“Perchance To Dream” (season 1, episode 9; originally aired 11/27/1959)

In which a man sees a psychiatrist about a sleeping problem he’s been having…

Way back in the first week of this series, I talked a bit about how The Twilight Zone forms a sort of bridge between the anthology dramas of the 1950s and the more modern forms of drama that sprung up in the 1960s. It’s decidedly of the time period it was initially conceived in, but it’s also experimenting with form and content in ways that later dramas would push even further. The early anthology dramas were, essentially, filmed stage plays. Most of the hit ones were performed live, captured and sent out to the nation immediately, preserved (if you can call it that) on kinescope, which is why we have so few of them today. The live drama set-up was very similar to the live studio audience comedy set-up, with multiple cameras capturing what happened, and a director choosing the camera to cut to for maximum effect, based on the blocking. (None of this should be taken as absolute: Plenty of anthology dramas weren’t sent out live, though most of the popular ones were.)

Rod Serling, of course, came out of this world of anthology dramas. Thus, The Twilight Zone had plenty of episodes that might have fit just as easily in the world of live productions, where things were often confined to one set (or a small handful of sets) and a minimum of actors. Though Serling was not responsible for the script for “Perchance To Dream,” which was written by Charles Beaumont (and is, thus, the first non-Serling episode in the series’ run), it’s definitely of the sort that could have been produced as a spare, limited production on just one set. Indeed, it very nearly is, as the bulk of the action takes place in a psychiatrist’s office, as his new patient describes to him his unusual belief that if he falls asleep, he will die. It’s easy to imagine a version of this script confined to the stage, done as a one-act play.

But what makes “Perchance To Dream” so interesting and what makes it a good episode of television is the way that it doesn’t just allow itself to be trapped by the stage-y setup of the story. The most obvious example of this is the way that Beaumont’s script takes us into the man’s nightmares and lets us see what he sees when he closes his eyes. But there are also several nicely handled directorial and cinematic flourishes within the psychiatrist’s office itself, as the camera swoops in on the man’s face or whip-pans from a painting of a boat he says he can make move if he thinks about it hard enough back to his face. The direction—by Robert Florey—makes the office seem small and confining, the sort of space that might belong to the man’s nightmares, which is exactly what it is, we learn at episode’s end. The Twilight Zone takes something that might have been confining—the one-set nature of the premise—and turns it into something that would work only in filmed art.

Richard Conte plays Edward Hall (our man who’s afraid to fall asleep) as a raw nerve, up and walking around. He’s been up for over 80 hours when the episode begins, and he very nearly falls asleep while standing up several times. He’s got to keep going, got to keep moving. At the same time, John Larch’s Dr. Rathmann provides a pragmatic, slightly skeptical counterpart to the obsessive, slightly off-his-rocker Edward. There are two things at play here. First of all, this is a seriously weird premise, and it’s one that could very well fall apart under the slightest bit of scrutiny. And secondly, this whole setup could make for something incredibly claustrophobic if the actors don’t sell it perfectly. There are only three people with serious speaking parts here—Conte, Larch, and Suzanne Lloyd as a mystery woman—and all three of them nail what they have to do exactly.

This is a good thing, both because Twilight Zone always benefits from committed performances and because at all times, this is threatening to fall utterly apart. The score, dominated by what sounds to me like a theremin, comes perilously close to being too goofy to work with the rest of what’s going on. The very premise is strange and strained. And the nightmares are stylized within an inch of their lives, until the Dutch angles and hazy filters on the camera threaten to make everything seem like a parody of a Twilight Zone nightmare.

But what saves it all is everyone’s utter conviction in the idea that this makes sense. Of course there’s a strange cat woman chasing Edward through his dreams. Of course he’s got a heart condition that could never survive a significant shock to the system. Of course the receptionist in Lachmann’s office is Maya, the woman from the dreams, even if Lachmann insists she’s not. And of course Edward laid down as soon as he entered the office and immediately died. His dream seemed to last for quite some time to him, but to Lachmann, it was a matter of a few seconds. Maya—or whoever she was—finally got him in the end, tracking him across several episodic dreams and getting him to leap out of a window and off himself. I don’t know how widely spread the idea of “if you die in the dream, you die in reality” was when this episode aired, but this has to be one of the first instances of that trope committed to film.

Another thing that works here is that nothing ever stops to try to explain what’s going on. The episode just keeps piling wacky idea on top of wacky idea, until the whole thing feels like it could topple over at any moment, even as it manages to just stay upright. That mesmerizing monologue from Conte sets up the idea that if he just imagines something, it will pop into existence. Then he brings up episodic dreams. And then we’re at the amusement park that could only exist within a nightmare (and notice how Florey subtly brings some of the camera moves from the carnival right back into Lachmann’s office to signify that we’re still in a nightmare). The whole thing moves with the hazy logic of, well, a nightmare, and it captures that sense of being unable to wake up as well as any episode of this show that I’ve seen.

