The Stones’ Sticky Fingers invented Southern rock

Permanent Records is an ongoing closer look at the records that matter most.

If rock ’n’ roll was the offspring of country music and rhythm & blues, country was the kind of high-strung hardass parent who kicks their kid out of the house for hanging out with the wrong crowd. In this case, that crowd would include the folky hipsters and foppish Brits who hijacked the genre after its first wave, chock full of Southern white boys, crashed. As rock became increasingly urbanized and entangled with the burgeoning counterculture, the styles’ estrangement grew more intense, and country’s identity became steadily more defined by a reactionary conservative worldview and the aggressive, shit-kicking Bakersfield sound, which combined to produce such notorious era-defining anti-hippie hits as Merle Haggard’s “Okie From Muskogee” and “The Fightin’ Side Of Me.” (Country’s relationship with black music, meanwhile, was equally dysfunctional.)

Like a lot of people with fractured relationships with their parents, rock still sought country’s approval even as it rebelled against its values, and despite country’s condemnation of their music and their lifestyle, rock musicians repeatedly returned to its influence throughout the ’60s. The Beatles used twangy guitars and country songwriting tropes well into their acid phase. The California psychedelic scene kept the Old West musical mythos alive even as country-western abandoned it, and got enough out of hand to produce a brief but intense fad for jug bands (including one that eventually metamorphosed into The Grateful Dead). And Gram Parsons spent his tragically truncated life and career trying to get rock and country to reconcile over their mutual interests in old-fashioned romance, soft-libertarian individualism, and substance abuse.

Parsons found an enthusiastic partner in this mission when he fell in with Keith Richards in the summer of 1968. Both musicians were in a state of transition at the time. Parsons had recently split with The Byrds over his objections to a planned South African tour and a deep-seated disagreement with Roger McGuinn over his role in the band. Richards was struggling to figure out The Stones’ next move after a chaotic period of escalating problems with drugs, police, and internal conflicts that culminated in the hacky Sgt. Pepper’s knockoff Their Satanic Majesties Request. Parsons and Richards had both independently decided that the way out of their situations was a retreat away from the excesses of the psychedelic scene and into the rootsy authenticity of country music, and had already made progress in that direction by the time they became best buds—Richards had Beggars Banquet in the can and Parsons already had the basic concept for The Flying Burrito Brothers sketched out in his head. By the time The Stones began working on Sticky Fingers in earnest nearly two years later the Parsons-Richards partnership had crystallized. Their shared goal had expanded from reconnecting rock with its country roots to somehow synthesizing all of Southern music–not just country and rock ’n’ roll, but also soul and blues—and injecting it with the glammed-up hippie drug-freak persona the pair had been diligently developing.

According to Ben Fong-Torres’ Parsons biography Hickory Wind, Mick Jagger felt threatened by Parsons’ friendship with Richards, as well as the outsider’s growing musical influence on his creative partner. (Although he did admit that Parsons was “one of the few people who really helped me to sing country music. Before that, Keith and I would just copy off records.”) Whether it was jealousy or just his innate hamminess, Jagger’s contributions to the Parsons-inspired dive into all things Southern walked a precarious line between homage and flat-out parody. His outsize vocal impression of a country singer’s twang on “Dead Flowers” would have gotten him punched if he’d tried it in a Bakersfield bar; on a cover of Mississippi Fred McDowell’s version of the gospel standard “You Gotta Move,” his attempts to twist his vowels to sound like a delta blues singer ends up sounding like no actual accent on earth. The Grand Guignol horror show of intersectional stereotypes that comprises the lyrics to “Brown Sugar” never makes it clear whether it’s supposed to be taken as a cutting critique of deep-rooted Southern hypocrisy or a disturbingly glowing airbrushed portrait of old-timey institutionalized sexual exploitation.

