The Twilight Zone: “The New Exhibit”/“Of Late I Think Of Cliffordville”

“The New Exhibit” (season four, episode 13; originally aired 4/4/1963)

In which the figures are alive. ALIVE!

(Available on Hulu.)

Here’s an idea that would make a good, creepy episode of just about any anthology series. Indeed, it’s an episode that might be hurt a little by the standard Twilight Zone twist, one that almost feels like it would fit more comfortably on Rod Serling’s later series Night Gallery. The idea of an employee of a wax museum becoming so attached to five figures meant to represent some of the most horrifying murderers in history that he moves them into his basement and starts bankrupting himself to care for them is just a marvelously creepy notion in and of itself. It almost doesn’t need those figures to start coming to life and killing people, but once it does, it feels like the logical progression of events. You wanted this evil in your basement, buddy. Better learn to live with it.

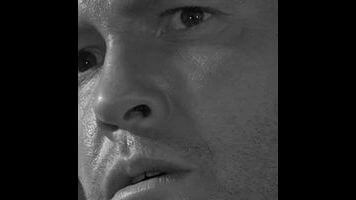

Written by Charles Beaumont (about which more in a bit) and directed by John Brahm, “The New Exhibit” is yet another episode where I get to say that an hour-long edition of the show feels padded and overlong, but it’s also one of the few episodes this season to turn that flaw into something of a strength. The way that everything seems to have a little too much space adds to the tension, particularly when one of the characters is wandering around those wax figures, and the extra padding adds to the dreamlike feeling of the episode. One of Brahm’s choices, one that could feel chintzy but somehow doesn’t, adds to the episode’s nightmarish streak as well. By filming the wax figures—who are obviously real actors in heavy makeup—in extreme close-up, then holding on still frames instead of asking the actors to hold a pose for as long as the camera is on them, Brahm’s camera makes the figures seem somehow more lifelike than if the actors were playing freeze tag. It looks like a still frame, and we’re used to still frames capturing movements in process. It feels as if Jack the Ripper might lunge out at us at any second.

Significant praise also has to be handed out to the cast here, particularly Martin Balsam as our main character, Martin Lombard Senescu. Balsam is most famous for his work in Psycho and A Thousand Clowns (for which he won an Oscar), but he was always a natural fit in the Zone, and this is another episode that proves his slightly bugged-out performances match nicely with the series’ weird and fantastical nature. Balsam plays both halves of the character’s self—both the part of him that wants to preserve these figures to the point where he might commit murder and the part that seems to be an otherwise normal man who loves his wife and friends. There’s a moment early in the episode when Martin has just made the deal to bring the figures into his home and has already seemed a little eerie and off about it all, and then the story cuts to his home, where his wife is nervous about the whole enterprise and he has to assure her it’s all right. Balsam plays both scenes so convincingly that it’s easy to forget just how weird all of this is, just how much his wife has a good point about the oddity of keeping these monstrous figures in her home.

The rest of the cast is quite good as well. As Martin’s wife, Emma, Maggie Mahoney reminds me of Breaking Bad’s Skyler White: An obviously sane woman wondering how the man she loves has seemed to completely lose his mind when these figures are around. As Martin’s friend and boss, Mr. Ferguson, Will Kuluva offers up a solid bedrock for Martin to fall back on. When Ferguson is finally killed by the figures, it seems like the bottom has fallen out of the episode without his presence around, and that’s the feeling so many of the best episodes of this show inspire. As the five figures, Milton Parsons, David Bond, Bob Mitchell, Robert L. McCord, and Billy Beck are mostly just asked to stand around and look menacing, but they do an excellent job of it, and when any one of them finally moves, it’s exactly as you’d expect a wax figure to move: stiffly and slowly but with deliberate intent.

There’s not really much story here—the second all those wax murderers are introduced, you’re waiting for them to start murdering, and they take their sweet time before doing so—but I’m not sure there needs to be. The central conflict throughout isn’t so much about whether the wax figures are doing what they’re doing—we get to see them move the three times they kill—but about just how devoted Martin is to those figures. By hinging the whole episode on the sanity of a man we’re first introduced to as an appreciator of the finest the wax medium has to offer and friendly tour guide, Beaumont and Brahm give Balsam further to fall, and Balsam is only too happy to chew every last bit of scenery on his way down in highly entertaining fashion.