To that end, it also captures something fundamental in its main character: a kind of sexual panic. Maya is undeniably sexy (though I find her most attractive in her receptionist guise), and when she starts her dance of seduction for Edward at the carnival, it’s a moment that almost feels funny—particularly by modern standards of what’s risqué—but always stays on the right line of camp. Maya is relentless in her pursuit. Edward can’t get away quickly enough, because she’s always right there. And he knows that when he falls asleep, she’ll be back again. There’s next to no explanation of who Maya is, but consider that with Edward’s heart condition, sex would have to be very like death. This is a man who’s lived his whole life in a tiny little box being forcibly thrown out of that box, and he’s unable to deal with anything he discovers on the outside.

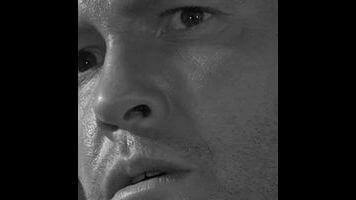

If I had to boil down just why I like this episode so much to a single sequence, it would come in the moment where Edward is talking about his nightmare of driving home along Laurel Canyon. (Or is it reality? I love how the episode will say definitively that something is reality or is a nightmare and then immediately start pulling the rug out from under us.) He just knows there’s someone in the car with him—like he read about in the papers—someone in the backseat, just waiting to kill him. And though he logically knows that’s not the case, he also knows if he keeps staring at the rear-view mirror, he’ll see the one who’s joined him. But when he finally sees this other, it’s not the sort of hulking figure you’d expect in a horror tale like this. It’s a woman’s eyes, brow quirked quizzically. The sequence, priming you for a big scare, instead sends you down the rabbit hole, and it immediately lets you know you’re alone, in the dark, with this guy, and there’s no escaping what’s coming.

What a twist!: Turns out that Maya from Edward’s dreams is also Lachmann’s receptionist, so he pitches himself out of Lachmann’s window, committing suicide. Oh, but wait! The second he entered Lachmann’s office, he laid down on the couch, and what we just saw was his split-second dream, the one that finally killed him.

Grade: A

Stray observations:

- I love the sequence on the roller coaster, which is as fine an evocation of what it’s like for a milquetoast guy like Edward to unexpectedly hook up with a seductress like Maya as I’ve seen.

- Favorite shot: Conte comes out of the nightmare about the roller coaster, and we see the close-up of his face, staring out at the world that no longer seems as safe as it did. I’m impressed with how long Florey holds this show.

- Beaumont wrote any number of additional episodes of the show, including the famous “Living Doll” (which we’ll get to… someday). The story that formed the basis for “Perchance To Dream” was originally published in Playboy, naturally enough.

“Judgment Night” (season 1, episode 10; originally aired 12/4/1959)

In which hell repeats itself

One of the things I find fascinating about The Twilight Zone is the way that it’s so informed by the events of the Great Depression and World War II, which seem, of course, like increasingly distant history to us in 2011 but were very much recent history to Serling and his production staff when making the show. World War II hadn’t even been over for 15 years yet when “Judgment Night” went into production, and there’s a certain understanding in this episode that the audience will instantly understand all of the twists and turns of the plot, will know what a U-Boat is, will remember that several non-military vessels were sunk by U-Boats over the course of the war. There’s a kind of purity to this episode, a relentless momentum that wants us to know that God has devised several clever punishments for those Nazi bastards.

Nazis, of course, remain among the few acceptable villains for American films. Since the fall of Communism, it’s become harder and harder for American moviemakers to come up with villains that will play to a broad, global audience without isolating anyone. Nazis work because, well, saying you sympathize with Nazis isn’t going to win you friends. At the same time, this has allowed Nazis to become more and more cartoonish, more like video game villains to be mowed down in waves by the hero. The recent film Captain America actually posited a kind of super-Nazi movement within the Nazi party, one that made for even goofier bad guys to kill.

If there’s one thing to be said for “Judgment Night”—which is not a very good episode of The Twilight Zone, all things considered—it’s that Rod Serling (who takes script credit again) isn’t reducing his main Nazi villain, Carl Lanser, to a buffoonish cartoon. No, Carl is portrayed as someone who perpetuated a deep evil and was punished by God for it. There’s a rawness and an immediacy to these events, the sort of thing that lets you know Serling lived through this time period, remembered the Nazi atrocities acutely, and not just as things he learned in a history textbook. The sequence where the U-Boat sinks the ship Lanser mysteriously finds himself aboard is legitimately horrifying, but not in the sense of being filled with ghosts and goblins (though, ultimately, it has plenty of the former). No, this is a sequence where innocent people are burned alive or dragged to the bottom of the ocean or shot down as they try to put a lifeboat in the water. It feels vivid and shot through with both anger and pathos. This is Serling working through some of the greater demons spawned by the war.

