The writer-director of The Savages takes on an awkward subject in Private Life

The main characters of Tamara Jenkins’ Private Life, Rachel (Kathryn Hahn) and Richard (Paul Giamatti), are a fortysomething Manhattan couple who have spent a small fortune trying to have a baby—an obsession that their friends and relations liken to an addiction. She is a novelist who put off having kids for too long so she could focus on her writing; he used to be a theater director, but now sells pickles. They’ve had bad luck with adoption agencies and fertility clinics, but they keep trying. Like compulsive gamblers, they borrow money from Richard’s brother, Charlie (John Carroll Lynch), a successful periodontist who lives outside the city, for treatments with a low-single-digit rate of success. Of all the passed opportunities in their lives, parenthood is the last one they can’t let go. Whether they really want to be parents remains an open question.

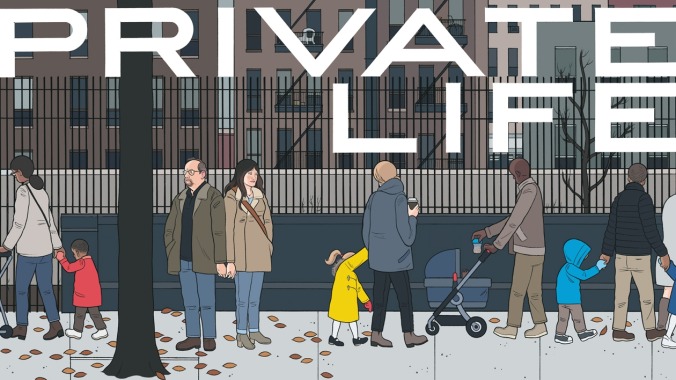

Of course, we, the hip moviegoers and Netflix viewers, are so tired of seeing lit-influenced movies about these artsy, potluck-dinner-party New Yorkers who make Baumbachian references to ’70s films mid-argument and are crushingly aware of the first-world-ness of their problems. But the truth is that a realistic version of this story set in the unrugged, suburbanized part of Middle America, where people drive to get coffee and everything is unaccountably big, would mostly take place in cars. The city gives the title its implied irony: Whether it’s in a cab, a restaurant, a clinic’s packed waiting room, or in a bedroom that’s right below one’s loud, hard-partying younger neighbors, there is not much about urban life that is objectively private.

Jenkins (whose last feature, The Savages, came out way back in 2007) plays this for cringing laughs and sight gags. In its meandering, episodic early chapters, which bear mockingly ominous titles like “The Retrieval” and “The Transfer,” Private Life moves like a comedy, going from one joke about the foibles of high-strung Manhattanites to the next. But there’s something, too, about the layouts of book-filled, rent-stabilized apartments that gooses the inherent voyeurism of domestic dramas; at the very least, it gives us an opportunity to judge characters by their reading material (Richard is making his way through Knausgård and putting off Tom Wolfe) and record collections. Into this environment of winking references to autofiction and Me Decade self-indulgence comes Charlie’s immature, mid-twentysomething stepdaughter, Sadie (Kayli Carter). She wants to be a writer, and has always looked up to Rachel and Richard as real-deal bohemians—the “cool” aunt and uncle who really get her and are nothing like her overbearing, Eileen Fisher-wearing mom (Molly Shannon), who’s having her own crisis of identity with menopause.

But we know what they really are—a neurotic folie à deux held together by mutual unfulfillment and the sunk-cost fallacy. They have their own motives for taking Sadie in on a moment’s notice when she decides to once again drop out of college: They need a donor egg. At 127 minutes, Private Life can’t be accused of rushing; it takes its time getting Sadie into Rachel and Richard’s apartment. But before long, she is sucked into their life: the drugs; the tests; the message-board buzzwords; the crushingly dull hours spent at the clinic of their ineffectual, prog-loving fertility specialist, Dr. Dordick (Denis O’Hare).

Jenkins directs on a scene-by-scene, setup-and-punchline basis; both the overall structure of Private Life and its caustic characterizations can be shaky, and its implicit lesson about the hard truth of parenthood—namely, that one can unwittingly pass on their anxieties—ends up buried. But in its busy closing stretch, there is a fine group portrait of characters coming to terms with the difference between what they might never be and what they can be for each other.