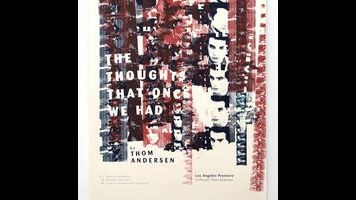

The Thoughts That Once We Had lacks the character of Los Angeles Plays Itself

Part disorganized valentine to the movies, part advanced film-studies lecture, The Thoughts That Once We Had seems destined to disappoint fans of the talented artist who created it. That would be endearingly cranky California essay filmmaker Thom Andersen, whose claim to (relative) fame is Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003), a spiky three-hour meditation on the various ways L.A. has been used and abused on screen. Andersen built his case for the city using a couple hundred unlicensed movie clips, which is why it took years for the film to become available on DVD/Blu-ray. His new project is similarly rich with borrowed cinematic footage, but it loses the snarky voice-over narration, strongly expressed opinions, and general sense of overarching purpose that characterized its predecessor. What the film really lacks, though, is an intended audience—an idea of whom, exactly, it’s trying to reach.

The film announces itself, from the very start, as “a personal history of cinema, partially inspired by Gilles Deleuze.” That personal part is a kind of organizational blank check for Andersen, giving him serious carte blanche to free-associate. Although he begins in the silent era, at roughly the beginning of his history lesson, the director is soon skipping across the decades, identifying rhymes and common aesthetic tropes almost at random. One bewildering daisy chain of connection links Norman Mailer talking about the World Trade Center to Hank Ballard talking about “The Twist” to Charlie Chaplin to Wim Wenders’ The American Friend to the dramatic finale of Errol Morris’ The Thin Blue Line. Those who can’t follow the train of logic won’t get any help identifying the stations: Whereas Andersen named every film excerpted in Los Angeles Plays Itself, to help point viewers in the direction of something they’re intrigued by, The Thoughts That Once We Had doesn’t accredit its clips—a choice that feels oddly exclusive, as though he were speaking only to those with his exact cinematic memory bank.

There is an organizing principle here, and it’s Deleuze, a French philosopher who created a dense taxonomy of filmic language with his 1983 tome Cinema 1: The Movement Image. When not simply riffing on a century of motion pictures, Andersen tackles the theories of this revered academic—for example, using the separate comedy stylings of Harry Langdon, Laurel and Hardy, and the Marx Brothers to demonstrate how Deleuze divides cinema into three basic kinds of images (affection, perception, and action). Except Andersen makes no real effort to explain these concepts, just to illustrate them, which again narrows the scope of his conversation and audience. Instead, he refashions quotes from Deleuze (“The action-image is the relation between determinate milieus and modes of behavior”) into intertitles, which creates the impression of a loose structure. It’s a bit like watching a seminar by a professor who’s misplaced a few of his slides.

A history of cinema is also a history of the 20th century, and Andersen breaks up his montage of favorite shots and scenes (a brief tribute to Marlon Brando, Debra Paget dancing with a cobra) with somber transmissions from the frontlines of American foreign policy, including footage of World War II, the Korean War, and Vietnam. Jean-Luc Godard, who gets name-checked a few times throughout, did something similar with his massively ambitious video project Histoire(s) Du Cinéma. The Thoughts That Once We Had owes a clear debt of influence to that seminal essay film, but Andersen lacks Godard’s gift for kaleidoscopic expression; whereas the latter made an era-jumping epic that could function on its own dazzling formal terms, the former’s drier, straighter approach rewards only those who can keep up.

Andersen has impeccable taste in movies, that much is clear. No world-cinema overview that nods to both the glorious opening montage of Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour and the equally glorious opening shot of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Millennium Mambo is going to be a chore to sit through. At its best, The Thoughts That Once We Had functions like a kind of film-buff mixtape, queuing up one magic moment after another. But the quasi-academic aims of the project mute Andersen’s passion; the director must have felt he needed a respectable framework for his cinephilia, but the personal component often seems directly at odds with the Deleuze component. What’s most missed is the direct address of Andersen’s own musings: Though technically read by Encke King, the narration in Los Angeles Plays Itself created the sensation of having a contentious, engrossing conversation with the world’s orneriest film lover—a guy who’d bombard you with his opinions but also impart a lifetime’s worth of knowledge and enthusiasm. The Thoughts That Once We Had doesn’t impart nearly enough. It’s a communication breakdown.