The Twilight Zone: “Where Is Everybody?”/“One For The Angels”

“Where Is Everybody?” (season 1, episode 1; originally aired Oct. 2, 1959)

In which the world is abandoned, but for one man

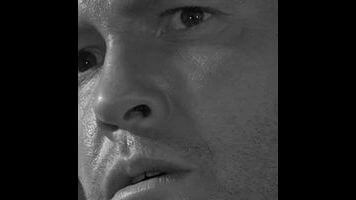

If there’s a single shot that encompasses The Twilight Zone at its most basic essence, it’s the one pictured above: a man, framed in extreme close-up, staring in horror toward something he doesn’t quite understand. Sweat beads his face. His eyes are wide open with recognition of just how alien the situation he finds himself in is. His mouth partially hangs open in horror. He’s crossed the line between the normal and the abnormal, between reality and fiction. What’s worse, he realizes it. He’s wandered off course and into some new world entirely, a world perhaps known—at least as Rod Serling would have it—as the Twilight Zone.

The Twilight Zone is probably one of the 10 or 15 most influential television programs of all time. It grew from modest beginnings—as a middling performer on the CBS network, there was always a threat of at least theoretical cancellation hanging over its head, even if it hung on for five years and over 150 episodes—to a sensation in syndication, where its parables of Cold War America went from clever little horror/sci-fi stories to the sorts of things that seep out into the culture at large. Many of the show’s episodes are so famous that even people who haven’t seen them know the twist endings—“It’s a cookbook,” “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” broken eyeglasses, take your pick—and the show’s popularity is such that it remains one of the few shows of the era (and the only anthology drama) to be consistently syndicated to this day. It also straddles the line between the popular dramatic programs of the ’50s and the sorts of dramas that would follow. And as a science fiction program, only Star Trek can really compete for level of influence.

But why this show and not one of the several other sci-fi anthologies that sprung up in its wake, many of which were solid-to-very-good in their own rights? The Twilight Zone contains some of the best pieces of television ever made, to be sure, but it also contains some desperately undercooked clunkers, some episodes that make one wonder just what Rod Serling thought he was doing with this foundational document of American pop culture. Serling—a highly acclaimed TV writer even before this show debuted, one who was responsible for what was, at that time, the most awarded production in TV history, “Requiem For A Heavyweight”—never met an unsubtle political message he couldn’t shoehorn into the middle of a perfectly enjoyable science fiction tale. (His scripts are often the worst in this regard.) For every wonderful parable that still holds up that he turned out—“The Monsters Are Due On Maple Street”—there were others that made their points and then kept hammering away at them.

The answers, I think, are evident right away in what became the series’ second pilot, “Where Is Everybody?”, which is the tale of a man who stumbles into a small town that’s apparently been deserted entirely, but for him. Is he the last man on Earth? Is he dead and wandering through Purgatory? Or has he somehow stumbled upon a nuclear test site where he’s about to be incinerated by a hydrogen bomb? All of these possible solutions must occur to most viewers as they watch the episode, particularly as they consider that, well, this is a show famous for its twist endings.

And what’s remarkable is just how stark Serling and episode director Robert Stevens allow this to be. The vast majority of this episode is basically a one-act play, a man wandering around one location and yammering away to himself for the benefit of the audience, which might otherwise get restless. But there’s also a great deal of silence utilized to eerie effect here. Even today, we’re used to television constantly bombarding us with noise and music and sound, the better to keep us from changing the channel. “Where Is Everybody?” takes its time, and even after the twist lands, allowing for the man’s yammering to be written off as his mind finally snapping while in isolation, there’s still a desperate quality to his talk, something that makes his chatter just as unnerving as the empty town (with still smoking cigars and warm coffee pots on the stove) could ever be. This was one of Serling’s particular strengths—the ongoing monologue that doubles as a way to gradually creep the audience out—and it’s on full display here.

“Where Is Everybody?” is not going to be regarded as one of the series’ all-time classics by most, but it’s a surprisingly effective distillation of what makes the series work, and it works well as a pilot in that regard. The episode may get a bit repetitive (once the man wanders into town, it’s obvious it’s abandoned, and the bulk of the episode just continues setting up this one dramatic beat over and over), but it never gets old somehow, and I think that’s because it—like every other Twilight Zone episode—owes as much to the stage play as any other medium. Most of this could be adapted to the live theatre very well, and it’s there where the convention of a character talking aloud to key us into their thoughts is most celebrated.

But the episode also speaks to another reason the show became so timeless: It’s fundamentally a series about the loss of American (or maybe even human) innocence. Serling and the first round of TV drama writers were people who had lived through the Great Depression and Second World War. They were people who’d seen trials and tribulations and somehow made it through them, who now wanted to use the new bully pulpit they’d been handed to promote great old American values. Yet at the same time, they, in the tradition of TV liberals since time immemorial, looked out at the country they lived in and saw that it did a fairly poor job of living up to those values. And the specter of the atomic bomb hangs over every single one of these episodes, a monster that could end human life in a few minutes, if someone would just push a button. The Twilight Zone is all wrapped up in that terror, in that idea that the world as it should be is not the world that is and the world that existed before Hiroshima and Nagasaki is also not the world we’re living in anymore.

