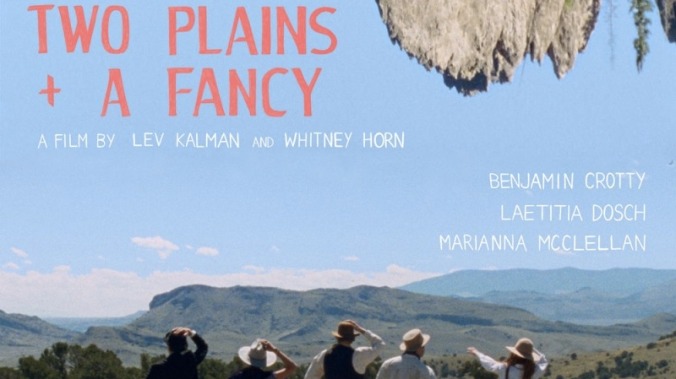

The plot (if it can be called that) concerns three pleasure-seekers who have travelled to Colorado during the silver bust of 1893 to soak in the local hot springs. Milton Tingling (Benjamin Crotty) is a New York City dandy and watercolor artist who holds unusual beliefs about turkeys; Ozanne Le Perrier (Laetitia Dosch) is a French geologist and snob; Alta Mariah Sophronia (Marianna McClellan) is a former confidence woman who used to swindle suckers with sham séances, but has since become a quasi-reformed believer in “sub-natural” (as opposed to “supernatural”) phenomena. In between visits to the springs, they eat canned lobster; take in the mountain scenery; debate the merits of magnetic and mineral healing; encounter invisible time travelers; meet a couple of disillusioned cowpokes named Ken Buns and Cliff Perfecto; and have sex with ghosts.

This gives Two Plains & A Fancy the rough outline of a shaggy-dog comic odyssey, though Horn and Kalman put everything in scare quotes, the locations often represented by signs that look like they were painted minutes before the camera rolled. Their filmmaking is unpolished, and, in a few stretches, downright aggravating. One can see it as being part of a tradition of experiments in Western play-acting that goes back to Andy Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys, and a curious sub-genre of pokey, pseudo-paranoid 16mm micro-indies with significant postmodern literary influences (mostly Thomas Pynchon) that includes Alex Ross Perry’s Impolex and Bingham Bryant and Kyle Molzan’s For The Plasma; what these films all have in common is that they seem to originate in New York (where Horn and Kalman met before relocating to the West Coast) and approach the great outdoors as a world of make-believe. (Though in Warhol’s case, said make-believe comes loaded with sexual violence.) Nothing here is meant to seem real—apart, that is, from the directors’ appreciation for rugged landforms, which appears heartfelt.

But then, what’s the point? Comedy is complicated and contextual, and the line between intentional and unintentional humor becomes confusing when the former mimics the latter. The lamest version of this proffers the ironic intention as the whole joke—i.e., it’s bad on purpose. (In which case: Congratulations, you’ve made a bad film.) Two Plains & A Fancy rises above its shakiness largely on the strength of Horn and Kalman’s humor: the non sequiturs, the well-timed throwaway lines, the simple-but-effective visual gags. As in L For Leisure, their writing sometimes betrays the influence of Whit Stillman, the master of the dry burn. “You’re a dandy, but you’re not really a wit, are you?” says Alta Mariah to Milton. “I mean, when you hear about dandies, they’re always going around saying witty, clever things and you don’t really do that.”

As Milton, the wuss who insists there’s a paisley scarf and a waistcoat for every occasion, Crotty gets the funniest dialogue—though it’s difficult to explain why lines like “I’m dying of scrapes” and “Excuse me, horses” sound hilarious without the visual context. With McClellan’s Alta Mariah acting as his scene partner in American self-delusion, Dosch’s Ozanne is often left to play the part of the culture-clash foil and to speak at length on the subjects of anthropology and glacial erosion—suggesting that maybe, just maybe, there’s something out there that the filmmakers believe in sincerely.