The Thermals’ best album is relevant again, but that’s not what makes it so great

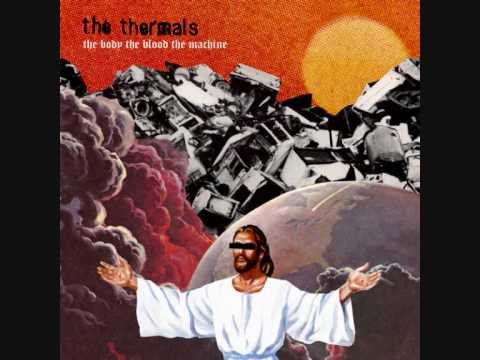

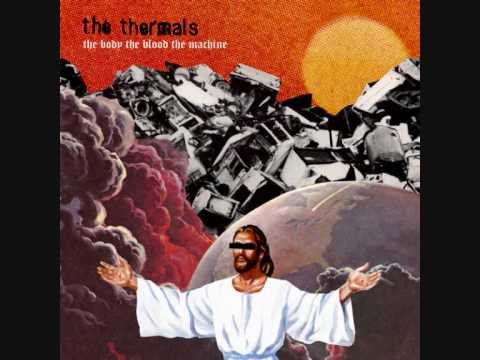

When The A.V. Club put together an Inventory of George W. Bush-era political works that still hold up, we couldn’t have known just how applicable they would be in a Trump presidency. Likewise, when The Thermals released the career-best album The Body, The Blood, The Machine in 2006, they weren’t banking on their unapologetic skewering of the former president’s war-focused “strategery” and the religious right being so painfully resonant on its 10-year anniversary.

But when Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election, TBTBTM, like some of the other works we recognized in that 2017 Inventory, sounded prescient. And when frontman and founder Hutch Harris wrote an open letter to Trump supporters for Talkhouse in the immediate aftermath, the connection solidified. The third Thermals album is a masterful concept work, set in an apocalyptic near-future that puts power, oil, and a Christian God above everything else. Every track is blistering in its own way, and helps tell the story of a fascist regime intent on establishing new borders, demonizing those who don’t fit the mold or fall in line, and sending those who do off to war. It’s 36 minutes of sound and fury, urgency and humor, criticism and love, all set to some of indie rock’s catchiest hooks.

The album’s already gotten a loose follow-up—2009’s Now We Can See, which is told from the perspective of the dead—but its renewed relevance could power another round of touring. That is, if the Thermals hadn’t officially and amiably called it quits last month. But Harris and his longtime bandmate Kathy Foster, as well as drummer Westin Glass, derive little satisfaction from seeing fans draw parallels from the album’s bleak, fictional future to our bleak, all-too-real present. As Harris says, “Obviously, we’re so proud of the record. We feel like it’s the best thing we ever did. Most of our fans feel like it’s the best thing we ever did, but for it to be coming true—it’s not a positive thing.”

In some ways, focusing on the album’s political themes does it a disservice—TBTBTM remains disturbingly pertinent, yes, but it’s also just one of the best and tightest pop-punk records ever. During their 16-year run, The Thermals carved out a post-punk niche in the indie-rock scene, full of songs that used bursts of energy as a backbeat. They kicked off their career with the very lo-fi More Parts Per Million, an album recorded and performed entirely by Harris. His vocals are at their snottiest, his lyrics at their snidest, and every barely-two-minute track threatens to destroy Harris’ kitchen, which served as his recording studio at the time. More Parts Per Million also has some commentary, which, on “No Culture Icons,” seems directed at Harris himself, but The Thermals would need one more album before hitting their peak.

The band’s sound became more polished over time, thanks in part to collaborators like Death Cab for Cutie’s Chris Walla, who produced their sophomore album, Fuckin’ A (which is underrated by my standards, but not by Harris’), and Fugazi’s Brendan Canty, who handled production for TBTBTM. This progression continued on their four subsequent albums, even as the group stuck to their bare-bones arrangements and enervating live performances. Walla and Canty might have found a way to clean up Harris’ wailing on the mic and guitar, but the energy remained barely contained. Every Thermals song sounds like the first and last Thermals song, because the band gives its absolute all on each and every one. I saw them play at the now-defunct Ultra Lounge in August 2013, and remember seeing Glass take off his T-shirt and wring out all the sweat on the Chicago sidewalk, which is almost demure compared to Harris’ habit early on of stripping down to his underwear.

The band has been dinged for not moving far enough beyond a sound first established in 2003, but in 2006, they could have easily released another collection of wall-shaking punk-pop songs to acclaim. Harris says he and Foster didn’t give much thought to what kind of album they’d make before making it; they came up with TBTBTM’s concept—“a fantasy, of like, ‘Well, things aren’t the worst right now, but how bad could they get?’”—as they were writing it. They’re both recovering Catholics, which is why there’s so much religious allegory in the lyrics, from Noah’s calling in “Here’s Your Future” to the come-to-Jesus moment in “Returning To The Fold.” The disillusionment with religion heard on “I Might Need You To Kill” turns into renunciation on “Back To The Sea,” which contrasts Biblical allusions with primordial imagery.

