The Zolas is a beautiful critique of the relationship between creator and muse

The Zolas, the graphic novel debut for both writer Méliane Marcaggi and artist Alice Chemama, is a historical work about the relationship between a creator and his muse. The creator in question: esteemed 19th-century French writer Emile Zola—and the muse is his wife, Alexandrine Zola. Through its stunning art, which is more than worth the read, The Zolas documents how this relationship is founded on the creative instincts of the muse, but its approach to the historical record limits its intended goal.

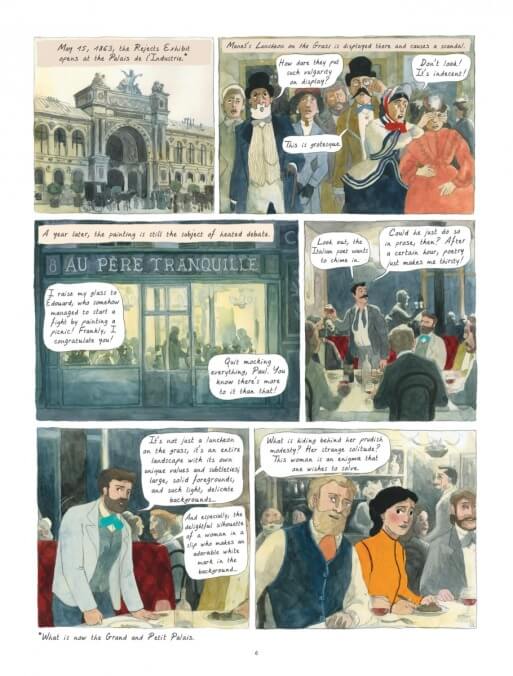

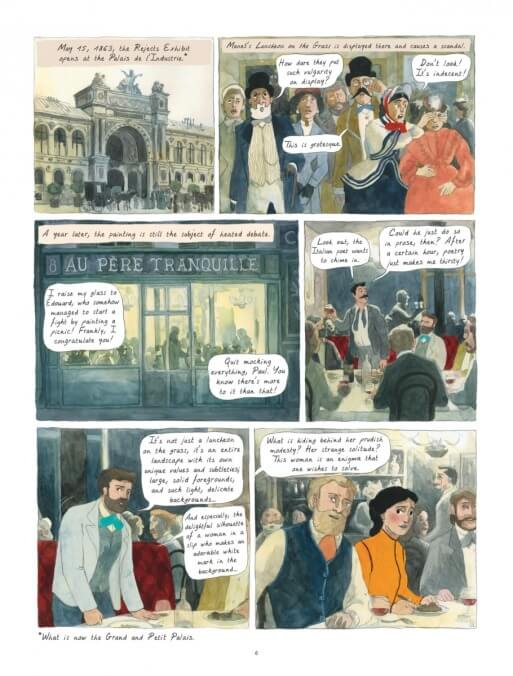

The heavily researched book traverses the Zolas’ lives from their first meeting, covering Emile’s rise to the top of French letters, his affair with Jeanne Rozerot and the children that union produced, Alexandrine’s confinement due to mental illness, her slow acceptance of Emile’s children, the Dreyfus affair (including the infamous “J’Accuse” letter), and the funeral of Emile. It opens with a page depicting the Zolas’ friend Édouard Manet painting his Le Déjeuner Sur L’Herbe with Alexandrine as the figure bathing in the background. This famous, controversial painting—and the subsequent defense of it that Emile raises in the following pages—is at the core of The Zolas.

Alice Chemama is devoted to recreating, with watercolors, the avant-garde artistic styles of the era on the page, particularly the impressionism of Manet, Claude Monet, and Paul Cézanne. One especially feels this with her colors; the soft recurring blue in particular seems taken directly from Manet’s work. A standout page reveals aspects of Alexandrine’s past by replicating the wordless novels of Frans Masereel and the many 20th-century comics artists inspired by his woodcuts.

It is in this dedication to replicating the artistic, linguistic, and historic style of the period where we encounter a recurring issue with The Zolas. Marcaggi’s writing shows clear evidence of deep historical research, like the inclusion of correspondence between Emile Zola and Paul Cézanne, and the well-documented world the book uses as its setting is expanded by footnotes. Often, this is done to give more information about a location, event, or a character depicted (but not named) in a panel. Without exception, this additional insight is not afforded to women. This isn’t necessarily a fault in Marcaggi’s writing: The archives from that era are composed of the writings of men, whether being about them or written by them. Accordingly, one would have to delve into the speculative to produce stories of women who are left voiceless in the archive—as is done, for example, by Saidiya Hartman in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments. The Zolas is strongest when it participates in this tactic, as in the aforementioned section that goes into Alexandrine’s backstory.

By not challenging the archive more forcefully, The Zolas, while breathtakingly written, translated, and rendered, feels lacking. The story is about the ways in which a creator is inspired by his muse but is also negatively affecting her life, yet it remains largely from one perspective. Alexandrine has a mental breakdown upon learning of Emile’s infidelity, unable to stop shouting; yet the narrative perspective focuses on how Emile has to keep her in a padded room to keep from hearing her screams.

The Zolas limits itself by depicting muses in a manner often done by creators. In one telling page showing the writing of the “J’Accuse” letter, Alexandrine says, “We are writing the most beautiful page of our lives.” However, the next panel features Zola, locked in his study room, writing throughout the night. Alexandrine inspires him, but he’s still depicted as creating in solitude.