The Way He Looks sacrifices the woods for the trees

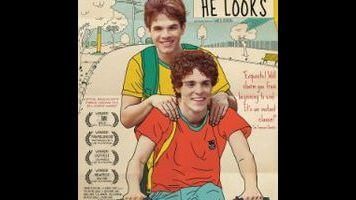

It’s easy to label director Daniel Ribeiro’s queer-themed feature debut (Brazil’s official submission for Best Foreign Language Film to the 2015 Academy Awards) as a “sweet nothing,” so tender are its intentions and so fleeting its overall effect. Yet the movie’s overarching compassion does count for a lot. Leonardo (Ghilherme Lobo) is a blind São Paulo teenager going through many of the usual growing pains (he’s dreaming of his first kiss) and several others unique to his disability. Bullies at school tease him about the clacking assistive typewriter he uses in class, and his parents, his mother especially, are overprotective to the point of exasperation. (Even asking permission to go on a supervised field trip is a production.) All told, though, Leonardo is pretty well adjusted, in large part thanks to his best friend, Giovana (Tess Amorim), who’s always there to lend a literal and figurative hand. But then handsome new kid Gabriel (Fabio Audi) enters the picture, quickly befriending Leonardo and stirring both his and Giovana’s adolescent emotions.

There are so many cheap and hokey ways this love triangle could play out that it’s almost a relief Ribeiro (expanding his own 2010 short film I Don’t Want To Go Back Alone) keeps things consistently tranquil. Situations that would be treated histrionically in many movies (like the young protagonist’s unwitting confession to Giovana that he’s in love with Gabriel) are passed over with relative placidity—a ripple as opposed to a tidal wave. The Way He Looks’ tone complements the easygoing Leonardo, who loves classical music (Arvo Pärt’s overused “Spiegel Im Spiegel” gets cued up twice) and even flips the bird at his tormentors with an endearing gentleness. The film’s idea of stirring the pot is having Gabriel introduce his Handel-loving new buddy to the work of Belle & Sebastian.

As far as queer coming-of-age first features go, The Way He Looks doesn’t hold a candle to Ira Sachs’ The Delta or Patric Chiha’s Domaine, both of which churn with youthful fervor. Here, there’s never any doubt Leonardo will make it through the pre-adult gauntlet fully intact, so the narrative has a wispy, anti-dramatic quality, almost as if Ribeiro is so focused on making all the little details ring true that he’s ignoring the larger picture. Nonetheless, those small moments are often quite beautiful, like the empathetic way the writer-director introduces his lead character’s blindness—focusing on the young man’s momentary distress after Giovana dives underwater in a pool and doesn’t answer him—or the incisive scene in which Leonardo puts on Gabriel’s hoodie, smelling it and caressing it as if it had talismanic powers. Ribeiro captures the experiential awkwardness of young love pitch-perfectly. (A terrific party scene brims with shuffle-’round-the-dance-floor gawkiness.) Would that he could wrangle it all together into something that truly sang and touched the soul.