The Walk takes its time getting to the crime, but it’s worth the wait

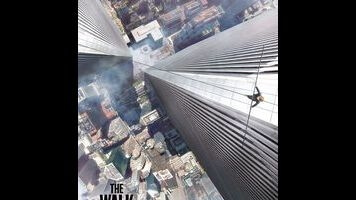

For years, all we’ve had are the pictures—spectacular still images of the man on the wire, walking fearlessly between the peaks of two skyscrapers, a pole in his arms, a gaping abyss at his feet. They’ve been enough, frankly, to secure a spot in the collective imagination for Philippe Petit, the French aerialist who turned the World Trade Center into his high-altitude stage. Who needs a phony dramatization when photographic evidence of the real deal is a mouse-click away? Yet The Walk, the latest feat of technological wizardry from Robert Zemeckis, does more than simply send Petit’s death-defying stunt into motion. It puts audiences up there on that thin cable with him, letting them see the world as he saw it, from 100 stories up. Every groan and sway of the wire registers. The depth of the mighty drop is overwhelming. And it’s easy to believe again in the sheer enormity of the Twin Towers, resurrected from scratch by the director of Back To The Future and Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

Of course, most of The Walk is pure prelude, 80 minutes of time killing until Petit takes that first momentous step off the edge of the south tower. (They might well have called it The Wait.) Such delayed satisfaction is not incompatible with the thematic thrust of the material; Zemeckis and his co-writer, Christopher Browne, float the idea that Petit’s whole life was a long build to this single majestic moment. Even still, there’s a bit too much Gumpian whimsy to the movie’s first half, which chronicles the salad days of this famous wire-walker (played, with an exaggerated French accent but credible physicality, by Joseph Gordon-Levitt). Perched on the peak of the Statue Of Liberty, the towers visible behind him, Petit breaks the fourth wall to narrate his own adventures, including his tutelage under tough-love mentor Papa Rudy (Ben Kingsley, in Hugo mode) and his courtship of fellow street performer Annie Allix (Charlotte Le Bon).

The Walk probably wouldn’t exist were it not for Man On Wire, the Oscar-winning documentary on Petit’s triumphant performance. Those who have seen the earlier film will struggle not to catalog the ways that the new one deviates, especially as many of the anecdotes have been recycled. Zemeckis, a showman in his own right, seems intoxicated by the artistic ambitions of his subject—so much so that he can’t help but gloss over some of the less flattering aspects of Petit’s personality. (As played by JGL, he’s more of an occasionally stubborn dreamer than the megalomaniac described by the talking heads of Man On Wire.) Since The Walk is technically based on Petit’s own memoir, To Reach The Clouds, it’s not surprising that it ends up marginalizing his accomplices. Those characters that aren’t shuttled off to the sidelines, as Le Bon’s love interest basically is, are reduced to caricatures, the most egregious of which is probably a perpetually baked late-hire (Benedict Samuel) who speaks almost exclusively in clichéd pothead lingo.

It was perhaps inevitable, given the subject matter, that The Walk was going to dually function as a valentine to the Twin Towers. (A dozen years removed from the days when filmmakers were respectfully, digitally removing them from skyline shots, we now have a blockbuster that uses CGI to erect them anew.) Zemeckis, a gooey crowd-pleaser at heart, overplays the hushed reverence at times, using heavy-handed dialogue to suggest that it was Petit’s audacious walk that “brought them to life” for many New Yorkers (the towers were famously derided as giant filing cabinets upon construction) and closing on a final shot better suited to a postage stamp than a movie. These sentimental gestures, inflated to IMAX proportions through the overbearing swell of Alan Silvestri’s score, feel harmless but unnecessary: There’s more than enough poignancy in simply seeing the grand structures recreated with such loving, meticulous care.

To that end, The Walk doesn’t find its footing until it arrives upon that fateful date in 1974 and relocates to the World Trade Center, effectively transforming from a corner-cutting biopic into a tense, procedural heist picture. The “coup,” as Petit called it, is plenty thrilling on its own; seeing these men infiltrate the building, talk their way to the top, and race against the clock to get the wire in place is the stuff of first-rate popcorn entertainment. (One irresistible touch: The accomplice with him on the roof is terrified of heights.) But it’s when the walk portion of The Walk arrives that this unevenly scripted, fact-based thriller achieves its full potential. Even without the suspense of uncertainty, the sequence achieves a bated-breath intensity and wonder. It’s a true marvel of vertigo-inducing special effects, with Zemeckis employing photorealistic technique to create a sprawling metropolitan void and finding a rare essential use for 3-D—namely, to stretch and expand the depth of field, making us feel every foot separating Petit from the street far below. Good luck getting the same sensation from a still image, real or not.