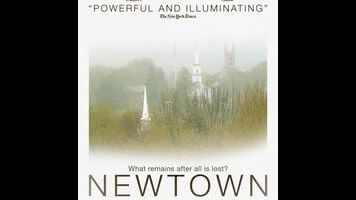

There would seem to be no words to describe the unspeakable horror of what happened at Sandy Hook Elementary School, where a deranged gunman took the lives of 26 people, most of them children. And yet the men and women featured in Newtown do find words. They speak soberly, candidly, and even philosophically about how they’ve coped with the loss of their kids and the violence that tore their Connecticut community apart. Kim Snyder’s wrenching documentary consists largely of interviews with townspeople, including parents of the victims, surviving siblings, educators, first responders, religious leaders, and ER surgeons—basically anyone directly affected by the tragedy. Relying heavily on talking heads is usually the mark of a documentary without much imagination, but what more should a movie on this subject do than create a space for these people to discuss their pain and trauma?

Most of the interviews in Newtown were conducted nearly two years after the terrible events of December 14, 2012, and that relative distance makes a difference. Besides mitigating the potential for sensationalism or tabloid exploitation, respectfully waiting a while allowed Snyder to capture more than the shock and despair of the immediate aftermath. Her interview subjects—including the three bereaved parents who give her full access to their homes, families, and memories—have had time to reflect. Grief has reshaped their lives completely; it’s also turned each of them into self-aware experts on their own complicated, shifting emotional states.

“I still dread that, every day I live, I’m one day further from my life with Daniel,” confesses Mark Barden, who’s especially frank and eloquent about his struggle to move on, discussing how his dreams have become variations on the attack and how his mind envisions it went down. Mark feels an intense need to know exactly what his son experienced in his final moments, no matter how painful that information would be. He’s not alone: Nicole Hockley, who lived across the street from the shooter, has gone as far as contacting parents of her deceased son’s classmates, hoping to eventually feel ready to hear their stories about December 14. For nearly everyone who was there—and many who weren’t—life can now be divided into two distinct eras: before and after. Newtown weaves their separate testimonials into a tapestry, attempting to convey what it looks like when a whole community mourns in unison.

Not surprisingly, the shooting at Sandy Hook has made what one news report calls “accidental activists” out of several of the parents, who redirect their anger and sorrow—and lend their experiences—to the uphill battle for gun-control legislation. Newtown doesn’t adopt that agenda, or any other one, really; it’s a portrait of a town struggling to heal, not a polemic. All the same, it’s difficult to watch David Wheeler, another of the grieving fathers, testify in front of Congress with clear-eyed conviction and not see the logic of his assertion that our right to machine guns does not supersede the safety of our kids. (This plea fell on mostly deaf ears—the Senate rejected stricter background checks.) Likewise, Snyder lays out the details of the shooter’s actions—his access to the firearm, the ease with which he entered the building—in a way that makes it clear how vulnerable the laws leave us. In other words, what happened at Sandy Hook could happen at just about any school, so long as guns remain so easily obtained.

From a filmmaking standpoint, Newtown is neither adventurous nor unconventional. It doesn’t need to be; no documentary this emotionally direct, this emotionally draining, requires bells and whistles. Early on, one of the state troopers who intervened recalls witnessing the scene of the crime, and insists that this is not a description that needs to be shared—that people need to understand what happened there, but not the awful specifics. Some of the parents obviously disagree, but Newtown seems to support his philosophy on the matter; it doesn’t attempt anything like a comprehensive timeline of events or a chronological account of the day. (Notably, Snyder has cited as an influence Atom Egoyan’s masterful, fictional The Sweet Hereafter, which neither begins nor ends with the school-bus accident that drives its plot.) The structure is more intuitive, organizing observations around an emotional logic. “I don’t want closure,” Barden insists toward the end, and Newtown doesn’t provide it. The film leaves its subjects where it found them: caught in a morass of mourning, searching for a path forward, finding strength in numbers.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.