the film more or less settles onto the planet Tatooine for the next hour, using the arrival of mechanical “droids” C-3PO and R2-D2 to guide the viewer through a strange world of freaky-looking creatures and robots. Along the way we meet Luke, and reclusive ex-Jedi Knight Ben Kenobi, who helps the young Skywalker hire rogue star-pilot/smugglers Han Solo and Chewbacca. That’s the first half of the film. After the heroes fly off Tatooine in Solo’s rickety ship the Millennium Falcon, they get captured by the Empire’s moon-sized doomsday machine the Death Star, and their escape takes up about a half-hour of screen-time. Then the last half-hour covers the Rebels’ attack on the Death Star. That’s the entire movie. Yet between all the chases and blaster-fights, Lucas teases out the larger history of an unsettled galaxy, while recombining the best pieces of old WWII pictures and Flash Gordon.

The Empire Strikes Back is an even better film, because with more money and more confidence—coupled with the tempering influences of director Irvin Kirshner and screenwriters Leigh Brackett and Lawrence Kasdan—Lucas had the resources to build on what he’d already accomplished. Again, the movie primarily only features a few locations: the icy planet of Hoth, the swampy planet of Dagobah, and the Cloud City of planet Bespin. But the addition of Jedi Master Yoda and Han’s duplicitous old friend Lando Calrissian to the cast vexes the heroes in ways that add dimension and grayer shadings to their characters. The big action sequences are more white-knuckle, the cross-cutting between locations more assured, and the big revelation that Luke—like his father—might follow his worst impulses and be seduced by “the dark side” makes even the small victories feel hollow. A New Hope lured audiences into the Star Wars universe, but the philosophical and mythological implications of The Empire Strikes Back gave those fans a lot to chew over, sparking geeky conversations that continue today.

The best time to jump into the prequels is immediately after New Hope and Empire, for a couple of reasons. The latter’s dark ending suggests that the troubles in the Skywalker family were long in the making, which means episodes one through three serve as an extended (okay, over-extended) flashback, filling in the details of what went awry. Also, by design, the prequel trilogy ends on a sour note, revealing the birth of Darth Vader and the death of the Republic. Following those three films with Return Of The Jedi allows the series to have a more upbeat end. (Whether it should end that way is another matter entirely. But more on that in a moment.)

The other advantage to slotting 1999’s The Phantom Menace right after The Empire Strikes Back is that it clarifies what Lucas’ most-maligned film has in common with his two most beloved. Don’t misunderstand: The Phantom Menace earns a lot of the ire directed toward it over the past 16 years. Lucas’ commitment to recreating the vibe of old B-movies led to him creating alien characters who come across as gross ethnic stereotypes; and an overemphasis on appealing to children brought the annoying (and, again, kind of racist) slapstick simpleton Jar-Jar Binks, as well as a kid version of Anakin Skywalker who’s not all that appealing. And then there’s the general wonkiness of the film, which overcomplicates the “light versus dark” plainness of A New Hope, working in explanations that involve arcane bureaucracies and junk science.

Yet The Phantom Menace is also the fullest of the six Lucas-guided Star Wars films, with more plot, more characters, and more action. And it’s great action. The underwater monster-dodging, the pod-racing, and the simultaneous climactic stand-offs in space and on the ground are all as good or better than anything that had come before in a Star Wars film. As for the stiff acting and corny dialogue… well, this is where watching The Phantom Menace in such close proximity to A New Hope makes a huge difference. Lucas has always had his quirks when it comes to the acting in these movies, not unlike how David Lynch or David Mamet prefer a certain flatness (albeit with entirely different intentions).

The problem is that some actors—like Alec Guinness and Liam Neeson—can survive Lucas-ification, and others get crushed by it. Over the course of the prequels, Natalie Portman’s Padmé Amidala wavers back and forth between being compellingly constrained and just wooden (although her eye-popping costumes and hairstyles help keep the character magnetic, even at her blankest), while Jake Lloyd and Hayden Christensen have a rough go of it as Anakin in their respective films. The inability of Lucas and Christensen to figure out how to make the future Darth Vader both charismatic and dangerous almost sinks 2002’s Attack Of The Clones, which is supposed to be anchored by the romance between Anakin and Padmé. It doesn’t help either that the movie features an epic final clone-vs.-droid-vs.-Jedi battle that starts out stunning but runs on way too long, as if trying to compete with the excesses of the contemporaneous Lord Of The Rings trilogy.

