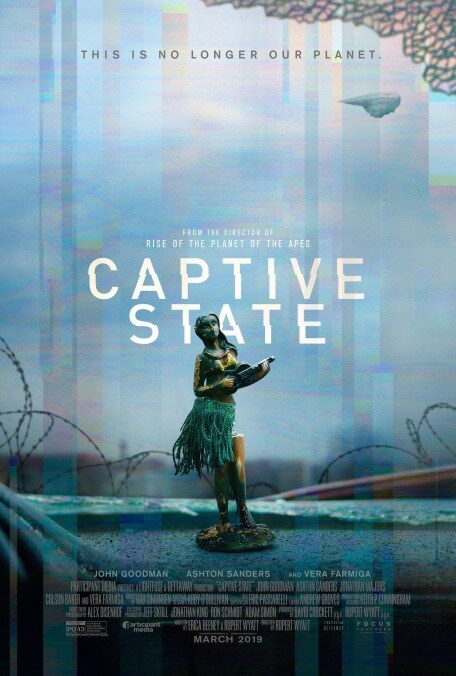

There are few signs of life in the curiously dour alien-occupation drama Captive State

It’s really rather impressive, the extent to which Captive State sucks everything even potentially fun out of the alien-invasion genre. That includes, for the most part, the aliens themselves, who are spoken of much more often than they’re seen, words being free and all. Set in the aftermath of a worldwide extraterrestrial takeover, this economically scaled science-fiction drama makes a real attempt to imagine what such an occupation might look like, and how the resistance to it might operate. One can admire, perversely or otherwise, how utterly straight the film plays that scenario, and perhaps appreciate how it resists devolving into an Independence Day-style fire- or dogfight, regardless if the lack of spectacle is more of a cost-saving measure than anything else. But it’s not unreasonable to expect something like excitement out of a story about freedom fighters plotting to take back the planet. Captive State does not clear that fairly low bar.

It takes place in 2025, nine years after the world’s leaders collectively surrendered to an army of technologically superior colonizers from above. (It’s a real “I, for one, welcome our new insect overlords” situation for the greedy politicians and other collaborators.) The aliens have made Chicago their home base, tunneling under a walled-off stretch of downtown real estate and plopping a jamming device on the peak of Sears Tower, or Willis Tower, or whatever the space invaders have opted to rename it. “Legislators,” as the more civic-minded ETs are pointedly called, make the laws. “Hunters” enforce them, sticking tracking devices in necks. To the less willingly subjugated, they’re all just “roaches.”

Caught between the cooperative and the resistant is Gabriel (Moonlight’s Ashton Sanders), whose parents died during the invasion. Only rumored to be dead is his older brother, Rafe (Jonathan Majors), celebrated as a folk hero for his role in a failed uprising called Wicker Park, after the part of town where it went down. (The planned new insurgency is nicknamed Pilsen; by the end of the film, Chicagoans will feel like they’ve spent a day with a friend who can’t stop namedropping the only two neighborhoods he knows.) Neither brother is a barrel of laughs. Actually, no one in this movie ever cracks a smile or tells a joke or exhibits much in the way of a personality. Which is a shame, because the cast includes a lot of talented actors (Vera Farmiga, Alan Ruck, James Ransone) and also Machine Gun Kelly. The only one handed anything like an actual role is John Goodman, cast as a veteran cop who’s risen to the position of the aliens’ most trusted human Gestapo. But Goodman downplays the faint flickers of conscience so thoroughly that this Lives Of Others subplot barely registers.

Returning to interspecies conflict almost a decade after he rebooted the Planet Of The Apes franchise, director Rupert Wyatt works in a boots-on-the-ground handheld style that might best be described as discount Kathryn Bigelow. His script, coauthored with Erica Beeney, lurches to life when zeroing in on the moving parts of the resistance, like the way a phone call becomes a classified ad becomes a secret message. Is it at least a little bold, asking audiences to side with radicals trying to topple an oppressive American government? Yet a more imaginative film might have envisioned how society would actually be transformed by the presence of alien forces. In its high concept, Captive State sees only a barely disguised metaphor for life in a police and surveillance state. It’s convenient, certainly, that the aliens represent a faceless, all-purpose authoritarianism, as that mostly justifies keeping them frugally off screen. When we do see the creatures, spindly and spiny and none too convincing, they’re under cover of darkness, the oldest trick in the F/X-obscuring book.

In principle, this is the kind of sci-fi movie you’re supposed to root for. It’s relatively short and quiet, not overblown and noisy. It tells an original story, instead of adapting some piece of highly coveted IP. And out of necessity or not, it downplays effects in favor of character conflict and ideas. Yet so determined is Captive State to ground itself in contemporary anxieties, to be taken seriously as a grimly poker-faced allegory, that it makes all the alien stuff feel almost arbitrary, like window dressing or an afterthought. Wyatt fails even to offer any memorable images. Well, maybe there’s one: a shot of a dog staring skyward as three brilliantly blazing UFOs rocket overhead. Like us, perhaps, he’s searching for something, anything, exciting to look at in this ashen urban landscape.