The episode isn’t perfect, particularly to modern eyes. It’s far, far too easy to guess the ultimate mystery of what’s going on with Lanser. (Serling’s narration, which more or less gives the game away, isn’t terribly helpful in this regard.) The idea of a hellish punishment that involves getting stuck in some sort of endlessly repeating loop that guarantees an evil man relives the final moments of the innocents he killed isn’t exactly a new one, but I rather wager this was one of the first presentations of that general theme on TV. But the half-hour format isn’t terribly great for character development, and “Judgment Night” starts from a fairly weak place to begin with, giving Carl a kind of amnesia that gradually fills in the blanks (even as the audience is caught up as soon as he says “Frankfurt” in the early dinner scene). This doesn’t make Carl interesting so much as it makes him a puzzle to be solved, and once the puzzle is solved, it’s hard to imagine wanting to get to know him any better. He’s a bad guy, through and through, and the only reason he’s interesting to us is because he’s being punished. Once we figure that out, the episode doesn’t have much more to offer.

Fortunately, there are some things worth checking this episode out for. Chief among them is Nehemiah Persoff’s performance as Carl, which is at once understated and very, very theatrical. Persoff is capable of going small in the scenes where he’s not quite sure who he is and very, very big in the scenes where he’s running around the ship, trying to let everyone know that the U-Boat—piloted by him—is coming to wipe them off the face of the Earth. There’s a fantastic moment where Carl has run below deck and is looking for someone—anyone—to alert of what’s about to happen, of the significance of 1:15, and he turns from the end of the long hallway he’s run down and sees a group of strange, sad people standing at the other end, staring at him mournfully. He turns, looking for more people. He turns back. They’re gone. It’s only slowly dawning on him that he’s in Hell, but Persoff makes you feel every single moment of Carl’s realization.

On the other hand, a lot of the episode is just too big for a half-hour TV show. The attempts to set up the other characters on the ship don’t really work, while the big climax where everything loops back on itself is marred by an obviously American actor sharing the screen with Persoff (who does a nicely modulated accent that isn’t immediately noticeable as German but is also immediately noticeable as not American). Poor acting does in lots of the scenes in the episode, which often seem to have been performed by a random summer stock company that’s decided to put on Anything Goes with Nazi war criminals. At times, Persoff seems to be the only one committed to making this whole ghost ship idea work. Similarly, the whole bit with the moral at the end is clumsy and hamfisted, with our other character telling Carl directly that he is being judged for his actions by God. Serling’s feelings—and by extension, the feelings of the others in his generation—toward the Nazis are palpable here, but there’s nothing subtle about any of this.

Too many times, The Twilight Zone boils down to its twist ending, and this is an episode where the ending is the entire purpose of the episode, even if there are other pleasures to be had. Expressing a moral in a story like this is fine, sure, but there’s a tendency when the moral is all you have to let it overwhelm the rest of what’s going on. At the same time, there’s a nice texture here, a nice sense of just what it was like to be in America in the 1950s and remember that just 15 years ago, you were fighting a menace that seemed very much like it might take over the globe and destroy everything you stood for. There’s nothing subtle about Carl Lanser, no, but the exact scale of his evil is an interesting look at just how Americans were processing the war they’d just been through slightly over a decade later. There’s not a lot here to enjoy story-wise, but historically, it’s a treasure trove.

What a twist!: Carl Lanser is the captain of the U-Boat that sinks the ship he now stands on. God has doomed him to constantly relive the last hours of the ship, to get to know its passengers and realize everything he destroyed, over and over for the rest of time.

Grade: B-

Stray observations:

- Silly as a lot of this is, I do really enjoy the sequences where it seems like the ship is a ghost ship, haunting the fogs of the Atlantic. I also like the little details here, like the ship snuffing out its lights to pass through the night undetected. It’s this kind of detail that’s easy to forget between now and then.

- It’s also incredibly obvious what’s going on here as soon as the people Carl sits with at dinner start waxing rhapsodic about how much they miss their families at home. Gee. I wonder if they might never see them again?

- I like how the porter is all, “Oh, here’s your GERMAN NAVAL HAT,” as if Carl might have needed it for his secret mission or something.

Next week: The Twilight Zone tries two of its favorite genres, with space tale in “And When The Sky Was Opened” and fairy tale in “What You Need.”

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.