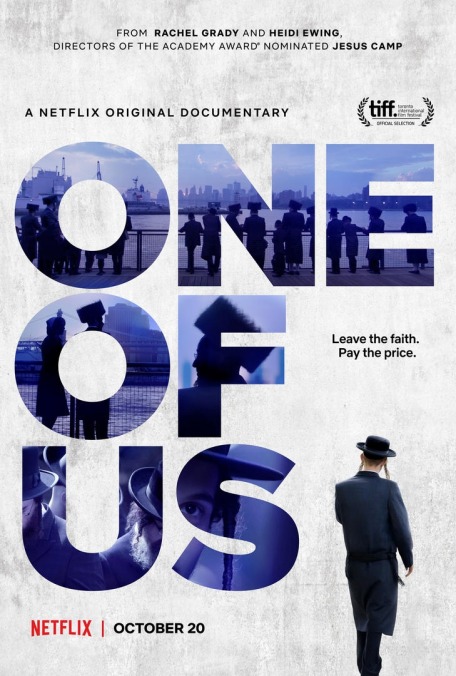

The team behind Jesus Camp documents harrowing escapes from Hasidic Judaism in One Of Us

There’s no shortage of documentaries about the religious fringe, and they run the gamut from highlighting quirks to condemning criminal behavior. One Of Us spotlights a group that hasn’t faced the scrutiny of film crews quite so often as the likes of Scientologists or even Christian conservatives: Hasidic Jews. Rather than attempt an overarching portrait of the sheltered, rigid group, filmmakers Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady (who directed Jesus Camp, so they’re no strangers to this type of story) follow three members who commit the unforgivable sin of stepping away from the religion. As with the Amish, who’ve been more exhaustively documented, leaving this ultra-Orthodox life doesn’t mean that you simply don’t worship anymore: You leave everything behind, including—in this film’s most compelling story—your children.

That’s Etty—no last name, and no face shown for most of One Of Us—whose story begins the film with a 911 call. Having decided to leave her abusive husband after years of what was essentially an arranged marriage, she’s subject to harassment by the rest of her community. They’ve been taught for their entire lives to shun the outside: Their education, interactions, and relationships are all tightly controlled. They can’t go to public libraries. They rarely use computers. They respect their elders no matter what those elders might do. Women are fully subjugated to their husbands, and expected to provide baby after baby after baby, with little or no thought given to their own happiness. When she finally decides she’s had enough, Etty understands that leaving her husband and religion will also likely mean leaving her seven children. She doesn’t have the money for a lawyer, whereas the community will spend whatever it takes to keep her children from the scariest fate of all, becoming “modern.”

One Of Us spends frustratingly little time, however, exploring the motives behind the Hasidim’s cloistered existence, raising but brushing quickly past the idea that these particular Jews—mostly living in Brooklyn—are so scarred by the memory of the Holocaust that they believe community is the only thing keeping them safe. (It brushes even more quickly past the idea that they value children so greatly because they’re essentially trying to repopulate.) The film does little to explain the history behind the dynamic between their men and women, which is based, it seems, at least partly on a blinding fear of lust. Instead, it focuses more on the fallout: the mental scars, the logistical problems of leaving a community that has been your entire support system for your entire life, the total loss of family. It’s fascinating, but it feels incomplete.

The other stories are less harrowing but also less compelling. A young man named Luzer left Hasidic Judaism to pursue a career in Hollywood, knowing full well that he’d probably never see his wife or two children again. After telling his mother on the phone that he’d gotten a divorce, she hung up, and they didn’t speak again for seven years. He seems lonely but relatively well adjusted. Ari, on the other hand, has both horrific and funny stories to tell. He discovered Google and Wikipedia, which served as his apple of knowledge. (“Wikipedia was a gift from God,” he says, before a long pull from his vape contraption.) He longs for the community he left, but there’s no way he can trust it after revealing that he was sexually assaulted by an elder—and no one would believe a child over an elder. He has a conversation with a different elder later, after he’s made what seems like an irrevocable personal realization: “Either there is a God and He’s evil, or there is no God and that’s why things are the way they are.”

But those types of moments aren’t as devastating as they might be if One Of Us had laid a stronger foundation about Hasidic Judaism itself. There’s some background, but what might be the most fascinating part of these stories—the why—is sidelined in favor of more intimate, close-up portraits. Which isn’t to say that One Of Us isn’t itself fascinating, but it’s almost like an intermediate-level study without the prerequisite background.