There and back again: Searching for insight in Tolkien and the author’s Oxford stomping grounds

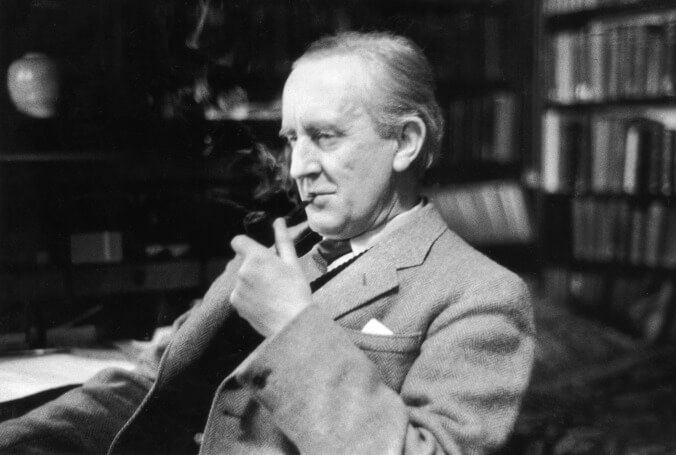

How do you translate the enduring popularity of Middle-earth to a film about the author who created it? That’s the question that plagues Tolkien, the new biopic of the life of J.R.R. Tolkien, writer of The Hobbit and The Lord Of The Rings. And it’s one I mulled after seeing the film and visiting Oxford on a 20th Century Fox-sponsored tour. The Hobbit forms one of my earliest memories of reading, and along with its follow-up, The Lord Of The Rings, began my love of fantasy. So I was eager to travel to England for Tolkien’s screening and junket, and especially a tour of Tolkien’s Oxford, thinking it would deepen my appreciation for an author who was monumentally important to the fantasy genre and to my own love of reading.

As cool as it was to trace Tolkien’s steps through the storied university, the trip wound up highlighting the folly of seeking to understand a person by visiting their old stomping grounds. There’s an undeniable allure to the type of tourism that marries fandom with an already renowned destination. As an American, I’m perhaps especially susceptible to the idea of a quintessentially British author in a quintessentially British place, and what is more British, to the foreign sightseer, than Oxford?

Inextricable with the idea of Oxford is its literary output, from Tolkien and C.S. Lewis to Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, perhaps my favorite book series of all time, which happens to revolve around an Oxford of a different universe—similar but quainter, in fact very close to how I envisioned Oxford as an excited tourist. I took pictures with my cellphone as our elderly tour guide showed us the places Tolkien spent time—the wall he scaled, drunk, to get to his rooms as an undergraduate; the pub where he met with his Inklings; the Oxford University press where he worked on some “W” words for the dictionary—but those places aren’t stand-ins for people who once populated them. They’re just places, only as important as we try to make them, no matter how hard we try to peer into the past through their windows.

Similarly, while Tolkien the film is pleasant in its own way, it acts better as a period piece detailing the early life of a creative soul who falls in love, enjoys the camaraderie of an artistic-minded group of friends, and goes to war. The problem with making a biopic out of an author’s life is that there’s nothing inherently interesting about watching that type of creativity unfold. The bigger problem is that tackling the life of this specific author—whose work is incredibly well-known, both through the books that have never been out of print and the films they inspired—risks making every moment depicted a direct correlation to what the audience is already familiar with. In other words, it risks fan service.

Tolkien opens on World War I’s western front in a scene that looks like The Return Of The King’s battle at the Black Gate set in the brimstone vista of Mount Doom. In short order, the film travels back in time to show a glowing ring reflected in a boy Tolkien’s eyes while his mother tells a story about a knight and a dragon that sounds uncannily like Cate Blanchett’s voice-over introduction in The Lord Of The Rings. From the Nazgûl-looking German calvary to a Gandalf-like philology professor, Tolkien makes the case that some of the most memorable images and ideas from the author’s work were pulled directly and literally from his life. This approach turns the biopic into a game of “spot the inspiration,” expecting fans to thrill when they hear Tolkien (played by Nicholas Hoult) softly utter the word “fellowship” when describing what his book will be about.

