Arnaud Desplechin loves a good detour. Since making his international breakthrough in the mid-’90s, the French writer-director has built a career of messy, novelistic ensemble mosaics like A Christmas Tale and Kings & Queen that don’t so much move from A to B as zigzag wildly across the entire alphabet, taking special delight in discursively swerving off course, into backstory and expository side business. That’s especially and perhaps detrimentally true of Ismael’s Ghosts, Desplechin’s most diversion-prone picture yet. Even coming from a filmmaker who walks a narrative line like a drunk driver tipsily failing to prove his sobriety, this is scattershot stuff—and maybe too much movie for one movie. Yet it’s been made with enough brio and confidence to drag a chaos-tolerant viewer along for the ride. You want to relent to its winding navigation as fully as the director himself has surrendered the wheel to his muse.

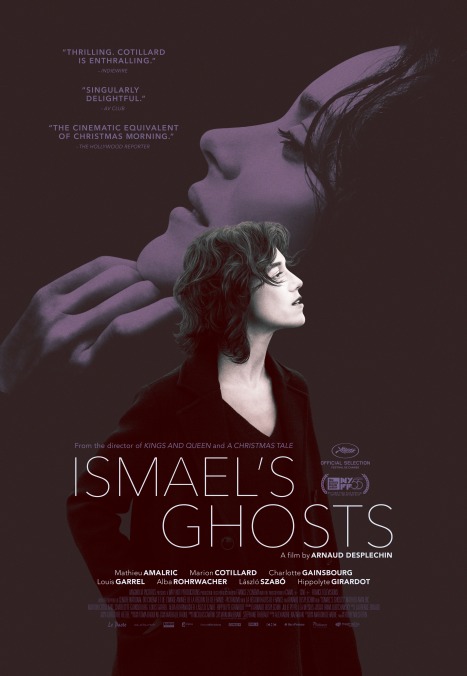

And who’s better equipped, really, to steer an out-of-control Desplechin vessel than his longtime leading man of choice, Mathieu Amalric? The eccentric French actor has been anchoring the filmmaker’s work since 1996’s coming-of-age epic My Sex Life… Or How I Got Into An Argument, and his testy, manic energy makes him a perfect surrogate for the man behind the camera. Amalric plays Ismaël Vuillard, a notoriously difficult filmmaker still mourning the ex-wife, Carlotta, who disappeared 20 years earlier without a trace, leaving her husband and her elderly ailing father, fellow filmmaker Henri (László Szabó), to presume her long dead. “Don’t be jealous of a ghost,” Ismaël tells his new lover, Sylvia (Charlotte Gainsbourg), with whom he’s finally settled down. But then from out of the woodwork she emerges: the long-lost Carlotta (Marion Cotillard), re-materializing in the blinding daylight as suddenly as she disappeared, ready to rekindle what she abandoned two decades prior.

It’s not such a bad problem to have, choosing between Charlotte Gainsbourg and Marion Cotillard. But Ismael’s Ghosts sees in this fantasy love triangle a tug-of-war between past and present. Who is Carlotta, after all, but a specter of old glories and trauma, gusting back in to complicate Ismaël’s romantic contentment, to confront him with unfinished business? It’s a theme that haunts much of Desplechin’s work, with its constant chronological leaps, always tying characters to the histories they can’t escape. His last film, My Golden Days, also featuring Amalric, was a return to the past in more ways than one, spinning a belated prequel to My Sex Life. A similar (if looser) relationship animates Ismael’s Ghosts, which hands Amalric’s neurotic filmmaker the same name his neurotic musician sported in Kings & Queen—a connection fortified through an offhand reference to that earlier triumph’s familial entanglements. Desplechin links not just then and now, but also life and career, which are as entwined for Ismaël as they presumably are for his creator.

So dramatically and metaphorically potent is the central premise that it’s hard not to be irked by the way Ismael’s Ghosts careens off in several divergent directions. That was true of the version that opened last year’s Cannes Film Festival, and it remains true of the “director’s cut” opening now in American theaters. Desplechin has bulked up the connective tissue between his various subplots with 20 extra minutes of running time, and he’s also productively readjusted the film’s flow, making at least some structural sense of its left turns. But this is still a stubbornly digressive film. It begins the same way, with a mislead: the introduction of hotshot, much-ballyhooed diplomat Ivan (Louis Garrel), who turns out to be a heavily fictionalized version of Ismaël’s real brother, and the main character in a spy thriller that keeps intruding upon the main story. It’s not the only distraction: Desplechin gradually drifts away from the two very different women competing for Ismaël’s affection, his focus shifting to the protagonist’s tortured writing process. In the way of almost all movies about artistic block, the fictional creative struggle reflects, and perhaps attempts to excuse, the real one behind it. When Ismaël transforms his workshop into a spider’s nest of story notes connected with yarn, we’re almost surely seeing Desplechin’s winking acknowledgment that he couldn’t make this mess of plot strands cohere. But in reality, Ismael’s Ghosts doesn’t so much lose the thread as set it ablaze like a fuse.

This is, in other words, a self-indulgent work on multiple levels, from its shaggy plotting to its focus on the “difficulties” of being a revered artist to the, again, less-than-sympathetic dilemma of being caught between two beautiful, adoring lovers. But then, doesn’t one look to this maestro of excess for a little self-indulgence? Certainly, the deluge of flashbacks and anecdotal asides are part of what make Desplechin’s movies, at their cluttered best, so singularly delightful. Here, the director toggles around with impish enthusiasm, staging moments—like Cotillard’s loose-limbed dance to Bob Dylan’s “It Ain’t Me Babe” or a brief detour aboard a speeding passenger train—for nothing but the sheer pleasure of them. He also trots out the usual stylistic tricks that have always given even his lesser efforts an infectious energy: the fades and superimpositions, the dramatic zooms and irises, the churning orchestral accompaniment. Maybe too much movie isn’t such a bad problem to have either.