There’s a sadder undercurrent to this episode, as the script credit to Beaumont isn’t strictly correct. Though the initial idea was his, the entirety of the episode was plotted out by Beaumont and a young writer named Jerry Sohl, and Sohl wrote the final script with little to no input by Beaumont. Beaumont used a fair number of ghost writers, against Writers’ Guild regulations, and many (including Sohl) would go on to have great careers of their own. But while Beaumont had done this in the past because he simply had too much work to do, by the time “The New Exhibit” was going into production, he was in the full grip of the mental condition that would take his life by 1967, degenerating his mind to the point where he could no longer remember things or follow the narratives of movies and prematurely aging him, so when he died, he appeared to be an elderly man, even though he was only in his 30s. (For the full story, Marc Scott Zicree’s Twilight Zone Companion is, as always, recommended.) Scripts for the Twilight Zone would continue being credited to Beaumont throughout its run, but all were ghostwritten. His great career—which was still young and still held so much promise—would be snuffed out in its prime.

This isn’t one of the finest scripts credited to Beaumont—that would be season two’s “The Howling Man” or season four’s gorgeous “Miniature,” which resonates so much more when one realizes just how desperate Beaumont must have felt while working on it—and its twist ending ultimately undermines it in some frustrating ways. (I choose to believe that the wax figures are merely trying to convince Martin that he was the murderer, when they were really the ones to carry out the acts, but that’s not really supported by what’s on screen in any way.) It’s also, again, fairly drawn out in ways that sometimes hurt it and not really supported by much in the way of plot. Yet knowing about Beaumont’s biography and looking at this episode make everything a little more poignant in unexpected ways. This is a story about a man hurting those he loves most because he can’t quite get a bead on what’s happening in his own head. Viewed in those terms, the episode seems almost something more.

What a twist!: Martin is the one who committed the murders, and he’s later memorialized because of this fact as a wax figure, forever to live with his wax figure friends.

Grade: B+

Stray observations:

- The final moments when the figures all turn and move toward Martin as one unit are appropriately ghoulish, and I also like wax figure Martin quite a bit (as seen above).

- In terms of bit players, the sailor who takes Martin’s tour at the episode’s beginning is pretty fun. I like how he allows himself to get creeped out by the whole thing.

- Interesting reminder that it’s 1963: Air conditioning is a weird luxury that could very, very easily bankrupt the Senescus.

“Of Late I Think Of Cliffordville” (season four, episode 14; originally aired 4/11/1963)

In which Rod Serling needs to get over his fetishizing of small towns in the Midwest in the first half of the 20th century already, God.

(Available on Hulu.)

This is my second Twilight Zone article in a row where I’ve had to deal with an episode about a guy who travels back to a small town in Indiana in what was the relatively recent past in 1963, only to find that it’s not all it’s cracked up to be. This sometimes happens on this show, where the writers seem to get worked up by a particular setting or subject. (It happened in season three with stories set in the Appalachian backwoods.) What’s different here is that the same writer was responsible for both episodes—which aired around a month apart. That writer was Rod Serling, and who knows what the hell this particular scenario held for him, because he returned to it over and over and over again, to diminishing returns. “Of Late I Think Of Cliffordville” is a distinct step down from “No Time Like The Past,” and I didn’t like that episode very much to begin with.

To be sure, as someone with a great deal of nostalgia for the small town of my own youth, I can understand what about this idea is so intriguing to Serling, but you’d think by now he’d have realized he had said everything he could about it. And there’s at least an attempt at a new spin in “Cliffordville,” in that the man who gets to travel back in time hasn’t properly thought through all of the consequences of going back (in rather an unrealistic fashion, if I do say so). But that is already fairly close to what Serling was up to with “No Time Like The Past,” and it’s in the same general family as every one of these episodes, where the easy allure of an American small town sometime between the years of 1880 and 1920 is revealed to be hollow.

