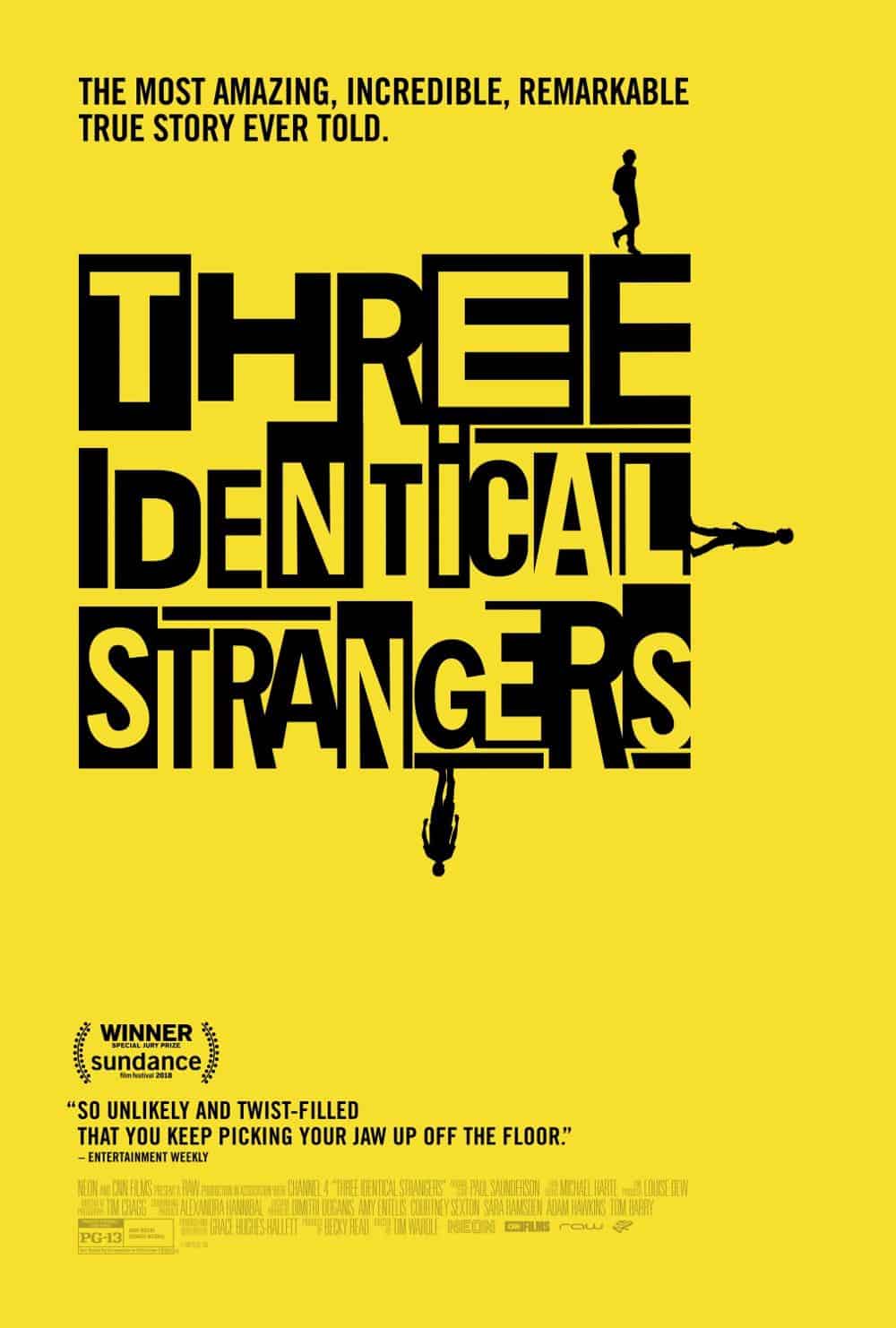

The true story of Three Identical Strangers gets crazier at every turn—and then seriously disturbing

There are three different potential audiences for the documentary Three Identical Strangers: 1) people for whom that title signifies nothing in particular; 2) people who’ll immediately recognize which ’80s human-interest news story the film must recount, but only know the basics; and 3) a handful of folks familiar with the entire insane saga. Those in group one should read no further, for now—just see the film, which is a truly mind-boggling ride if you have no idea what’s coming. Group two should bookmark and bail after the next paragraph, in order to be properly flabbergasted by revelations in the doc’s second half that are somehow even more incredible than the part they already know. And is there anything in this movie that might startle even the jaded denizens of group three? Indeed there is, albeit not necessarily in the way that they’d expect. So bizarre is this story that its most mundane aspects take on a certain profundity. Even when Three Identical Strangers falters, it fascinates, and that’s a claim very few documentaries can make.

Director Tim Wardle wisely lays the whole thing out in chronological order (starting from a certain specific point), allowing the subjects to relate what happened as they experienced it. Arriving for his first day of college in 1980, Bobby Shafran was perplexed to find himself repeatedly greeted by total strangers, all of whom called him Eddy. His campus doppelgänger was no mere look-alike, as it turned out. Eddy Galland, both men instantly realized when they met, must be Bobby’s identical twin brother, even though neither had ever been told of the other’s existence. So far so mildly interesting (mostly for the coincidence of their winding up attending the same school), but when the reunion appeared in newspapers, complete with a photo, another young man, David Kellman, found himself looking at himself, doubled. The triplets subsequently went on a media blitz, even briefly appearing in Desperately Seeking Susan; all three expressed nothing but joy at having found the missing pieces of their lives, frequently finishing each other’s sentences in the process. As the years went on, however, rifts developed. A tragedy occurred. And that was all before the truth of what had happened in their infancy was fully known.

It’s at this point that Wardle overreaches a little, attempting to construct a detailed nature-vs.-nurture thesis based on the triplets’ eventual discovery—last chance to eject, groups one and two—that they were separated, in common with numerous other identical siblings, as part of an illegal and downright diabolical scientific experiment, engineered via one particular adoption agency. Efforts to get hold of the relevant research have remained fruitless, which forces the film to end on an inconclusive note; instead, the sad fate of one brother (whose absence from the talking-head interviews portends bad news long before said news gets disclosed) is blamed on parental variation in a way that seems a little too facile. At the same time, though, Wardle’s savvy choice to film Robert and David separately until the final minutes, even avoiding many direct cuts from one to the other, quietly speaks volumes about the ultimate limitations of genetics. At age 19, they could scarcely be distinguished. Today, at age 57, a glance will suffice. Unethical researchers may wreak horrific emotional damage, but it’s nothing compared to the ravages of time.