The year he won for Cuckoo’s Nest, Jack Nicholson delivered an even better performance

Watch This offers movie recommendations inspired by new releases, premieres, current events, or occasionally just our own inscrutable whims. This week: The Academy Awards are Sunday, so we’re looking back on times when an actor was nominated for the wrong film—and on the performances they should have been nominated for the same year.

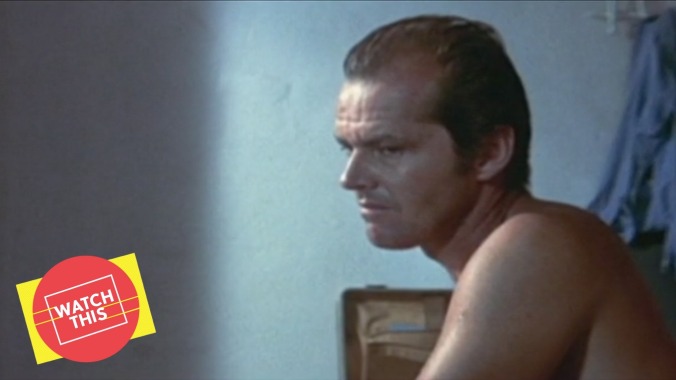

The Passenger (1975)

It’s not hard to understand why Jack Nicholson won Best Actor for his role in Milos Forman’s One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Next. By the mid-’70s, the Academy was already overdue to honor an artist who had quickly become one of the most iconic actors of his generation. What’s more, Cuckoo’s Nest is a terrific picture, an ideal pairing of performer and material, electrifying and entertaining in equal measure.

But that’s also kind of the point: Can you really picture anyone else playing McMurphy? It’s a role Nicholson was born to play, perfectly calibrated to his live-wire, movie-star magnetism. And that’s also why it’s not as impressive an achievement as his other major role that year: the lead in Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger. In Cuckoo’s Nest, all Nicholson had to be was Jack Nicholson, movie star. It wasn’t exactly a stretch. In the hands of the Italian arthouse provocateur, however, the star power disappears; in its place is a mesmerizing portrait of a man out of his depth—a situation in which Nicholson rarely found himself, either on screen or off.

His David Locke isn’t exactly a man happy with himself. Ten minutes into The Passenger, the television journalist, in northern Chad to complete a documentary, is stranded in the desert by a car that’s broken down—and Locke breaks down with it, raging in frustration and crying in futility. As we soon learn that his disenchantment runs deeper than his current predicament, straight through to his lot in life. Walking back to his hotel, Locke discovers that another guest, a wealthy world traveler named David Robertson with whom he struck up an acquaintance, has died of a heart attack. Locke makes an impulsive decision: As the two men look somewhat alike, he’ll steal Robertson’s identity and fake his own death, assuming the mysterious businessman’s life and belongings. Even after he learns Robertson was an underground arms dealer, funneling weapons to the resistance fighters in Chad’s civil war, he can’t seem to stop himself from following his dangerous itinerary, as though drawn ineluctably into the fate of the man whose life he’s stolen.

What makes Nicholson so effective in the role is the way the actor smothers his traditional confidence-man charisma, just as the character of Locke is desperately wishing he could summon the same. It’s a deeply reactive performance, as Locke becomes Robertson and slowly, cautiously starts to observe all the little elements of this enigmatic man’s life. Here’s someone so desperate to escape his home, his marriage, and his career that he throws himself into a stranger’s existence, letting friends and family alike think he’s dead, without so much as a second consideration. Yet in the film’s steady, methodical unfolding, the past is never done with Locke; any time he starts to think he can settle comfortably into his new future, another colleague or loved one turns up searching for the man he’s impersonating, hoping “David Robertson” can shed some light on Locke’s final days. It’s the ultimate irony of his gambit: By becoming the one person who can connect Locke’s life to his death, he’ll never be free of the past he tries so frantically to escape.

Antonioni lets Nicholson disrupt shot after shot, moving in and out of frame to emphasize how disjointed and fractured his character’s life is, and how even the radical act of becoming another person can’t fix that problem. Despite the gun-running subplot, the film is slowly paced and sharply focused on Locke’s impossible wanderlust, whether cluelessly following the travel plans previously made by Robertson or striking up a relationship with an equally dissatisfied architecture student (Maria Schneider). Yet the theme of alienation is brought into ever-starker relief by Antonioni’s locations, through gorgeous old international settings—Munich, London, Barcelona—whose deep roots and identities highlight the fragility of Locke’s own. By the bravura penultimate shot (one of the the great camerawork tricks of the era, so memorable that it’s often misidentified as the final shot), Antonioni has offered one of his finest explorations of a long-running obsession: Can we ever really know someone, even ourselves? It’s an idea richly underscored by Nicholson, departing from the version of himself the world had gotten to know.

Availability: The Passenger is available to purchase digitally from VUDU.