But even though Attack Of The Clones is the draggiest of the Star Wars movies, it still has Lucas’ enjoyably chunky plotting, where the characters embark on little adventures that have their own twists and turns (similar to the “chapters” in a serial). Plus, the level of detail in each background pays dividends in one of the series’ best sequences, where Anakin and Obi-Wan Kenobi thwart an assassination attempt on Padmé and then chase the killer through the busy airborne highways of Coruscant—moving at any moment through vehicle-packed x-, y-, or z-axes in their hot pursuit.

The last of the prequels, 2005’s Revenge Of The Sith, doesn’t get talked about as much as it should, in part because a pervasive Star Wars fatigue had set in among critics by the time it was released—and in part because, again, Christensen looks overmatched by the demands of playing a good guy who turns corrupt. (The film’s signature moment, where Anakin is reborn as Vader, has been widely mocked, although it actually connects well as a tip-of-the-mask to old Universal monster movies.) But for those who stick it out with the prequels, and are willing to give Lucas the benefit of the doubt, Revenge Of The Sith makes for a magnificently moody send-off to the cycle, with less intricate plotting but more fatalism. This is the Empire Strikes Back of the prequels, undercutting the surety of what came before by suggesting that “the chosen one” can be evil, and that the systems we put our faith in can be converted into the tools that destroy us. (Lucas literalizes that idea in a sequence that sees newly anointed Emperor Palpatine flinging the Republic’s senatorial boxes at Yoda.)

Moreover, for anyone who watches the films in IV–V–I–II–III–VI order, Sith makes Return Of The Jedi look a lot better. In the context of the original trilogy, Jedi has always been a bit of a letdown. It’s hampered by the thinnest plot of the entire series, consisting of just one long introductory rescue caper on Tatooine, followed by a feature-length mission on and around the forest moon of Endor. Worse, it softens the hard choices laid out in Empire, suggesting that it’s actually fairly easy for Han to avoid paying the price for the sins of his past, and for Luke to get what we wants without turning evil. But when placed right after the grim Sith, Jedi is more a relief, bringing back beloved characters and giving them a long-delayed win. Even those fuzzy scamps the Ewoks don’t seen so insufferable after three films’ worth of Jar-Jar.

There’s a lot that could be said about the offscreen business of Star Wars. Gary Kurtz, who produced A New Hope and The Empire Strikes Back before leaving the series over creative disagreements, has said that after the first movie Lucas became more concerned with merchandising than storytelling. It’d be easy to view a lot of the creative choices from Empire onward through the lens of that criticism. For one thing, it’s hard at times to pinpoint exactly what Lucas means to say with these films, which have such a muddled take on spirituality, government, and militarism that people all across the political spectrum can read the franchise as a metaphor for whatever they happen to believe. The truly cynical (or those willing to be generous to Lucas’ artistic intentions) could even see the prequels as the creator’s long cry of despair, lamenting how easy it is for ideals to be twisted into something mercenary.

But when it comes to big cultural events like the Star Wars movies, we may be too quick to grade “pass/fail.” The Star Wars prequels are deeply flawed, but even their glaring imperfections bear the mark of the man who made them. They’re not bland. They show real ambition. And technique? They’ve got that in spades. Given the way that 21st-century Hollywood has put so much of its collective efforts into impersonal, assaultive franchises that keep demanding more money from fans just to get something approximating a complete story, we shouldn’t be so quick to scoff at movies that each have a beginning, middle, and end, and are threaded through with skillful filmmaking and funky obsessions.

As for Kurtz’s other complaint about Lucas, that he sold out his original story’s more sobering themes for the sake of a happy ending… well, that depends on what counts as the “big finish” for Lucas’ Star Wars. If it’s Return Of The Jedi, then sure, maybe it’s all as sunny as a day on Tatooine. But right now, the last Star Wars film written and directed by Lucas is Revenge Of The Sith, which ends in betrayal and devastation and seems to reflect its creator’s often dour and defensive public persona.

All of this is in the franchise: thrills, beauty, pathos, and gaffes. There are multiple paths that fans can take through these stories. What we take away from Star Wars depends a lot on where we start, where we conclude, and what we choose to see along the way.

Final ranking:

1. The Empire Strikes Back

2. A New Hope

3. Revenge Of The Sith

4. Return Of The Jedi

5. The Phantom Menace

6. Attack Of The Clones