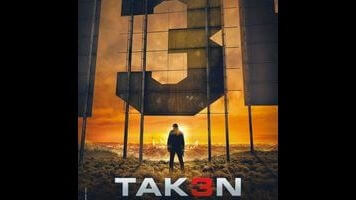

Taken 2 tried to one-up the original’s “kidnapped abroad” setup, but ended up producing something that only felt louder, uglier, and a lot less fun. Kudos to Taken 3, then, for at least trying something new. Instead of rescuing a family member from Albanian mobsters in yet another world capital, Bryan Mills—the throat-punching, elbow-chopping ex-CIA operative most people think of as simply “Liam Neeson”—finds himself framed for murder in L.A. It’s a conventional riff on The Fugitive, complete with Forest Whitaker in the Tommy Lee Jones role, but at least it’s tapping into a set of fears and fantasies—about divorce and being replaced by a step-parent—that are distinct from those of the original.

What makes Mills compelling—aside from Neeson’s performance, naturally—is the fact that his cartoonish over-preparedness and ability to escape from any situation are rooted in anxiety. He’s the perfect father for a kid who’s been kidnapped by armed thugs, but over-protective and awkward otherwise—a fact that Taken 3 underscores when Mills, who can effortlessly elude the best and brightest of the LAPD, slumps over after learning that his now grown-up daughter Kim (Maggie Grace) is pregnant. He’s an invulnerable action hero for the same reasons why he’s a difficult parent and partner.

So what, exactly, is wrong with Taken 3? A lot of things, most of which can be attributed to the fact that director Olivier Megaton—who also helmed Taken 2—couldn’t mount an action scene if his life depended on it. Pierre Morel, the cinematographer-turned-director behind the original Taken and the parkour flick District B13, at least had the good sense to move the camera with Neeson, playing off of his size and heft to create momentum. Making good on his name, Megaton takes the quantity-over-quality approach, executing a flurry of cuts across as many sloppy angles as possible, producing a gurgling brownish soup of photochemical textures and handheld jitters. This is the sort of movie where it takes a half-dozen shots for a man to jump over a fence. It’s busy, but lacks any sense of movement, and is too visually monotonous to work on an abstract level.

Because Mills’ hyper-competence never seems exciting, it instead becomes giggle-inducing. While, at this point, co-writers Luc Besson and Robert Mark Kamen are clearly milking the character’s tendency to speak in super-serious declaratives for intentional laughs (how else can one explain lines like, “I put something in the yogurt to make you nauseous,” and, “I have low blood sugar because I haven’t eaten since yesterday”?), it’s safe to presume that the high point of a sequence where Mills breaks into an LAPD garage isn’t supposed to be the shot of our towering, sixtysomething hero casually sliding out of the trunk of a car. Running a solid reel longer than either of its predecessors and featuring the worst car chase in recent memory, the movie amounts to little more than generic action slop, enlivened only by brief glimmers of intentional and unintentional comedy.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.