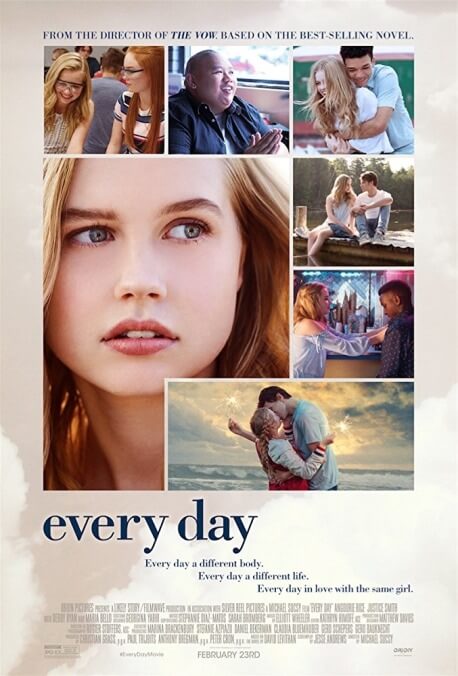

There are seemingly insurmountable obstacles to a romantic relationship, and then there’s waking up in a different body each morning, a “person” unrooted to any particular physical presence. A, the lead character of David Levithan’s novel Every Day, has this lifelong condition. For 24 hours at a time, A Quantum Leaps into a body that shares his (or her) general age and vague geographical area, but little else. A never wakes up in the same body twice, and attempts to leave little evidence of the brief replacement for the body’s rightful owner to discover. Memories of A’s actions can linger somewhere in the host body’s brain, like a dream or a blur, but any attachments A forms are ripped away at midnight.

The next morning, the movie shows Amy (Jeni Ross) completing the same morning routine as Justin (setting phone alarms, examining her face in selfie mode). Amy, claiming to be a potential transfer student, finds Rhiannon at school. The day after that, a skinny boy named Nathan (Lucas Jade Zumann) tracks her down at a house party; later, she meets up with a character played by Jacob Batalon from Spider-Man: Homecoming, and so on. Eventually, A directly explains the logistics of his body-hopping, and Rhiannon’s skepticism gives way to absorption into her new friend’s routine, watching her phone for texts from unfamiliar numbers, driving around to pick up people who look like strangers, and following A’s semi-secret Instagram account (an invention for the movie, and a savvy one).

Against ridiculous odds, A and Rhiannon form a romantic relationship, helped along by the movie only occasionally throwing A into a body that doesn’t belong to a handsome teenage boy (Rhiannon seems to be heterosexual, if open-minded) and never giving poor Justin a shot at redemption for his douche-y behavior. It’s hard to blame the movie for a little fudging. In Every Day’s translation to the screen, it gets to drop Levithan’s sometimes overwrought emo-prose, but it also loses his ability to burrow into this strange character’s head. In place of that close point of view, the movie asks for near-impossible performance continuity between a dozen or more different young actors playing A on different days; they do their best to give a sense of the non-physical person behind their eyes, but the movie necessarily shifts some attention to the consistency of Rhiannon. Rice looks something like a junior-level Amy Adams and brings a wide-eyed empathy to the part without succumbing to Miniature Adult syndrome. She looks and sounds like a kid, even when the dialogue doesn’t have the ring of adolescent truth.

There are frays like that all around the edges of Every Day, distracting from the compelling dilemma at its center. The scene-to-scene transitions are surprisingly clunky for a movie that very much depends on them, especially when they involve stock-looking overhead shots (cheap to the point of pixelation) of various generic locations. Later, when A and Rhiannon discuss the logistics of their future together, the movie offers a hypothetical flash-forward onscreen, which would be the most powerful moment in the film if Sucsy were better at conveying what, exactly, is being hypothesized through his images. Plotwise, the movie is faithful to the novel, but its eventual resolution is insubstantial and unsatisfying, as sometimes happens when story points are dutifully replicated onscreen without accompanying visuals.

The movie does stand out from a lot of YA romances. There are any number of metaphorical applications for A’s condition, some implied more strongly than others, including trans struggles, gender fluidity (“Do you consider yourself a boy or a girl?” “Yes.”), teenage desire to fit in, even accidental catfishing (A is always the same on text or the internet, and never the same in person). Every Day is sweet and sincere enough to remain open to these interpretations, but too gentle to assert itself into anything of real consequence.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.