As cathartic as it is for Harris to basically say “fuck this” and return to the water that birthed our species—a nod to evolution that probably pissed off his former fellow congregants—the sense of surrender on “Back To The Sea” is chilling, especially as the track is followed by the last gasp of the ruling class on “Power Doesn’t Run On Nothing,” and the fallout of “I Hold The Sound.” But let’s back up a bit and revisit the superb album opener that is “Here’s Your Future.” Harris says it’s his favorite song off what he and fans agree is the band’s best album. “It goes so many different places, and it changes a lot for such a short song. Kathy and I didn’t demo a ton for the record; a lot of what’s on that record just kind of came out while we were in the studio with Brendan Canty. A lot of great stuff we came up with on the spot, so that when we mixed, we were kind of surprised and pleased at what had happened. And ‘Here’s Your Future’ was definitely a song like that.” It quickly sets up the album’s premise. The track’s god is a vengeful one, who casually lays out his plans to decimate the population (“Remember that no one can breathe underwater”). Bush the younger was only slightly more formal when he started two wars, but his motivation’s the same; he once said, “God told me to end the tyranny in Iraq.”

Harris sounds much more somber on “I Might Need You To Kill,” a song which, like the mid-album “Test Pattern,” is about the insidiousness of indoctrination: “They’ll pound you with the love of Jesus / They follow.” The song’s target is the religious right, which has had a dismayingly powerful influence on elections. Trump’s embraced that evangelical base, just as Dubya did, even if they both fail to live up to that bloc’s ideals, their anti-Muslim policies aside. Then, with that foundation laid, TBTBTM ratchets up the paranoia and punishment on “An Ear For Baby,” which is full of Nazi allusions, the song’s “Work is freedom” line paraphrasing the “Work sets you free” inscription at concentration camps. Harris’ vocals remain at 10 throughout, the volume suiting both the soldiers’ commands to “dig the ditches deep” because we “need a new border,” and the captives’ desperation, whose prayers aren’t likely to reach God. As disturbing as its imagery is, Harris explains that he was stopping to think of the children: “The idea that I had when I was writing it, is that someone thought to be taking care of the children in the midst of all this apocalyptic chaos.”

From there, the album moves into “dancing on our own graves” mode, with songs full of driving guitar riffs that make it impossible to hold still, even if it means giving away your location. The Lot-inspired “A Pillar Of Salt” is a two-and-a-half-minute encapsulation of everything Thermals, with its rebellious streak and pounding bass. It also introduces the couple we’ll follow for the rest of the album, the one that’s, per The Thermals’ own description, fleeing a fascist regime. They don’t want to have to “deny [their] dirty bodies,” so they “stick to the ground” on their way to Canada, the ever-popular destination for dissidents.

The deceptively cheerful “Returning To The Fold” sounds like another surrender, complete with Orwellian references: “I forgot I needed God like a big brother.” But though it’s slower than the rest of the TBTBTM songs, the meditative “Test Pattern” fits perfectly into the overall theme. It’s equal parts recruitment ad and love song, comparing the daunting prospect of a new relationship with that of a new religion. Along with “St. Rosa And The Swallows,” it offers respite to the listener and the album’s travelers. These rests were thoughtfully constructed, Harris says: “We didn’t want the record to be all cold and political and dark and scary. Kathy said, ‘We need a couple love songs,’ so there are a few on the record to kind of ground the record in just basic human emotions, in love, while still keeping the very religious, Catholic themes.”

Together, “Test Pattern” and “St. Rosa” represent the bread and roses that all revolutionaries seek, but what little hope they offer is quickly destroyed by the remaining three tracks. After flirting with self-destruction on “Back To The Sea,” TBTBTM hands over the stage to moral dictatorship on “Power Doesn’t Run On Nothing.” If “A Pillar Of Salt” captures the essence of The Thermals, then “Power” represents their peak. Harris’ lyrics are fiery and evocative—“They’ll give us what we’re asking for / Cuz God is with us, and our god’s the richest”—and his voice pained, furious, and boastful all at once. It’s the longest song on the album, and a distillation of its themes. I’m a big fan of Now We Can See, which picks up the through-line of TBTBTM, most notably with “When We Were Alive” (which Harris says was the first song he and Foster wrote for that album). And the Thermals released several more solid albums after The Body, The Blood, The Machine, but “Power Doesn’t Run On Nothing” is the apex of what became the band’s standard-bearer.

On the album closer, “I Hold The Sound,” there’s no hope left and little comfort. “The sun is cold,” Harris sings before chanting, “The world is over.” He and Foster envisioned the end of humanity, which they looked back on poignantly and wryly throughout Now We Can See. A cataclysmic event is followed by another one, symbolized by a long stretch of screeching guitar. That’s the way the world ends—with a bang, a whimper, and a fuck-ton of distortion.

It wasn’t the end of the Thermals, who released four more albums and played together for 12 more years. But the fact that the band hit its high-water mark after just two albums was both a blessing and a curse. They learned what they were capable of, and carried that potency and cohesion into Now We Can See and We Disappear, the latter a rumination on technology and the distance it affords or thrusts upon us. Though no other concept album worked quite as well as TBTBTM, every outing thereafter had a framework, including Personal Life, which is perhaps the most dubious of The Thermals’ efforts, but still has bright spots. But as Harris told Noisey, knowing the band had already released its best album was a factor in its breakup. The Thermals might not have had Radiohead’s artistry or Propagandi’s political-punk bona fides, but The Body, The Blood, The Machine’s cohesiveness puts it on par with their respective Bush-era protest works. But, prescience aside, the album is just as worthy of revisiting by longtime fans as it is an introduction to newcomers who just want to hear some great musical storytelling.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.