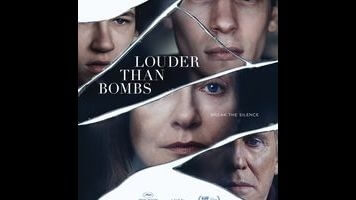

The truths land Louder Than Bombs in this stylish, sensitive family drama

Louder Than Bombs, the first English-language movie from Norwegian director Joachim Trier (Reprise, Oslo, August 31st), plays like an adaptation of some imaginary classic of modern literature, the kind you always assumed was too interior to ever be properly translated to the screen. The film takes a familiar, almost universal premise—the aftermath of a death in the family—and explores it through an intoxicating mélange of flashbacks, dream sequences, dream sequences within flashbacks, multiple narrators, poems transformed into feverish montage, and scenes staged and then restaged from different perspectives. These stylistic tricks open windows into the hearts and minds of the characters. They also make a movie about people grappling privately with their emotions feel energetic, even thrilling, in its own melancholic way.

The people are three bereaved souls, a father and his two sons, and their emotions all orbit an absence, the black hole opened up by the suicide of wife, mother, and famous photographer Isabelle Reed (Isabelle Huppert), who swerved into oncoming traffic on a lonely stretch of highway one awful evening. Several years later, as a museum prepares a posthumous exhibition of her work, a close colleague (David Strathairn) begins writing an extensive tribute for The New York Times, through which he plans to disclose that the car accident wasn’t an accident. This creates a certain problem for her widower, retired actor Gene (Gabriel Byrne), and eldest son Jonah (Jesse Eisenberg), a young sociology professor, neither of whom has ever explained the circumstances of her death to youngest son Conrad (Devin Druid), now a taciturn, withdrawn high-schooler.

Louder Than Bombs unfolds across a few short days, as these three survivors converge at their suburban New York home, father and son diving into boxes of Isabelle’s unfinished work while butting heads about how to finally break the tough news. But the film also stretches back further, hopscotching into the past to examine the separate relationship each of the Reed men had with this elusive, brilliant woman, sometimes a distant presence in their lives even before she died. (Huppert, with her air of removed intelligence, is perfectly cast as a restless genius—someone too ambitious to ever truly settle down and give up the rush of snapping photos on the frontlines.)

Jonah, a brand new father himself, is a variation on a common Eisenberg character, introduced as early as The Squid And The Whale and tweaked most recently in the form of Lex Luthor: the condescending egghead. Jonah harbors some resentment for his father, and he relates to his younger sibling as a kind of amusing curiosity, harping on his social maladjustment (“You’re not gonna, like, shoot up a school someday are you?”) when not genuinely marveling at the kid’s creativity, expressed through a free-associative personal essay that Trier adapts into a dazzling short-film-within-the-film. But big brother’s got his own issues: Sorting through his late mother’s unpublished photos provides an easy excuse to delay the responsibilities of marriage and fatherhood and reconnect with an old college flame (Rachel Brosnahan).

Gene, meanwhile, dips his toes back into the waters of romance, carrying on a secret relationship with one of Conrad’s teachers (Amy Ryan); the film introduces their courtship through a memory that Byrne narrates in second person—just one of many ways that Trier invigorates ordinary exposition. Gene also makes a few ill-fated attempts to really talk to Conrad (an experiment with connecting through the kid’s favorite pastime, Elder Scrolls, fails spectacularly), but the two can’t seem to get a handle on each other: There’s a great early sequence of the father creeping around town and spying on his son, which Trier then replays from the opposite point of view, to emphasize the lack of understanding between the two. Of course, Conrad, like a lot of young men his age, lives chiefly in his own head, and Louder Than Bombs visualizes his complex interior world, showing us how his mind wanders from a classmate crush (Ruby Jerins) to speculative visions of his mother’s death and back again.

Just about every performance here is understated, with Byrne—an actor probably best known for playing cold Irish gangsters—conveying more vulnerability than he maybe ever has, while Druid proves that the naturalism he exhibited as a young Louis CK was no fluke. Though it certainly demonstrates how much U.S. cinema benefits from a European sensibility, Louder Than Bombs is a remarkably confident American debut for Trier, whose work with the actors never betrays a language barrier, to say nothing of how precisely he captures his upper-crust East Coast milieu. Then again, Trier’s previous triumphs—coauthored, as this one is too, by Eskil Vogt, an accomplished director in his own right—weren’t culturally specific in their psychology: The damaged young men of Reprise and Oslo, August 31st could hail from any place where people yearn for the promise of their salad days and obsess about bright futures that will never arrive. There is no present tense in a Joachim Trier movie. His characters are always disappearing into their memories or fantasizing about what’s still to come.

Appropriately, for a film about something as gradual as grief management, Louder Than Bombs doesn’t attempt to reach some big, dramatic resolution. There’s no shouting-match confrontation, no cathartic scene of these three men finally and fully working through the damage loss has done to their family. The fireworks here are all of the formal variety, Trier using his deep bag of tricks to express the mess of feelings his characters can’t quite communicate. This is a movie of significant moments, nearly all about connection: two teenagers of different social strata sharing a lovely, fleeting communion as night bleeds back into day; two men—rivals in romance—discussing the woman they both loved, as well as either of them could; and two brothers marveling over how young their father once was, as Trier—in a trick borrowed from Steven Soderbergh’s The Limey—uses footage from Hello Again to conflate the past of a character and the actor playing him. It’s a film as complicated as the fictional lives it depicts, big insights echoing like the distant roar of explosion.