And perhaps for some fans of Tolkien’s work, there’s insight to be gained in seeing how pieces of his history—a strong group of friends, reciting Beowulf from memory at an early age—could be understood as influences. Personally, this fan found little pleasure in reducing the author’s life to the parts that can, speciously, be read in the work. While the film attempts to demonstrate how well-read and immersed in languages Tolkien was, it never figures out how to show the ways Tolkien drew on those those myriad stories, histories, and languages to create something totally new. Instead, Tolkien’s group of friends translates into his “fellowship” and the evils of war are Sauron.

This reductive reading was rejected by the medieval literature grad student who showed my group around Merton College, where Tolkien taught English courses, his background in philology and love of language heavily influencing the direction of the department. (It’s one of the only college English departments where “language” is listed before “literature.”)

In Merton’s garden is a famed stone table, where Tolkien and his friend C.S. Lewis supposedly wrote parts of their masterpieces together. The table is better known for what fans of Lewis’ work infer: that it’s the direct inspiration for Aslan’s table in The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe. But Tolkien devotees can also track visuals to this spot where they know Tolkien sat: From the table you can see two of Oxford’s famous spires—two towers, you see. “People say this is where Tolkien got inspiration for the two towers,” the grad student said as we sat at the table. “But my friend is a novelist and says that’s not really how it works.”

There’s something strangely belittling about attempting to whittle down the immensely creative feats of novel writing, especially an epic as deeply rich as The Lord Of The Rings, by drawing direct correlations between the work and what was in an author’s line of vision at a place where he’s known to have sat sometimes. It equates what a person sees and experiences in their life with the complex labor that is writing. Sure, experience can play a part, but they’re nothing without the long and absorbing process writers go through that involves reading and researching and sitting and thinking, contemplating ideas and evolving and shaping them into something that eventually, through more reading and researching and contemplation and writing, becomes a book.

That’s why Tolkien fails: It tries to show pieces of an author’s life that fed his creativity but ends up diminishing the feat of that creativity in the process. It’s hard to document writing in a visual medium, which is perhaps the reason the genre mostly stays away from authors in favor of musicians: There’s so much more in a musician’s life and output that the film medium can dramatize and depict. Writing, on the other hand, is an inherently solitary and quiet activity, the action taking place within the mind until it’s put on paper.

In Tolkien’s own words: “An author cannot of course remain wholly unaffected by his experience, but the ways in which a story-germ uses the soil of experience are extremely complex, and attempts to define the process are at best guesses from evidence that is inadequate and ambiguous.” In his forward to The Lord Of The Rings’ second edition, Tolkien addresses the attempts his readers had made to connect events in his life and the contemporary events in Europe to events in The Lord Of The Rings. He had clearly heard a lot of it, as he dedicates several paragraphs to refuting those readings.

To take one of the clearest examples: There’s a convincing argument to be made that Frodo experiences something very similar to post-traumatic stress disorder, and that Tolkien’s time in the battle of the Somme was on his mind when he wrote Frodo explaining why he wasn’t the same after returning to the Shire: “I have been too deeply hurt, Sam. I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me.” Yet Tolkien rejects this connection, writing in his foreword that the scouring of the Shire does not reflect a specific post-war England but a remembered England of Tolkien’s youth: “The country in which I lived in childhood was being shabbily destroyed before I was 10.”

What about World War II parallels? Published in 1954 and 1955, the three books that form The Lord Of The Rings seem to have been read by many as a direct response the most recent war, something Tolkien also flatly refutes in his forward:

As for any inner meaning or “message,” it has in the intention of the author none. It is neither allegorical nor topical. As the story grew it put down roots (into the past) and threw out unexpected branches […] The crucial chapter, “The Shadow Of The Past,” is one of the oldest parts of the tale. It was written long before the foreshadow of 1939 had yet become a threat of inevitable disaster, and from that point the story would have developed along essentially the same lines, if that disaster had been averted. Its sources are things long before in mind, or in some cases already written, and little or nothing in it was modified by the war that began in 1939 or its sequels. The real war does not resemble the legendary war in its process or its conclusion.

