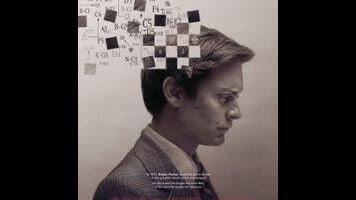

Viewers unfamiliar with the American chess champion Bobby Fischer might be forgiven for assuming, based on the casting of Tobey Maguire as a 30-ish Fischer in Pawn Sacrifice, that his genius was of the quiet, withdrawn variety. But while this movie version of Fischer does indeed suffer from mental health issues that make it difficult for him to form functional human relationships, one of the film’s strongest, most potentially surprising pleasures is the sight of Maguire playing both with and against his usual type. While this Fischer is a chess prodigy who spends a lot of time in his own head, easily distracted by bursts of life’s background noises, he also has a mouthy pro-athlete bravado that seems consistent with his Brooklyn upbringing. That attitude gives Maguire the opportunity to play a little meaner and wilder, reminiscent of his underrated work in Spider-Man 3 and The Good German (as a far less villainous character than he plays in either of those).

His braggadocio recalls an overgrown child, with his casual dismissals of other chess players and antsy, loosey-goosey body language linking to his childhood impatience with waiting for his opponents’ moves. Maguire’s overgrown-boy look creates continuity between the younger versions of Fischer the movie shows before spending most of its time with the adult version in the ’60s and ’70s, leading up to a series of 1972 matches with Russian chess master Boris Spassky (Liev Schreiber, in a performance of relatively few lines and even fewer in English). Fischer’s mental problems and frequent encounters with Russians make him a perfect victim of Cold War paranoia, and he’s often convinced that he’s being followed and bugged. He may not be right (and his ranting against the commies and “the Jews” seems especially disturbed when other characters point out that he is, in fact, Jewish), but the methods aren’t unthinkable—and his trusty lawyer Paul Marshall (Michael Stuhlbarg) really is in contact with people in Washington, who see Fischer’s chess matches with the Russians as the rare winnable conflict with communists.

It’s interesting material, especially when Fischer is sequestered with Marshall and his sort-of coach, Father Bill Lombardy (Peter Sarsgaard). The movie falters, though, when it tries to jazz up its historical context, with director Edward Zwick working overtime to express Fischer’s interior and exterior worlds cinematically. From a very early scene where he cuts to various sources of noise in Fischer’s childhood bedroom before dramatically racking focus on his trusty, soothing chess set, Zwick wields his visuals with enthusiastic bluntness, like a teacher convinced he’s bringing history to life by dressing up in a crazy costume. He cuts to archival footage, shots made to look like archival footage, cheesy quasi-surveillance shots, and plenty of slow-mo portents; little of it has the intended zing. The film’s most expressive visual moments are less showy: A static shot of his lawyer and coach in a hotel lobby, with Fischer pacing in and out of the frame as he complains about its shabbiness, conveys plenty about the trio’s relationship. Later, Zwick and editor Steven Rosenblum make a succinct (and funny) cut from the very beginning of a Fischer match to a shot of his opponent in a car, heading home, obviously defeated.

Many of the chess matches are kept partially or entirely off screen; Pawn Sacrifice is largely about prep work, about Fischer’s endless psyche-up in the face of decreasing mental stability. When he gets nervous or agitated, he makes more demands and changes the terms of his deal; when he manages to actually begin a game, it feels like a major victory. When the time does come for the dramatization of the chess matches between Fischer and Spassky, the movie struggles to wring much drama past the first few games—understandable, really, for a 24-game series. Pawn Sacrifice also comes with a long, unwieldy postscript that covers the last 35 years or so of Fischer’s life, avoiding some biopic pitfalls by simply screeching to a halt and explaining the rest on screen. It’s a fitfully entertaining and well-acted movie that doesn’t quite come together—though maybe the frustrating lack of resolve is appropriate for Fischer’s arc-resistant life.