“Cliffordville” means to be a tale of comeuppance, and it’s relatively successful at that, I guess. The problem is that the man receiving said comeuppance—a rat bastard old millionaire named Feathersmith—is mostly just irritating. If you want to do a riff on the Ebenezer Scrooge story, then you need someone who’s sort of fun in his irritation. In A Christmas Carol, Scrooge gets knocked around a bit, and when he goes into one of his rages, the things he’s raging at—like Christmas—are so well-liked that the joke is ultimately on him. Feathersmith is just kind of a dick to a bunch of people we’ve never met, which requires a lot of exposition about how everybody knows each other that starts the episode off at a crawl. It also doesn’t help that the man playing Feathersmith—Albert Salmi—isn’t a very convincing actor, choosing to portray his assholery by reading every line as if he learned it phonetically. Nor does it help that the episode’s old-age makeup is pretty bad. (Casting different actors across the two timelines might have worked better.) The central idea of Feathersmith’s character—he thinks the getting of riches is more exciting than the having—isn’t a bad one (and certainly describes more than enough billionaires in the present), but Feathersmith too often seems, well, kinda dumb.

There’s one thing here worth heartily recommending, and that’s Julie Newmar as the devil, here known as Ms. Devlin. The scene where Feathersmith and Devlin negotiate the terms of his contract is the best in the episode and a lot of fun. The idea that Feathersmith has already signed his soul over to Satan via causing so much ruin and despair in his business career is a good one, and I also like that the devil apparently needs cash, thus asking Feathersmith to sign over all but a little over $1,400 of his considerable fortune. Because this is the devil and because this is Feathersmith, it’s always obvious how this is going to turn out, but Newmar is great in the part, at once sexy and sarcastic. It’s a good mix, and I wouldn’t have minded if the episode were just about her.

Instead, we follow Feathersmith back to Cliffordville, and while there are some clever ideas here, Serling can never settle upon just one. (This is similar to how the characters of Diedrich and Hecate serve roughly the same function within the story, but they’re both there to pad out the running time.) The idea that Feathersmith has misremembered his youth—forgetting about muddy horse tracks and the horrible warbling of the young woman he was courting at the time—is probably the most promising of these, but Serling doesn’t really do anything with it after the scene where he goes over to the house of his potential lady love. Instead, Serling goes all in on an idea that doesn’t really work: Although Feathersmith asked the devil to make him appear to be a young man, he didn’t ask her to make his mind and organs young as well.

The reason this idea doesn’t really work is because it comes out of nowhere. When Feathersmith arrives in Cliffordville initially, he runs around, practically kicking up his heels at his good fortune. It seems less like the behavior of an old man clothed in a young man’s form than an authentically young man. And it’s also not really necessary that Serling cloak all of this in that conceit because it’s wholly believable that, say, Feathersmith wouldn’t know how to build a drill to get down to the oil buried beneath the land he just purchased. (Again, however, this makes him seem a little too dumb to be believed. He wouldn’t have considered there might be a reason that oil wasn’t extracted until 1937?) It’s all a rather weak idea, and once it’s revealed, the episode just keeps forcing Feathersmith to make idiotic choices—like listening to advice from the devil herself when she’s already gotten him in this mess—because it needs him to uphold its morality play framework by playing the custodian to Hecate’s businessman in the too-predictable final scene.

The thing Serling wants to communicate isn’t a bad idea: Feathersmith thinks he’s someone who worked for his money, a wheeler-dealer who created his own success. But in reality, he was just a leech and a mooch, destroying others’ businesses and raiding the ruins to line his own pocketbooks. It’s meant to be another of Serling’s incisive eviscerations of the darker side of capitalism. But “Cliffordville” is too padded and too repetitive of other episodes in the series’ run to ever really manage that trick. It’s one good performance in Newmar, then a whole bunch of dross, much of it the sort of thing the show has shown you many, many times before.

What a twist!: After selling Hecate his oil-rich land to get the money necessary to return to the present, Feathersmith becomes the janitor and Hecate the businessman.

Grade: C-

Stray observations:

- I love the look on Salmi’s face when Feathersmith first sees Devlin with her horns. It’s the look of a businessman who’s always wanted to deal with someone his equal and has finally met the ultimate dealmaker. If the characterization of Feathersmith had skewed more toward that, this episode might have worked much better.

- Director David Lowell Rich sure overworks the Dutch angles and fancy camera spins to make Feathersmith’s confusion and isolation in the past feel more acute, huh?

- Go rewatch that opening scene with Feathersmith and Diedrich to watch as Serling attempts to fiiiiillll aaaaaaaasssssss muuuuuuuuchhhhh tiiiiiiiiiiiimmmme asssss heeeee caaaaan.

Next week: Zack heads into “The Incredible World Of Horace Ford” with the great Reginald Rose, then learns that “On Thursday We Leave For Home.”