For Levinson, the project became immediately personal upon reading Justine Juel Gillmer’s script and remembering a childhood visit from an uncle who, like Haft, had survived the concentration camps. “Every night he tossed and turned and screamed in horror,” Levinson has said. “I have always been curious about exploring the idea that when someone experiences something like a war or a concentration camp, they don’t just leave the experience and get on with their lives.”

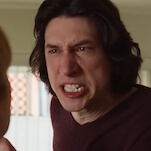

Ben Foster: Thank you for the kind words, Barry. When I auditioned for him, yeah, it was my first film. And I was so intimidated and afraid of being bad in Barry Levinson’s movie, you know? [Levinson laughs.] We had a VHS of Diner and Tin Men and Avalon at home. I mean, it’s part of the fabric of our family’s viewing. So to be brought on and into that Baltimore series was an inconceivable anxiety. [Laughs.] And what I learned from Barry is something that I’ve taken with me to every film, which is: Try this, try that. There’s a deep musicality to Barry’s words and his rhythms, and also how he approaches the scene. He supports controlled improv—“Let’s see what happens.” So I hope we’ve evolved, but it’s definitely true that Barry has been with me from the beginning. It’s been a joy to come back and work together.

AVC: Ben, were there moments of déjà vu filming this with Barry?

BF: It just felt incredibly comfortable. I mean, considering the material isn’t the most comfortable. But in a working relationship, yes, he’s always creating, he’s always writing new scenes. He’s after it. And whatever that it is, it might show up on the day. And it makes it incredibly free and present. Everyone feels very free and present on set. And that’s due to Barry’s approach.

AVC: Going off of that, what are your approaches to improvisation in the creative process? And in this movie, what scenes or moments were improvised?

BL: I’ll point out one, but I think in general, you’re always saying, “Is there something else in the scene?” Sometimes, no, we can’t add to it. And sometimes you say, “Well, what about what about this or what about that?” I’ll just give you one example. Very late in the movie, there’s a scene between Harry and his wife [Miriam Wofsoniker, played by Vicky Krieps]. And the scene ends where he basically explains one of the things he’s never talked about, a rather horrific moment. And he finishes and his wife goes over, and she ultimately hugs him. And I said to Vicky just before this scene began, “When he reveals that and it’s one of the things he’s never, ever mentioned, it’s the guilt that he truly feels—and what happens if you don’t get up and go over? If you don’t hug him?” And she said, “Really? Do we talk to Ben?” I said, “No, no, no, just do it and let’s see what he does. What happens if you don’t comfort him?”

So he did that scene and was wonderful in this particular take. And she didn’t get up. And that created a whole other dynamic that I think was rather revealing and important to the overall piece. And Ben immediately, his response, when she did not provide that comfort, added a dimension that made you go, “Wow, this is interesting, this behavior.” And so that’s only by thinking, “Was there something else here?” You never want to feel like you walk away from a scene and you’ve left something that the audience could be engaged by, another little insight into a moment here. That’s what you go for. And Ben is, I think, alive enough and connected to the character that he was able to run with it. And I think the scene became very effective.

BF: I wasn’t prepared for it, or at least wasn’t privy to the private chat he had with Vicky. Really, it’s a short scene, and I think the extent of it on the page was, “You don’t know the worst part of me,” and turn his back to face the sink, and she’s going to get up and give me, give Harry, a hug. But it wasn’t just that she didn’t get up and give me a hug; I believe she started antagonizing Harry and saying, essentially, “What is it? What is it?” And what was supposed to be a soft, gentle moment, I started feeling this aggression. You know, don’t poke the bear. And from that, I just started telling the story—which we had already shot, a scene in the ring, but it wasn’t written. But because we had already shot it, I just started talking about my friend… So it was a surprise for everybody.

AVC: That’s a great example of how a story changes from page to screen. What were your first impressions upon reading Justine Juel Gillmer’s script? And what were your expectations for how this process would go?

BL: One, I thought it was an interesting story, obviously. And secondly, I related it to the experience of [my uncle Simcha] in my room and the nightmares he was having. And that [memory] came up right away. It informed me, in a way. Having read the script, some things just started to come out, because it was rich material to play with.

And then when Ben came aboard and has that ability to say, “Let’s see what happens,” then you just try to fill it in. I mean, that’s all you were trying to do: fill it in, provide something to the audience. I always think of it like they’re almost leaning forward in their chair because they don’t want to miss something. You’re hopefully trying to have that connection between what’s going on, what you’ve created, and what the audience is responding to. So it all begins with the material. I mean, this man is basically walking through life as a survivor, but he hasn’t really survived yet. So what does that mean? How do we play that? It’s not just in the words, it’s in the visual on the screen.

That was, I think, the excitement of this particular journey… The script lays out the piece and then you just have to be able to refine what’s going on on the screen. A lot of it has to do with the actors. Because we’re watching them, and especially in this, a lot of this movie is what isn’t said. So that in a sense is really on the shoulders of the actors. Ben is moving through this and we have to be engaged enough to know, What else do I not know? Something else is going on, and that’s part of it. I don’t know that I could explain it any better.

AVC: Ben, it seemed like there was a lot on your shoulders, from all that subtext to losing and gaining 62 pounds. How did you move on from that vulnerability, from a role that involves reenacting trauma?

BF: Well, we’ve all experienced different levels of trauma, every human being. What’s the Hank Williams quote? “We’ll never get out of this [world] alive?” [Levinson laughs.] And the trade of our job as an actor is to get as close to the role as you can so you don’t have to think about it. Losing the 62 was a choice and a privilege for me because I got to make that decision; people who lose that kind of weight often don’t have the choice. So it was a visceral experience. It’s a sensual job. It has to be in the body—for me, at least, it has to be in the body so I can turn my brain off.

AVC: The Survivor is being released on Holocaust Remembrance Day. Are there other books or works of art that would you recommend for audiences looking to find out more about the Holocaust?

BF: It’s important to take pause and reflect, in order to better understand what’s going on today. I’d say the one that I’ve returned to over the years is Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search For Meaning. It’s a slim volume but the wisdom therein—it cleans the glass for me. I can see a little bit clearer.

BL: And unfortunately—if you ever see the numbers, I believe, I may not be accurate—like 40 percent of high school students don’t even know about the Holocaust. It’s not that you have to just remember this one thing. It’s like, how many things do we just forget and let go? I mean, what takes place as we move through life isn’t based on just the future. It’s based on the past. And if we don’t understand the past, then, you know, where are we?