Take a look, for instance, at the twist ending of “Where Is Everybody?”: The man is revealed to be a prospective lunar astronaut named Mike Ferris. He’s been kept in an isolation chamber for over two weeks, in an attempt to simulate what it would be like for him to travel to the Moon. In the process of doing this, his imagination has wandered, and his mind has finally snapped, creating out of whole cloth a reality where he is the only man left and everybody else has skipped town. As always, there’s a blatant political point to be made here—there was some concern at the time about sending men into space in extreme isolation for long periods of time without any other human contact—but there’s also a more subtle question about American values at play. Do we value the individual at the cost of progress? The episode says yes, but the direction says no. The military men clearly tested this process on Ferris because they wanted to make sure he could handle it, and Serling puts a nice monologue about questions of aloneness and loneliness in the mouth of one of those men. But at the same time, when the brass are revealed, they’re all swathed in shadow, shot as if they were the secret conspiracy on The X-Files. And didn’t they put this man in the midst of that simulation in the first place, always knowing this could be the end result? You can say all men are created equal and you value the individual and community is important all you want, but what about when it comes time to beat the Soviets to the moon?

“Where Is Everybody?” isn’t a perfect episode by any means. There are parts where it becomes a little too stagey for its own good (the man’s discussion with himself in the mirror, for instance), and the script itself is often very repetitive. But there are moments here that mark themselves as classic Twilight Zone bits from the instant they arrive, like when the man rushes into the theater showing the movie, starting to remember who he is, then shrieks in anguish at the empty projection booth. The world is running as it’s supposed to be, but there’s something dark and terrible underneath it, something only one person can see in a moment of terrifying clarity. All he can do is stare in disbelief and terror. Every great episode of The Twilight Zone has that at its core, and that makes this an effective introduction to the series.

Grade: A-

What a twist!: The man who wanders into the deserted town is actually prospective astronaut Mike Ferris, stuck in an isolation chamber meant to simulate travel to the Moon and left to hallucinate the abandoned town.

Stray observations:

- Welcome to The A.V. Club’s Twilight Zone coverage! Zack and I will be trading off, at the rate of two episodes per week, for the foreseeable future. The plan at present is to alternate seasons of Twilight Zone with seasons of X-Files, but if this feature proves wildly, unbelievably popular, that plan may change. We’re also planning to follow air order, rather than production order. Some good resources to look into the show include this fan site and Marc Zicree’s Twilight Zone Companion. The complete run of the show is up on Netflix Instant, and several episodes are available on other streaming services. (Wikipedia also has a good page on the show, along with individual episode profiles, if that’s your thing.)

- This was actually the second Twilight Zone pilot produced. The first aired as an episode of Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse, and Zack and I will hopefully cover that episode as a special addendum, if we can track down a copy. (Why do I bet YouTube has it somewhere?)

- This was also Serling’s second script when asked by CBS to go ahead with a Twilight Zone series. The first, “The Happy Place,” apparently dealt obliquely with euthanasia and was, thus, rejected by the network.

- I’m always tickled when older shows use movies that were actually movies at the time, and the Rock Hudson vehicle playing in the theater is the actual Douglas Sirk film Battle Hymn. I’ve never seen it. Anybody out there have any insights as to how it might intersect with this plot (other than also featuring the Air Force)?

- The show was still without its famous theme song, and the Serling introductions haven’t yet found their clipped, efficient delivery just yet. All things in time, I guess.

“One For The Angels” (season 1, episode 2; originally aired Oct. 9, 1959)

In which there is something called a “pitch-man.”

I mentioned above that one of the major themes of The Twilight Zone is the shift from the pre-atomic age America to the post-atomic age America. “One For The Angels” doesn’t have nearly as much nuclear paranoia as “Where Is Everybody?”, with its empty town and endlessly smiling mannequins, does, but it certainly has an element of a world that was disappearing before most Americans’ eyes. At the center of the episode is an old “pitch-man” named Lou Bookman (played by Ed Wynn) who confronts a black-suited specter of death, played by Murray Hamilton. This is a fairly typical set-up of an old man who fears he hasn’t lived enough of life trying to find a way to cheat death, and the show doesn’t do much with it, honestly.

It’s also an example of something that would hurt any number of Twilight Zone episodes. The show had a penchant for sentimentality right from the start, and the series would often leave behind the science fiction and horror environs that usually suited it best (though not always) and take a trip to the land of the fairy tale. Serling, who also wrote this episode (Robert Parrish directed), had a love for the somewhat hacky and mawkish, and while “One For The Angels” isn’t the worst example of this from the show’s run, it’s certainly an episode that is nearly destroyed by the fact that everything here is either a very broad joke or the sort of tearful sentiment that might show up in a greeting card.

