It’s a quietly chilling scene made all the more tense when Andrew plays it off like nothing to Ronnie, but it’s also an insight into one of the show’s more intriguing thematic explorations: the violence of capitalism and its effect on our identity. In the early episodes especially, the show seems to revel in the lavishness of its setting while contrasting that sense of fullness with Andrew’s persistent change in identity. The very first scene of the premiere sees the camera moving from the expanse of the ocean to the expanse of Gianni Versace’s mansion, both settings turbulent, overwhelming, and unpredictable in their own ways. Ryan Murphy directs the opening sequence in a way that immediately situates us in this world of opulence. We take in the clouds painted on the bedroom ceiling, a verisimilitude of the outdoors, and the first of many images that look to replicate an authentic experience.

Through the halls of the mansion we go, our eyes unable to keep up with everything in our path: chandeliers, priceless art, silk pajamas, and balconies with an ocean view. This is the life we are meant to envy, the American Dream come true. Murphy, for the most part, films the scene with a bird’s-eye view, as if we’re outsiders that long to be given access to these gilded halls. Immediately the show is drawing a visual connection between violence and materialism. The episode cuts from Andrew angrily screaming in the tempestuous ocean to Gianni, surrounded by servants, enjoying a lavish breakfast inside the sunlit concourse of his home. More viscerally, there’s the image of Andrew pulling The Man Who Was Vogue, a book about the rise of Condé Nast and his influence on cultural gatekeeping and style, out of his backpack, followed immediately by a gun. Violence follows materialism is the suggestion, one that pops up again and again throughout the season.

Cunanan—it’s important to note that throughout this piece any mention or analysis of Andrew Cunanan is referring to the character within this show, and not the real man he’s based on—is an enigma similar to Patrick Bateman, a character from a more problematic work that, nonetheless, still draws a connection between Bateman’s bloody outbursts and his need to conform to an ever-shifting set of ideals about what it means to be respected, glorified, and envied. There’s a reason the business-card scene in Mary Harron’s 2000 adaptation of American Psycho stands out so vividly within the film; because it provides terrifying insight into Patrick’s mind-set that the violent acts simply don’t. We need that context of Patrick’s insecurity to understand the violence.

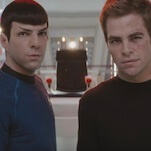

Assassination wants us to understand Andrew in a similar way. He’s a man with no single identity—Andrew’s sexuality is a major component of his complex identity within the show, and Paste’s Matt Brennan wrote a stirring piece about it—but rather a collection of signifiers meant to convey worldliness, taste, and stature. When he first meets Gianni in a club, he regales him with stories about his lavish lifestyle and impeccable taste. Only later do we, and Gianni, realize that it’s all a fabrication, an attempt to convey a certain social standing that he’s been unable to achieve.

This is the anxiety and alienation that capitalism thrives on. It’s a system that creates and then benefits from identity crisis. Alienation is a term in Marxist theory with many different meanings that, when taken together, give us a broader understanding of a feeling that’s often difficult to define. As David Harvey lays out in Seventeen Contradictions And The End Of Capitalism, one such definition is alienation as a “passive psychological term” that means to “become isolated and estranged from some valued connectivity.” The result of that alienation is “to be angry and hostile at feeling oppressed, deprived or dispossessed and to act out that anger and hostility, lashing out sometimes without any clear definitive reason or rational target.” Andrew cannot fill that void inside of him, the one created by a system that tells you that you alone aren’t good enough. When a man in a dance club asks Andrew what he does, he responds thusly: “I’m a serial killer, I’m a banker, I’m a stockbroker, a paperback writer, I’m a cop, I’m a naval officer,” and more, listing off one profession after another. He’s everything and nothing all at once, driving home the idea that under capitalism there is no true identity, only a series of labels that oppress us.

The question is, then, are we all as psychopathic as Andrew Cunanan? Certainly most of us aren’t murderers, but Assassination does seem to suggest that Andrew’s troubling need to be everything all at once is not too far removed from our own need to belong, a feeling amplified in our current culture of constant sharing and liking. We curate our lives, and more importantly our social media timelines, in much the same way Andrew curates his behavior and personality. Andrew literally puts on a costume, another man’s suit and his expensive watch, to attend the opera. He can’t imagine doing anything else. He tells outlandish stories about fictional past boyfriends; one in particular would drive him around in his Rolls-Royce and also snagged Andrew a job building sets for Titanic. These are small violences, little bits of untruth that erode the social fabric and Andrew’s own understanding of himself. Are we doing the same? Are we allowing Instagram influencers, native advertising, and increasingly “hip and socially aware” brands to make us feel like shit just so we’ll buy the thing they’re shilling that supposedly won’t make us feel that way?

Assassination, in at least some way, wants us to ask those questions. It’s not the larger thematic thrust of the season, but it is an intriguing and unavoidable presence. The series asks us to question our own search for identity through material means by showing not only how Andrew is affected by alienation, but also how those around him struggle within a capitalist system. The Miglins are the best example. They are the epitome of the American Dream under capitalism. At a fundraiser gala, Lee gives a speech that evokes the classic “bootstraps” story of his success, and his wife has no trouble building a line of perfume to sell on TV. Everything is picture perfect.

That is, until you dig deeper. At home, Marilyn Miglin (Judith Light in a devastating performance) takes off her makeup, a maudlin look on her face. The mask necessitated by the public gala has been removed, and her sorrow is now visible. Similarly, Lee Miglin can’t be his true self, a gay man in a world that would financially and socially punish him for his sexuality. He wishes he could just “roam among them,” a beautiful statement about wanting to live free of restriction and punishment for who he is. But capitalism has a set of rules and an oppressive structure that must be abided by, and anything outside of that is pushed aside. So, this isn’t just about Andrew, but rather all of us, and the way we’re forced to imitate ways of life rather than living the way we truly want to.

I wish there were a hopeful message to end on, something in the show that points the way forward to a place where we can know one another’s intentions and understand our own, free from the forces of capitalism. But if anything, the world portrayed in The Assassination Of Gianni Versace, in all its gold-plated, vacuum-sealed glory, has only gotten worse. We’ve become more convinced that we can buy something in order to be something. We’ve become chameleons of emotion, projecting our grief, joy, and anxiety to our followers without any check on our authenticity. Like Andrew, we can wear any mask we want.

As chilling as the duct-tape scene is, the most telling moment when it comes to the performative nature of Andrew Cunanan, and thus ourselves, is when Andrew sees the news’ first piece about the killing of Gianni Versace. His face is blank for a moment before he’s overcome with grief. He looks on the verge of weeping, all before the hint of a smile creeps in and the episode cuts to commercial. An imitation of emotion, literally mimicking the public grief of the woman in front of him, as convincing as the real thing. It’s a moment with implications that the show explores throughout the season, which is that Andrew, and everyone else, is a product of a system that grinds us down, asks us to perform emotions and wants, and then shames us for failure. “It was all a lie, an act,” says David, one of Andrew’s victims, moments before he gets a bullet in the back. The violence of capitalism breeds an identity crisis, and a subsequent emptiness and isolation, that can lead to physical violence. We’re all at risk, refusing to challenge the rules and upend the system. We have more in common with Andrew Cunanan than any of us would like to admit.