Talking Heads released their first three albums in the ’70s, but the band belonged to the ’80s. With one foot in art-rock experimentation and the other in new-wave pop, it built the platform for its own success, helping make weirdness acceptable to Middle America—or at least palatable enough to turn 1983’s “Burning Down The House” into a top-10 hit, and the resultant album, Speaking In Tongues, into the band’s first platinum-seller.

By 1987, though, weirdness had gone mainstream. Much in the way alternative rock became domesticated in the ’90s (and indie rock a decade later), new wave—partly a marketing gimmick to begin with—had grown to infiltrate much of the music establishment. Huge acts of the ’70s, the ones Talking Heads had meant to replace, now sounded like contemporaries. 1986 saw the release of discs like Paul Simon’s Graceland, which steeped itself in the same multicultural sounds that Talking Heads had been dabbling in for years—and that frontman David Byrne would soon dive more deeply into. Even bands like Rush and Genesis had ditched the grand spectacle of the ’70s and by 1987 were making quirky, jerky, minimalist rock. And then there were two of Talking Heads’ kindred spirits: The Smiths, who had just finished a string of era-defining albums with the majestic Strangeways Here We Come, and R.E.M., whose hit record Document gave the group its first taste of superstardom.

As Morrissey embarked on a lucrative solo career and R.E.M. embraced its hard-won success, Talking Heads began to inch away from the spotlight. Jonathan Demme’s 1984 excellent concert film Stop Making Sense had given the band visibility, but it had also turned Byrne into an icon—if not a cartoon. But the public at large needed another token weirdo, and Byrne fell into the role. Speaking In Tongues was chased by another platinum album, Little Creatures, which highlighted the group’s escalating sympathy for more easygoing, crowd-pleasing pop.

Something happened, though, with Talking Heads’ next full-length, 1986’s True Stories. Released in conjunction with the Byrne film of the same name, it’s more scattered and restless—and in that perverse way, it’s more focused on the fundamentals that made Talking Heads what they were in the first place. The movie was a crisis of faith, a warped love letter to America that wasn’t actually that warped at all. Byrne, tasting the backwash of all the irony he’d infused into the decade, was clearing his throat—and turning into a sentimentalist.

Released in 1988, Naked is Talking Heads’ final album. Compared to the group’s early releases, it’s more of a whisper than a roar. Which is one reason why it’s so gripping. Supple and subdued, it lacks the urgency, stridency, and angularity of early Talking Heads. It’s also wonderfully lush. While so many bands had begun, belatedly, to take their cue from Talking Heads’ formative sparseness, Byrne and crew were reversing course, working in a widening number of instruments and guest musicians—including The Smiths’ former guitarist, Johnny Marr, whose luxuriant jangle adds yet another layer of melody and texture to Naked’s gorgeous lead single, “(Nothing But) Flowers.”

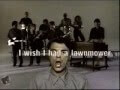

The broad, organic sonic palette of “Flowers” isn’t the song’s only break from Talking Heads' past. It reflects Byrne’s encroaching sense of sincerity. After outlining a paradoxically dystopian scenario where the modernized world succumbs to nature and becomes a new Garden of Eden, he wistfully pines for the way things were. Or rather, are. “There was a shopping mall, now it’s all covered with flowers,” he sings with a waver in his voice, a human glitch that belies the robotic chirp he once deployed. “If this is paradise, I wish I had a lawnmower.” It’s as if Byrne intended the song as both a reiteration and a rebuttal of Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi.” As Mitchell sings in her back-to-nature anthem, the forces of progress have “paved paradise and put up a parking lot.” But in the future, Byrne sings, we might look back at the 20th century and observe, “Once there were parking lots / Now it’s a peaceful oasis.” Only that oasis might in some ways be more desolate than chain restaurants and cracked asphalt, leaving Byrne to long for all “the honky-tonks, Dairy Queens, and 7-Elevens.”

In the ’80s, suburbia was demonized. Nonconformity was a catchphrase, and everyone from Rush to The Descendents railed against the oppression of white-picket-fence America. Hating the suburbs was cool. Byrne couldn’t have cared less. On “Flowers,” he waxes environmentally while recalling the nostalgia for a tacky, vanishing America he first explored in True Stories. There’s still that twinge of irony in his voice, but not as much—and even then, he sounds as if he’s trying to purge it from his system. As he confesses in his quasi-memoir How Music Works, “I realized then that it was possible to mix ironic humor with sincerity in performance. Seeming opposites could coexist. Keeping these two in balance was a bit of a tightrope act, but it could be done.”

Accordingly, the most poignant verse of “Flowers” crystallizes the whole song, not to mention Byrne’s conflicted mindset during the twilight of the ’80s: “Years ago I was an angry young man / I’d pretend that I was a billboard / Standing tall by the side of the road / I fell in love with a beautiful highway.” Surrounded by the subtle patter of polyrhythms and the pulse of post-industrial atrophy, he’s Adam longing for the apple. Soon after Naked’s release, he’d be hitting the highway he sings about in “Flowers,” leaving the band and decade that defined him—as well as confined him—in the rearview mirror.

Technically speaking, “Flowers” isn’t Talking Heads’ last single. Two more, “Sax And Violins” and “Lifetime Piling Up,” emerged in the early ’90s, but they were tied to a soundtrack and an anthology, respectively. By that time Talking Heads was treading water, soon to fizzle out with the announcement of its breakup in December 1991—just as Nevermind, unleashed in September, was conquering the world. For all intents and purposes, though, Talking Heads gave up the ghost in 1988, when “Flowers” laid a funeral bouquet on suburbia, the band itself, and the ’80s along with it.