At the same time, the episode is, frankly, hurt by the fact that it was produced in 1959, and we’re living in 2011. Stuff that’s produced now will almost certainly look odd to our grandchildren 50 years down the line, and much of what doesn’t work here stems from some of the acting and production techniques common to the time. The worst scene of the episode is the one that should be the most pivotal. Lou has made a deal with Death that he will get to live until he makes the greatest pitch he’s ever made (the titular one for the angels), but he doesn’t realize that Death will have to take someone at midnight, if he can’t take Lou. This means that a little girl who lives in Lou’s building will be the replacement for Lou, after she runs out into the street and is hit by a car. Lou, realizing what he’s done, decides to save his little friend by distracting Death with a pitch session that will keep him from fulfilling his duty to take the little girl at midnight. As a setup, it’s a little goofy, but it works well enough as the basis for a fairy-tale storyline.

The problem, though, is that the “pitch” scene just simply isn’t convincing. The world of the street-corner salesman, there to shout out the wonder of the products he’s hawking was already in decline when this episode aired. (One of the nice things about it is how there’s a vague nostalgia for the world Lou comes from, the world that will soon enough disappear.) So on one level, it doesn’t make a lot of logical sense that Death would be so taken in by Lou’s excitement over synthetic silk. But the whole scene is rather clumsy, particularly in the acting, with Wynn all sweaty excitement and Hamilton all fidgety nerves, just certain he has to get whatever it is that Lou’s hawking. Plus, it’s another that goes on and on forever, endlessly repeating the same point. We see the little girl in bed, then we cut to her clock, which is 10 minutes from midnight. Then we see Lou pitching again, then the girl, then the clock, now only five minutes from midnight. To a certain degree, this kind of slower editing is forgivable in older projects where the pace the audience expected hadn’t been so artificially heightened. But this is a blatant stall, an attempt to draw out a scene that doesn’t really work, and it makes the episode feel even longer than it is. (Contrast that with the just-as-repetitive but somehow much tighter “Where Is Everybody?”, which perhaps succeeds because its central premise isn’t as preposterous.)

There are certainly good elements here. I quite like the initial scene where Death appears in Lou’s little apartment, particularly the way that he keeps moving about the room, so Lou always has to find him in a new location. I liked the scene where the little girl was struck by the car and could finally see Death waiting for her. And I like Hamilton’s portrayal of Death as a sort of coolly calculating businessman. (There’s actually a lot of Serling in the way Hamilton plays the figure.) But the rest of the story is unfortunately broad, particularly in Wynn’s performance, and it speaks to the fact that for all of its strengths, The Twilight Zone was rarely able to do comedy.

One of the reasons the show kept trying, of course, was because it came out of the world of the anthology series. Serling had made his name writing for the various “TV playhouse” type series before landing on The Twilight Zone, and on those series, the various “TV plays” were frequently of all manner of genres and tones, with each week providing a new look at a particular story or issue facing the nation. These programs made up the so-called Golden Age of Television, and many of them (filmed in kinescopes) have been lost to history. At the time, however, the programs were reviewed diligently in major newspapers, episode by episode, with each new “play” treated as a major work of art. And the shows were so popular because it was never immediately obvious what would happen on the next week’s episode. Sure, there were shows with continuing characters—Gunsmoke was probably the biggest drama hit of the period—but the acclaimed shows, the Mad Mens of their time, were the anthology dramas.

And yet The Twilight Zone stands as one of the last successful shows of this type. (The few that would last more than a season after Zone’s initial run are all science fiction, fantasy, or horror series, so strong was Zone’s hold on the American pop-cultural imagination.) Especially in its first season, the series wanted to tell mostly stories with a heavy genre-leaning, yes, but it also wanted to tell all kinds of stories in that regard. And that meant that a relatively dark, stark existential thriller like “Where Is Everybody?” could be followed up by a broad, goofy fairy tale like “One For The Angels.” And that kind of tonal shift was already losing its cachet with American audiences, who were moving on to comedies and dramas with continuing characters, shows where audiences could theoretically get to know characters better and better. But even if Twilight Zone couldn’t stick the landing on episodes like this, the idea that every episode could feature something wildly different, something wildly unexpected, was one that would stick around for decades after, one that would eventually find its fullest flowering in the serialized dramas we enjoy today.

Grade: C+

What A Twist!: The deal Lou struck with Death is fulfilled when he makes the “pitch for the angels” to Death himself, thus meaning that Lou moves on to Heaven, while the little girl gets to live.

Stray observations:

- Lest I sound like a total crankypants, I did enjoy the various toy robots that popped up here and there in the episode.

- I also like some of the precision of the fairy-tale plotting, like how the doctor tells the girl’s mother that they’ll know if she’ll survive right at midnight. How could he know this? Who knows! But it works for what’s effectively a little folk tale.

- Honestly, those are some ugly-ass ties Lou tries to pawn off on Death.

Next week: Zack visits a Western and a Sunset Boulevard homage with “Mr. Denton On Doomsday” and “The Sixteen-Millimeter Shrine.”