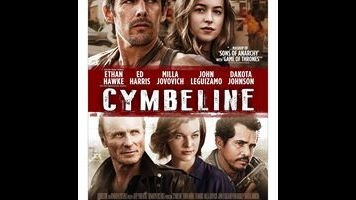

In 2000, writer-director Michael Almereyda took on the best of William Shakespeare, transposing the seminal tragedy Hamlet to modern-day Manhattan and the world of corporate cutthroats. (Ethan Hawke’s moody young prince declaiming the “To be or not to be…” speech in a Blockbuster video aisle was just one of the film’s many inspired re-stagings.) Fifteen years later, Almereyda tackles one of the Bard’s lesser-regarded later works, the plot-heavy tragicomedy Cymbeline, and again unearths untold depths.

This is another modernized telling: The British king Cymbeline (Ed Harris) is now the drug-running leader of the Briton motorcycle club in the New York State suburb of Rome. He’s at war with the local police force, led by Caius Lucius (Vondie Curtis-Hall). But the real challenges are closer to home, in the form of a treacherous Queen (Milla Jovovich) plotting some literally poisonous schemes and a daughter, Imogen (Fifty Shades Of Grey’s Dakota Johnson), in love with peasant skateboarder Posthumus (Penn Badgley).

That would be enough for almost any tale of star-crossed love, death, and revenge. But there’s also a spoiled prince, Cloten (Anton Yelchin), with his own designs on Imogen; a servant, Pisanio (John Leguizamo), whose loyalties are in flux; a treacherous character named Iachimo (Ethan Hawke) who makes a bet with Posthumus that he can seduce the virginal Imogen; and a banished lord, Belarius (Delroy Lindo), raising two of the king’s kidnapped sons (Spencer Treat Clark and Harley Ware) as his own.

It’s easy to understand why Lionsgate wanted to change the title of the film to Anarchy (as in Sons Of…) so as to better capitalize on the film’s seemingly overstuffed parallels with FX’s entertainingly soapy biker series (itself a loose riff on Hamlet). Almereyda’s aims are much different, of course—light and loose as compared to Sons’ frequent self-seriousness. And he is never cowed by Shakespeare’s own status as the greatest of authors, nor by the insistence of some scholars that Cymbeline is little more than Bill S.’s greatest hits, with its reliance on mistaken identities, toxic potions, and cross-dressing disguise. Almereyda instead treats the swirls of plot, characters, and incidents (even the iambic text itself) as sublime absurdities, things to be tossed off rather than held as sacrosanct.

Within this framework, he then adds some stimulating layers all his own, many of them having to do, as in Hamlet, with the modern world’s technological obsessiveness. Iachimo convinces Posthumus of his beloved’s sexual impurity with the help of iPhone and iPad apps. Cloten jealously keeps tabs on Imogen through her browser history (his line “this paper is the history of my knowledge, touching her flight” resonates in whole new ways). There’s an aura of disconnection around the characters that feels very of the moment; one of Almereyda’s most provocative choices is having the two kidnapped white princes never question their blood relation to the black Belarius. And when all the masks finally drop, Cymbeline’s climactic observation (“Pardon’s the word to all”) resonates with boundless profundity—a benediction for an entire race blinded by greed, envy, and jealousy that has, if only momentarily, clawed its way up to a state of grace.