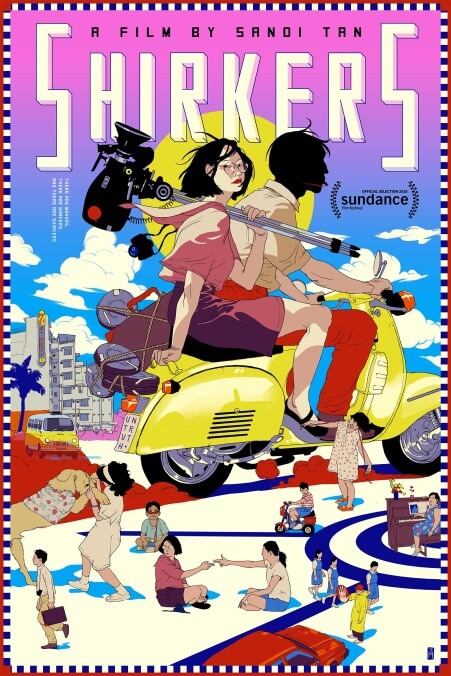

The wonderful Shirkers reclaims a lost film by chronicling its rollicking DIY production

The do-it-yourself ethic that drove numerous underground artists in the tail end of the 20th century had as much to do with determination as it did with self-sufficiency. Though certainly ideological—especially in an anti-corporate 1980s punk context—and often financially necessitated, DIY was still rooted in the uncompromising belief in making something by any means necessary. For budding artists everywhere, particularly those who grew up geographically and politically alienated, what was inspiring was not just that personal art could come from anyone and anywhere, but that it could actually reach other weird souls who would in turn pay it forward. Creativity begets creativity when it ceases to feel impossible.

This was the cultural context that allowed someone like Sandi Tan to thrive. Growing up in Singapore in the 1980s, she and her childhood friend Jasmine Ng found themselves in independent films and music of the era, often acquired through clandestine means, e.g., a makeshift videotaping syndicate that brought them Blue Velvet. They immersed themselves in Singapore’s underground zine culture (eventually creating their own, The Exploding Cat, that had international reach) and shined a light on their own marginalized personalities, all while they were still teenagers. In a part of the world in which cultural access was extremely limited, Tan and Ng became anti-establishment pioneers hell-bent on bringing “alternative” voices to the forefront.

Their rabid cinephilia led them to a filmmaking workshop where they made a new friend, Sophia Siddique Harvey, and met the enigmatic teacher Georges Cardona. By 1992, Tan had devised a plan to make her own independent road film, Shirkers, to be shot on the streets of Singapore with a merry band of collaborators and directed by Cardona. Inspired by the French New Wave and ’80s indie film (Jarmusch, Wenders, Lynch, the Coens, etc.), Shirkers was to be Singapore’s first foray into a new type of national cinema, one informed by global youth culture and guerilla-style practices, and which might have created a modern filmmaking infrastructure. When their sprawling, shoestring production wrapped at the end of the summer, Tan and her friends returned to college, leaving the raw material with Cardona to be processed and edited. Unfortunately, he absconded with the footage, never to be seen again.

Tan’s documentary Shirkers attempts to reclaim their lost film by channeling the DIY spirit of the original production, while chronicling how it came to fruition and its tragic disappearance. Employing recovered footage from the original shoot, discovered over 20 years after the fact, as well as collages of handmade materials from the era, Shirkers situates the audience within the youthful, infectious environment that facilitated such a film in the first place. Tan reflects on that period in her life with her partners in crime, Ng and Harvey, all of whom marvel at their own gumption but cringe at their innate trust in Cardona, a sociopathic con man who disguised himself as a mentor. Their production anecdotes are as funny as they are moving, demonstrating a single-minded faith in their bizarre, imaginative vision. With Shirkers, Tan doesn’t indulge in nostalgia, but rather evokes an un-calculated, offbeat sensibility that feels distant from our current algorithmic-driven culture. The palpable irony of Shirkers being released on Netflix cannot be overstated.

Tan’s documentary formally resembles one of her Exploding Cat zines from the late ’80s, befitting the original Shirkers’ raw, homespun craft. Co-edited by Tan, Shirkers uses the limited 1992 footage to wonderful ends, equally disorienting and compelling viewers with out-of-context scenes. Tan seamlessly cuts between archival materials and new talking head interviews to create a collapsed temporal framework: Shirkers lives on through its participants even though the finished work can never truly exist. The Shirkers documentary in turn functions as a reckoning with how that lost film destroyed the innocence of its young creators, even though it was that innocence that enabled its existence.

There’s a structural absence here, and it takes the form of Georges Cardona, a man who gave the three women in his charge the confidence to make Shirkers but then stole it out from under them for vague, cruel reasons. Tan willfully admits falling under Cardona’s spell, not least of which because his fabulous origin story parallels the movies they both worshipped; he’s someone who lied not just about his age but also how he was the inspiration for James Spader’s voyeuristic character in Sex, Lies, And Videotape. Ng and Harvey remind Tan that they both resented Cardona’s arrogance and disorganized production practices, going so far as to record their misgivings in a production diary, but put up with it for the good of the film, something they clearly regret. The second half of Shirkers involves Tan traveling to Cardona’s hometown of New Orleans to determine why he would commit such a blatant act of creative treason, and yet the film never becomes about him. In fact, Shirkers is an attempt to reclaim the film from Cardona, taking the story out of his hands and re-centering it on the women who made it.

Shirkers isn’t without its flaws: Tan’s NPR-style voice-over narration can be a liability, often straining for meaning in heavy-handed ways, and the film tends to needlessly explicate potent subtext that would best be left unaddressed. Yet these blemishes can’t help but feel quaint in the face of such an achievement. With Shirkers, Tan crafts a conflicted punk memoir, mourning the loss of her original feature but celebrating its ingenuity, bemoaning her toxic relationship with Cardona while commemorating the close bonds she forged with Ng and Harvey. It’s powerful that the end credits also list the full cast and crew of the original production, cementing their work on record for the first time in 25 years, all but ensuring they will no longer be forgotten. The original Shirkers might be a product of a bygone era of pop culture, but its new nonfiction form scans as a second attempt to reach those fellow weirdos who are desperate to make something real, established structures be damned.