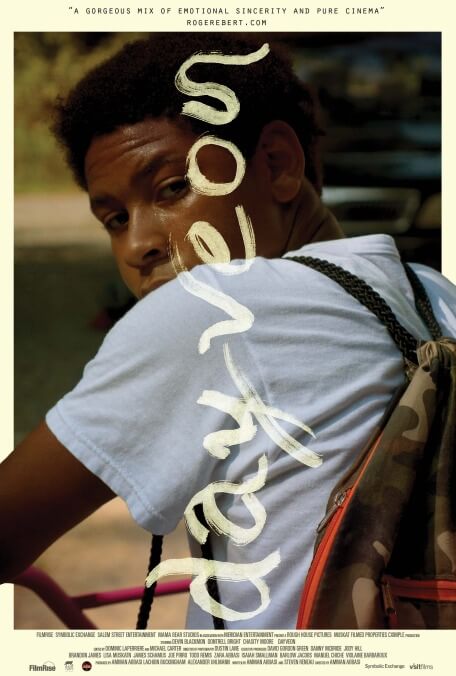

Voice-over in movies is so lame so often, even or especially when it’s supposed to function as an attention-grabber, that a genuinely distinctive voice-over track can produce an immediate and powerful reaction—exactly the kind of hook that the technique usually aspires to. Such is the case with Dayveon. Opening on a series of semi-overhead following shots of its 13-year-old title character (Devin Blackmon) riding his bike, the audience hears either Dayveon’s inner monologue or an amplified version of his speech as he ticks off a petulant list of things that are stupid. Anything in his field of vision is eligible: stupid tree, stupid house, “stupid bike I’m on.” The camera keeps its distance, but his muttering feels intimate and personal. It hooks the audience into Dayveon’s frustration and immaturity with a rare urgency.

Having done this, the movie then more or less dispenses with additional voice-over, except in a couple of sequences where dialogue plays over a montage. As it happens, that opening sorta-monologue from Dayveon has a verbal clarity that the movie often prefers to eschew. In many scenes, director and co-writer Amman Abbas lets his dialogue blend together in a blur of overlaps, seeming improvisations, and mumbly Southern accents (at one point, Dayveon has his gangly buddy Brayden repeat a girl’s name five or six times before he gets the pronunciation). There’s a low, almost musical hum of life to scenes that might otherwise feel sleepy.

These characters live in rural Arkansas, which is why it’s a little surprising early on to see Dayveon jumped into a gang—the Bloods, no less, though their direct affiliation with less rural outposts of their namesake gang is unclear. Dayveon lives with his older sister, Kim (Chasity Moore), her boyfriend, Brian (Dontrell Bright), and their very young son; he’s also haunted by the memory of his deceased older brother, whose airbrushed in-memoriam portrait hangs in the living room. It’s implied that his brother was done in by gang activity—he was shot—but Dayveon still looks to the Bloods for a sense of purpose that he doesn’t get from a loving but economically stretched home life. Brian sees what this kid hides from Kim, and tries to set him straight, but he has his own responsibilities.

All together, not a lot happens in Dayveon; even the gang members sometimes have to drive for what seems like hours through town to get up to no good (and Abbasi clearly loves plunging the camera into backseat darkness, highway light flashing and fading). Dayveon and Brayden (Kordell Johnson) have plenty of summer downtime in between their possible gang initiations, and they spend that time acting like typically restless 13-year-olds. The movie has a dreamy take on kitchen-sink indies not unlike the work of David Gordon Green, who executive-produced this film alongside his frequent collaborators Jody Hill and Danny McBride (Abbasi is credited as Green’s assistant on a couple of his recent films). This means that even when Dayveon and Brayden practice flashing gang signs, they do so in a cricket-scored magic-hour reverie at the edge of a pond where they also lazily skip stones.

Abbasi, shooting in an almost-square 4:3 aspect ratio, clearly shares some aesthetic tastes with his former boss, and the tone-poem approach to this material has its limitations. Like the movie’s 75-minute running time, Abbasi’s approach is both flexible and intentionally curtailed; at this point, the way a short story like this will and won’t resolve has formed its own kind of arthouse predictability. In the moment, though, Dayveon is often beautiful, anchored by a talented cast of first-time film actors. By displacing some familiar gang-movie dynamics into an environment less often glimpsed on film, Abbasi stays true to the offbeat heart of his influences. The strength of his work here indicates an even more distinct voice might yet emerge.