Amy’s bedroom is full of beautifully strange and disturbing art that combines childish artifacts with a sort of grotesque sexuality—felt penises, a tiny fetal Hitler—but her naked body costumes are where she draws her power. She wears the male one out in the woods, or occasionally under her clothes, as when she whips out her penis in a cemetery with her friend. Like her reckless behavior and scatological sense of humor, it’s a defense mechanism, and a way for Amy to co-opt the misogyny that surrounds her. Eventually, though, she meets a guy who is patient enough to wait for her to let down her hackles. Kenny (Kentucker Audley) seems like a nice guy, but unfortunately for everyone involved, seems is the operative word.

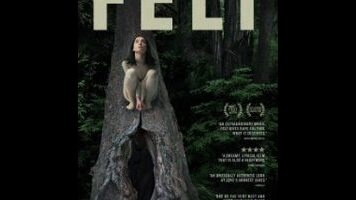

At first, Felt doesn’t feel substantial. There doesn’t seem to be much of a plot, or even a necessarily linear narrative. Amy’s nightmares leak into daytime, and the film follows that same dream logic. It can be as frustrating to watch Amy (and the movie) spin out as it is for her friends to experience. But what anchors the movie is co-writer and star Amy Everson’s performance. Everson is endlessly watchable as she cycles through despair, anger, wariness, and trust. Her sense of humor as an artist and performer shines through, especially in one scene where she answers an ad for semi-nude models by showing up in a nylon suit with a protruding vulva. She and the other model, played by Roxanne Knouse, have a great time teasing the hipster photographer (played by hipster photographer Merkley) by giggling, farting, and rubbing their butts on his hotel room pillows. The sight of Amy in her naked man suit, complete with a lifelike penis and cloth scrotum, is somehow more vulnerable and revealing than if she were completely nude.

Far too many movies rely on rape as a lazy character-development device or a way to shock the viewer. Felt assiduously avoids that; although there are indications everywhere that Amy’s trauma is sexual in nature, it’s never stated outright. Co-writer and director Jason Banker’s use of handheld cameras and abrupt edits makes the viewer feel physically uncomfortable, but it’s his collaboration with Everson that’s stunning. Although she’s billed as a co-writer, the project was developed with her after Banker took an interest in her art, specifically her costumes; the director’s previous feature, Toad Road, was similarly developed with its leads as a sort of hybrid feature/documentary. Of course, it’s not necessary to know all that to appreciate this film’s power. Although there are a few moments that feel a little too on the nose, Felt sneaks up on you and lingers for hours afterward.