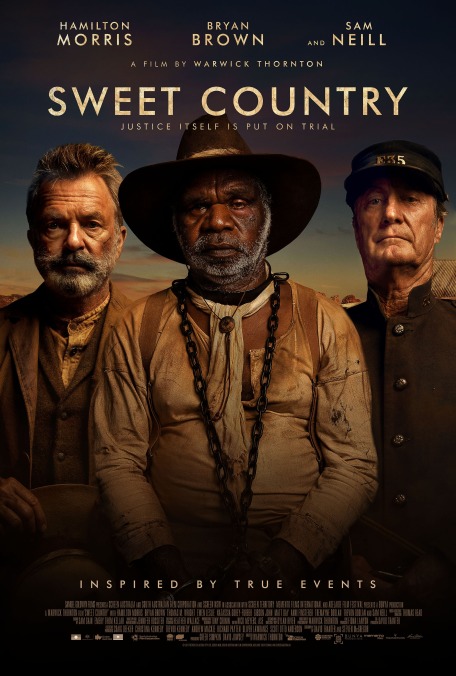

The striking Outback oater Sweet Country views Aussie history through a Western lens

So common you could call it cliché, the asynchronous mid-scene cutaway has become a clear shorthand: When the location changes but the sound doesn’t—transporting the audience someplace new and keeping it locked in the moment—you know you’re seeing a flashback. But that’s not always the case in Warwick Thornton’s quietly enraged Outback oater Sweet Country. More often than not, when the timeline does briefly splinter, it’s to offer a preview of what’s to come, not a glimpse of what already has. The film uses these wispy premonitions for multiple purposes, to misdirect, to entice, to foreshadow; when a character’s introduction is followed by a quick shot of her planted in the dirt, face splattered with blood, we wait on bated breath for the violence lurking ahead. Mostly, however, each blink into the future serves to underscore the fatalism— the sad sense that history may already be written for everyone on screen.

Is it written for Sam Kelly (Hamilton Morris)? An aboriginal stockman working the inhospitable bush of the Northern Territory, Sam is introduced in chains, on trial for murder. It’s 1929, and he’s shot and killed a “whitefella” in self-defense—a drunken, crazed British soldier (Ewen Leslie) who spent his last days alive subjecting every black body within reach to his appetites, his frustrations, his volcanic temper. Much of Sweet Country, which is loosely based on a real horror story of Australian history, depicts the aftermath of the killing, as Sam and his wife, Lizzie (Natassia Gorey Furber), flee into the arid wilderness, an angry posse in hot pursuit. But by opening as it does—out of time, with the wanted party in custody—the film leaves no doubt as to where it’s headed. Sam is a black man who’s killed a white man in the Australia of the 1920s. It would take a miracle of God or justice for his fate to be less than sealed.

With its sprawling desert vistas, violent frontier conflict, and seizure of indigenous lands, the Outback of old isn’t so far removed from the Wild West of American legend and cinema—which is why, of course, there’s a whole subgenre of Aussie Westerns, from Mad Dog Morgan to The Proposition. Thornton, who previously explored aboriginal culture in Samson And Delilah, twists the genre’s tropes into a kind of origin story of a country built on the backs of its original inhabitants. Scarcely a scene passes that doesn’t reflect on a legacy of subjugation—evident in the brutish racism of the “victim,” who forces himself on Lizzie in a scene of quiet and almost casual atrocity, but also in the general treatment of all the aboriginal characters, mocked and abused by the ranchers and the drunken townsfolk of the nearby one-horse hamlet. “They took my country,” laments Archie (Gibson John) to his fellow aboriginal farmhand, the teenage Philomac (brothers Trevon and Tremayne Doolan), whose own mistreatment sets the plot into motion. Indentured servants at best, the two are pitted against each other by their boss, forced to scramble for meager reward.

It’s a revisionist Western through and through, even beyond the move Down Under. The action is sporadic and unexciting, every potential showdown ending as quickly as it began. Sam, laying low in the desert, evades capture not through stirring heroics but basic survival skills; the manhunt is resolved anticlimactically, and its only casualty is “spoiled” immediately, through one of those swift leaps forward in time. There’s not even a score to hum along to, only the lonely whip of the wind. For on-the-nose emphasis, Thornton includes a scene of slack-jawed settlers hooting and hollering along to The Story Of The Kelly Gang, a 1906 Australian silent about that most famous bushranger, Ned Kelly. But he didn’t need the illustration for anyone to recognize the wide chasm separating gung-ho legend from the unromantic truths of history. It’s as clear as the discrepancy between the striking beauty of the Outback and the ugly hearts of its colonial interlopers.

Moving at a meditative crawl instead of a gallop, Sweet Country won’t satisfy anyone’s thirst for old-school gunslinging fun. But it has its own hypnotic mood and flavor: that familiar Ozploitation feel for the nebulous boundary between civilization and the anarchic wild. At the center of a cast of distinctive character actors, the largely unknown Morris looms like a pillar, stonily enduring slings and arrows. If his Sam is the martyr of this story, its witness is his employer: a country preacher played, with a characteristic flicker of soul, by Sam Neill. With growing horror and a shaken faith, he sees what the movie, with its achronological hiccups, is getting at: the terrible foregone conclusion of national identity, a future sculpted by the prejudices and injustices of the past.