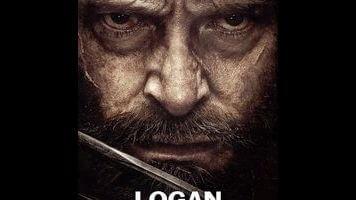

The Wolverine series gets a superb sendoff with the brutal, R-rated Logan

Wolverine uses his claws in Logan. He uses them the way that fans have always dreamed he might, the way the movies and certainly the cartoons and even the comics have never entirely allowed. They’ve always been a little ornamental, Wolverine’s claws: three per hand, harder than steel, sharper than diamond, but usually sheathed before they can do real damage. When the gruffest, toughest, and most Canadian of the mutants does cut loose, as in the show-stopping mansion rampage of the second X-Men movie, it’s cleaner than it really would or should be: Blades go in, blood doesn’t come out. But there’s nothing clean about what Wolverine does with his claws this time around. His knuckle sandwiches leave stumps, stains, and a body count.

One year after Deadpool pushed the limits of extremity in an X-Men movie, Logan pushes them further. By the end of the opening scene, in which some very dumb carjackers mess with the wrong furry loner, you know why this third and supposedly final entry in the solo Wolverine franchise has been handed an R rating. It went looking for one. The language is blue (the very first line, spoken by our aged antihero himself: “Fuck”) and the violence is red, with limbs hacked off and faces skewered. Logan is as brutal and bleak as any superhero movie in recent memory; they could have called this one X-Men: Apocalypse. But it’s also a comic-book adaptation that takes its characters and its themes seriously, that elevates the genre past spectacle and on to something resembling art, even poetry. It’s adult in more ways than one.

Set in 2029, when mutants have all but gone extinct, Logan presents a future America that’s closer to a cruddy Cormac McCarthy version of our here and now than the sunless dystopian wasteland of Days Of Future Past. (Call it a very significant accident that the film’s foolish, cruel villain happens to be named Donald.) When not working as a chauffeur for bellowing business bros and squealing sorority girls, Logan (Hugh Jackman, rocking the CGI claws for what he insists will be the final time) lays low in a junkyard desert headquarters just south of the border, where he looks after an elderly, ailing Professor Xavier (Patrick Stewart). Xavier, now in his 90s, is losing his mind—a dementia that manifests itself through deadly, occasional mental shockwaves that paralyze everyone in proximity. Wolverine isn’t doing much better; poisoned by the Adamantium that coats his skeleton, he’s finally looking and feeling close to his age, that trusty healing factor slowing by the day.

Retired from the do-gooder business (“The Statue Of Liberty was a long time ago,” he tells Xavier, in a reference that carries a timely import), Logan ends up serving as reluctant guardian, mentor, and protector to Laura (Dafne Keen), a young mutant on the run from a heavily armed task force. Writers have been placing Wolverine into this kind of Lone Wolf And Cub relationship for years, but Laura is more of a miniature version of her father figure—claws and temper and all—than a Shadowcat or a Jubilee or Anna Paquin’s Rogue. Crisscrossing the Southwest en route to a mutant-sheltering haven that may or may not even exist, the two tag team waves of pursuing cavalry, in some of the bloodiest superhero combat since Guillermo Del Toro made a Blade sequel. This is the first X-Men movie that doesn’t bottom out with endless, expensive scenes of actors hurling CGI effects at each other. It’s also the first X-Men movie that can be called leisurely, even minimalist.

In truth, Logan is more of its own thing: a sorrowful outlaw road movie in superhero drag. The previous film in the series, The Wolverine, drew loose inspiration from the original 1982 Wolverine miniseries by Chris Claremont and Frank Miller. Here, returning director James Mangold and his co-writers, Scott Frank and Michael Green, borrow elements from Mark Millar’s “Old Man Logan” storyline, chasing an Eastern adventure with a prototypically Western one: In case horses, a farmstead, and Jackman looking strikingly like a young Clint Eastwood didn’t make the genre parallels clear enough, Logan cuts to Shane on a television set. Mangold, who directed the 3:10 To Yuma remake, understands Wolverine as the most mythic of Marvel’s A-listers—a ronin with built-in blades, a gunslinger with talons instead of pistols—while also grasping again the need to make him less than indestructible, to give the one-time Weapon X some physical and psychological vulnerability. At a time when both Marvel and DC are investing in their multi-year crossover plans, Mangold also appreciates the merits of standalone storytelling; Logan leaves its franchise history almost completely implied, resisting callbacks and cameos at every turn.

Like Wyatt Earp or Jesse James, Wolverine has lived long enough to see his checkered past transformed into tall tales; in another smart link to Western tradition, he’s confronted with his own legend, splashed across the panels of gas-station comic books. Close to the Unforgiven of superhero cinema, Logan builds its simple, cross-country narrative around regret, pitting Wolverine against his legacy of bloodshed—metaphysically, in one nightmarish case. This theme, like most others, remains largely unspoken, conveyed mostly through the grizzled gravity of Jackman’s performance, which carries the full weight of the character’s eight other big-screen appearances. (At this point, its hard to believe that there was a time when his casting was met with skepticism—when anyone thought he was too tall or too suave for the role he’s made his own.) Logan, in general, boasts some of the best acting of its genre, from Stewart’s wounding turn as a wizened Xavier, haunted by his own regrets, to the bit players the film’s trio of travelers encounter along the way. This is fortunate, because the movie often plays closer to character study than anything else; for every gruesome showdown, there’s a quiet conversation in the cabin of a pick-up truck or a makeshift graveyard in a one-horse town.

Those who think comic-book movies have gotten too serious for their own good will likely find more to object to in Logan, which is about as grimly poker-faced as Deadpool was irreverent. By the end, the carnage has become almost surreal in its intensity: There’s only so many times that you can watch someone get their skull punctured by pointy hand daggers before you start feeling a little numb to it. But the movie’s fatalism never quite shades into Snyderesque nihilism; the core X-Men principles of hope, inclusion, family, and generational torch-passing animate even its grisliest passages, until a final scene (and final image) that shines a beacon of faint light through the darkness. What’s special about Logan is that it manages to deliver the visceral goods, all the hardcore Wolverine action its fans could desire, while still functioning as a surprisingly thoughtful, even poignant drama—a terrific movie, no “comic-book” qualifier required. Yes, Wolverine finally goes berserk with those claws. But it may be the moments where he doesn’t that cut deepest.