There are certainly obvious inspirations for Tolkien’s work: the overwhelmingly mythical nature of the whole story; timeless good versus evil and a moral philosophy among the characters; and the Finnish and Welsh languages, which Tolkien drew on heavily for his various Elvish languages (there are six total, two of them fully written). But trying to interpret a fantasy work through the lens of the author’s life and times points to the dangers of readers forcing the output of a writer into a narrow set of events and experiences, undermining the genius in favor of rote explanations.

If Tolkien is to believed about the scouring of the Shire (and I don’t know why we wouldn’t take his word for it), even one of the most “obvious” parallels between his life and his character’s is incorrectly inferred. The Tolkien biopic, and even a trip through Tolkien’s Oxford, run the risk of seeing information that isn’t there. You’ll learn more about who Tolkien was by reading his breezily charming Farmer Giles Of Ham and delving into the dense history-myth of The Silmarillion than you will watching a film forcefully and speciously make the connection between the battle of the Somme and Sauron. Not that readers can’t take what they will from Tolkien’s work: The author himself provides a better prism through which to analyze Middle-earth in the “applicability” of his stories to history.

I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history, true or feigned, with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse “applicability” with “allegory”; but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author.

What I read as pure allegory in the biopic wasn’t the intent of its director. Dome Karukoski sought to show a budding creativity in young Tolkien, how the experiences of his early life and making up a new language purely for the joy of it grew into the fantasy world we’re all familiar with. “There is not yet Morgoth, not yet Sauron, but there is this idea of evil,” Karukoski said of his approach to inserting fantastical elements into a fevered Tolkien’s battlefield visions. “You see the Nazgûl but it’s not the Nazgûl yet—I mean, I assume people will see it as a Nazgûl, but it’s actually not. He has a story from his mother, he sees this gallant white horse, forefather of Maedhros, ideal of a hero with a white horse. And slowly his mind corrupts during the war and that image turns into evil.” Karukoski said the same thing when I brought up Tolkien’s vision of Sauron in the battlefield: It’s not yet Sauron, but a vision of evil. Regardless of approach, a biopic of Tolkien’s life is always going to face this double-edged sword of a problem: The reason we’re interested in Tolkien the author is because we love his books, and those books left such a visual and semantic legacy that there’s no way to present the man without bringing along the inherent baggage of The Lord Of The Rings.

Karukoski’s enthusiasm for what might be called the extended Tolkien universe was my biggest takeaway from my interview with him, and the added context makes clear that the many allusions inserted into Tolkien’s early life suggesting inspiration for later writing springs from a deep well of love the director has for the author’s work, an attempt to show “the ways in which a story-germ uses the soil of experience.” Reviewing our conversation, I realize that we spent almost no time discussing Tolkien himself. Instead, we gravitated to which stories mean the most to us, how we connected to them when we were both young and lonely, and which ones we would be most excited to see adapted in the future.

I hope Karukoski does get a chance to really engage with Tolkien’s work in some future project, because I think it would be much more interesting to see his take on, say, “Túrin Turambar,” which Karukoski cited as his favorite story from The Silmarillion. (He also pointed out, correctly, that the downfall of Númenor is basically a ready-made season of television.) Tolkien’s actual life story is not all that interesting, but his legacy is mythic; the myth overshadows the man, and the success of his work contributes to the failure of the biopic. And Karukoski’s attempts to show the nascent creativity forming—the vision of pure evil, meant to be abstract but bound to be interpreted literally by anyone familiar with the film adaptations or Tolkien’s illustrations—are the most interesting parts of the biopic, precisely because they’re the most wildly out of tone for this kind of movie. So here’s hoping the Tolkien biopic reengages (or, perhaps for a younger demographic, just introduces) people with Tolkien’s work, and that people like Karukoski, who see the potential to turn odd myth stories that aren’t obvious choices for screen adaptations, get the chance to do so.

The Tolkien biopic and a tour of Tolkien’s Oxford were ultimately futile attempts to connect with the author. Maybe it’s just that extratextual knowledge rarely adds much meaning to the text itself. There’s nothing like delving back into a beloved book, because there’s no replacement for the fantasy world that exists between your imagination and the author’s. Or, as Thorin Oakenshield tells his band of dwarves and Bilbo, “There is nothing like looking, if you want to find something. You certainly usually find something, if you look, but it is not always quite the something you were after.”