Upon its release in April 1971, Sticky Fingers was initially met with bewilderment. The Stones’ more focused exploration of Delta blues and their appropriation of the au courant soul sound of the Muscle Shoals studio (where the album’s recording sessions started) seemed like a logical next step for the band, but their embrace of country music (which was, after all, the sound of the counter-counterculture) and the seemingly contradictory impulses in the way they used those influences perplexed listeners, especially critics, and especially those of a political bent. No less a Stones superfan than pioneering pop writer Ellen Willis—whose mash notes to their music in The New Yorker are among the most heartfelt works of the era’s emerging rock-crit movement—called the record disappointing. She intimated in print that she was among a movement of “erstwhile loyalists” contributing to a “perceptible anti-Stones reaction” at the time. Still, the album sold well, “Brown Sugar” went to No. 1, and the feelings of erstwhile loyalists did little to disrupt the momentum that was taking the band into their second decade of dominance over the rock ’n’ roll scene.

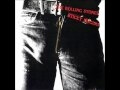

It turns out, though, that Sticky Fingers was a grower (no sleeve-art-based pun intended). After the album’s initial shock faded, it became clear that The Stones had pulled off something significant: The album finished the work that The Flying Burrito Brothers’ Gilded Palace Of Sin and Dylan’s Nashville Skyline (both released two years prior) had begun in terms of reconciling rock and country. Almost as a bonus, it pulled off a Freaky Friday-ish reunion of rock’s black and white parentage by figuring out how to get modern soul and modern country to comfortably coexist on one record.

In the years since, Sticky Fingers has become one of the Stones’ iconic albums, and not just for its notorious cover art. The album sits at a sweet spot partway in between Let It Bleed’s crisp, punchy pop and Exile On Main St.’s gloriously shambolic excesses, and at least half its tracks—“Brown Sugar,” “Bitch,” “Wild Horses,” “Sister Morphine,” and “Dead Flowers”—have entered the upper echelon of the Stones canon. Despite Jagger’s outrageous twang, “Dead Flowers” has turned out to be one of the band’s most significant contributions to country music, a worthy companion to the Bakersfield-inspired outlaw country scene that was starting to pick up at the time and a foundational text for the alt-country movement that would coalesce a couple decades down the line.

One aspect of Sticky Fingers’ legacy that hasn’t been widely discussed is the fact that it seems to have laid down a significant part of the blueprint for Southern rock, which would emerge as a distinctive subgenre and subculture just a couple years after the album’s release. The Allman Brothers are most widely credited with inventing the style, but while the Allmans gave Southern rock its longhaired-bluesman identity and propensity for extended jamming, they don’t seem to have as much to do with the heavy country-fried soul that its biggest acts specialized in. Listen to Lynyrd Skynyrd or The Marshall Tucker Band next to an Allmans record and you can pick up on a certain resemblance. Put them next to the muscular guitar soul of “Sway,” the honky-tonk freakout of “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking,” or the howling ballad “I Got The Blues,” and the similarities are uncanny.

It may be that the Sticky Fingers formula was just The Stones picking up on something that was already in the air–the Muscle Shoals sound was already pretty big, and there were plenty of young musicians on their way up who loved soul music just as much as they loved country. But its similarities to the Southern rock that would follow extend well beyond aesthetics. The first sessions for Sticky Fingers went down just days before The Stones played Altamont, and most of it was recorded after, when much of the counterculture—fed up with the band’s unabashed apolitical egocentrism and capitalist impulses, tipped over the edge by the stabbing of Meredith Hunter—had already started accusing the band of killing off a revolution that had started at Woodstock.

For their part, The Stones seemed just as fed up with the counterculture. The pastoral ballad “Moonlight Mile” and the Santana-esque extended jam on the outro to “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” (which otherwise eerily predicts Skynyrd with its choppy, funked-up guitar riffs) are the album’s only significant concessions to psychedelia, while the baleful junkie howl of “Sister Morphine” couldn’t have been better designed to harsh a buzz. While the hippies struggled to hold together a movement based on peace and love, The Stones countered that “Love / It’s a bitch,” and let the still-fresh memory of Meredith Hunter’s fate suffice to explain how they felt about peace. While Sticky Fingers may have started out as a tribute to the South’s music, in their post-Altamont days (if not before), The Stones found themselves occupying a reactionary headspace that for a bunch of louche British millionaires had a remarkable amount in common with working-class rednecks, and making a sound that would go on to resonate so much with Southern listeners that they’d claim it as their own.