There may have been another, older New England

This week’s entry: New England (medieval)

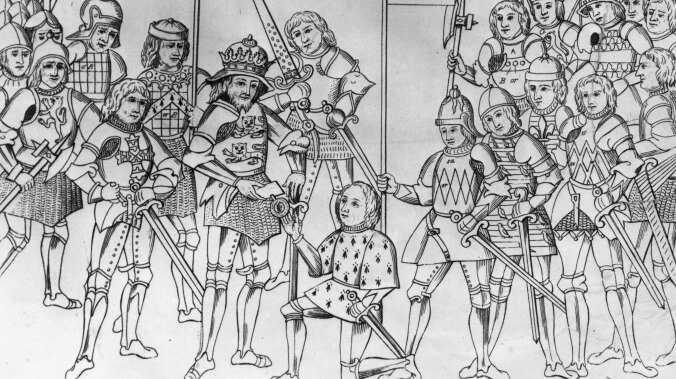

What it’s about: The other, older New England! When William The Conqueror, well, conquered Merry Olde England in the 11th century, some refugees fled to nearby Scotland or Ireland, and some fled all the way to Constantinople. The Byzantine Empire eventually granted them territory near the Black Sea which they named New England… or did they?

Biggest controversy: Like the quiet, mild-mannered Bostonian, the medieval New England might not actually exist. Chronicon Universale Anonymi Laudunensis, a history of the world through 1219 written by an anonymous English monk in France, recounts the tale, but the only other collaborating text is a mention in the 14th-century Icelandic Játvardar Saga, a biography of English king Edward The Confessor, and it probably used Anonymi as its source. Historians do largely agree that there were English immigrants in Constantinople in the late 1000s, but there’s no actual evidence that New England existed, just speculation.

Strangest fact: That speculation is supported by some place names on the north coast of the Black Sea. The Ottoman fortress Sujuk-Qale (now Russian port city Novorossiysk) may have taken its name from the word “Saxon,” and there was a medieval city of Londina not far away.

Thing we were happiest to learn: If there was a medieval New England, the New Englanders earned their place there. According to Játvardar Saga, the English refugees were in fact “a great host” of 350 ships led by the Earl Of Gloucester. They sailed for the Byzantine Empire, which was currently being invaded by Muslims. Gloucester’s forces captured Ceuta (just across the Strait Of Gibraltar from Spain and still a Spanish possession to this day), and the Mediterranean islands of Majorca and Menorca. When they reached Constantinople, the city was under siege, but the English fleet was able to drive off the attackers. Alexius I Comnenus, who ruled Constantinople, asked the English to remain in Constantinople as his bodyguards, but some of the English wanted their own land. (The English refugees becoming Alexius’ guard seems to be accepted historical fact; it’s the land grant that’s still a matter of speculation.)

Thing we were unhappiest to learn: Muddying the waters is another version of events that tries to have it both ways. Benedictine monk Orderic Vitalis’ 12th-century Ecclesiastical History details the Norman conquest and mentions exiles fleeing to the Byzantines. In his version, the Greeks and the English fought the Normans side-by-side, Alexius laid the foundations of a town called Civitot to resettle the English “some distance from Byzantium,” but then brought them back to the city to be his guards. However, historians have called this version of events “impossible to verify,” and in one case, “fantastic.”

Also noteworthy: There’s also a possible version of events in which the New Englanders became pirates. As Chronicon Universale tells it (though no mention of this is made in the Icelandic saga), when Alexius I sent an official to collect tribute, the New Englanders killed him. Fearing retribution, the New Englanders still in Constantinople fled the city, taking up piracy. No word as to what happened to the people actually living in New England, but we might have a clue as to why that New England no longer exists.

Best link to elsewhere on Wikipedia: The English-influenced place names mentioned earlier were found on portolans, Mediterranean nautical charts first found in the 13th century, praised in later eras for their remarkable accuracy. The techniques used to make them were lost to history, but they were produced in Italy, Spain, and Portugal, though it’s not clear which region the maps originated from.

Further down the Wormhole: Given how much of the world the British colonized, there’s a considerable British diaspora, included in the New England page. Naturally there are a significant number of English Americans, given our origins as a British colony. In fact, under “Notable People,” Wikipedia mentions only the handful of U.S. Presidents who don’t have English ancestry, and most of those are Scottish and/or Irish, apart from Martin Van Buren, the child of Dutch immigrants on both sides who was the first president to be born in the United States and not the pre-revolutionary colonies.

While Van Buren was born in New York, died in New York, and served as New York’s state senator, attorney general, U.S. senator, and governor, his presidential papers are for some reason housed in Tennessee, at Cumberland University. Cumberland’s football team was a powerhouse in the early days of the sport, peaking with a 1903 season in which they went 4-1, allowing only 6 points all season (in their one loss), and then tied in their game with Clemson in the postseason. But their fortunes had declined by 1916, when they suffered the most dramatic loss in the history of football. We’ll celebrate Super Bowl Sunday next week by recounting the 1916 Cumberland vs. Georgia Tech football game, and hoping Kansas City hands an even more dramatic loss to Tom Brady.