There’s a touch of Nathan For You absurdity to the droll sports documentary Infinite Football

The ostensible subject of Corneliu Porumboiu’s Infinite Football is the Romanian writer-director’s childhood friend, Laurentiu Ginghină—by day a middle-aged, paper-pushing bureaucrat, but in his off time, a self-described revolutionary of football. When the film opens, Ginghină tells of how, in 1986, he fractured his fibula while playing a game of soccer, an incident that would trigger a lifelong obsession with the sport. His epiphany? That the injury was neither his nor the other players’ fault. “It was the fault of the imposed norms,” he says. The rules of the game needed to change, and he would be the one to rewrite them.

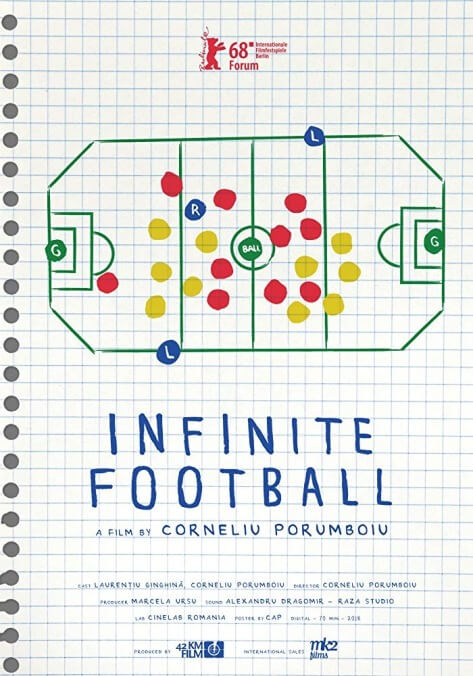

With the wide-eyed look and worn demeanor of a conspiracy theorist, Ginghină makes for a curiously compelling presence—oblivious and vacant-seeming, but also obsessive and precise in his efforts to perfect the vaunted sport. His first two proposals: Get rid of right-angled corners by employing an octagonal field of play (closer in shape to a hockey rink); and divide the players into sub-teams, with each sub-team limited to playing in a demarcated portion of the field. The motivation? To “increase the ball’s speed by decreasing the players’ speed.” Such outlandish ideas and made-up rules arrive at a steady rate over Infinite Football’s brisk runtime, with the director’s affable onscreen presence often balancing the football enthusiast’s bewildering eccentricity. While the film is billed as documentary, and is straightforwardly filmed as such, it often has the feel of a mock-doc, or perhaps a stray Nathan For You episode ported over to Romania. It’s never really clear whether Ginghină is entirely sincere (and thus to some degree delusional) or just playing for the camera. If it’s the latter, he impressively never once breaks character.

All this is in keeping with Porumboiu’s visually unadorned style and precise (others might say “narrow”) comic sensibility, which often risks boredom by intentional repetitiveness, but pays off for those attuned to his droll wavelength. A major figure of the Romanian New Wave, he first made his mark with the cheekily titled Police, Adjective and has continued to serve up curios like When Evening Falls On Bucharest Or Metabolism, sharpening his absurdist humor to a gleaming point all the while. His last film, The Treasure, which doubled as a deadpan survey of present-day Romanian bureaucracy and a literal excavation of the nation’s Communist past, managed a canny structural sleight of hand, expanding in political scope even as it (literally) burrowed into its characters’ banal obsessions.

Something of the same effect occurs here. There’s a gradual pileup of ostensibly digressive details: Ginghină’s failed plan to move to an orange farm in the United States (“a country of freedom”); a visit from an elderly woman who, even 27 years after the revolution, has yet to receive restitution for her land; a wedding photographer’s admission that he’s interested in capturing “the phenomenon, not the person.” Eventually, Ginghină’s interest in rewriting the rules of soccer takes on larger socio-political questions of the collective versus the individual, state bureaucracy, and issues of governance. It’s no coincidence, after all, that Porumboiu chose to begin the film with Ginghină’s injury in 1986, just three years before Ceaușescu’s fall. The question Porumboiu poses (and which he makes literal at one point) is a familiar, but essential one: When freedom is concerned, where is one to draw the line?

This is rich material, sharply developed. It’s also touchingly optimistic about man’s capacity for incremental change. Porumboiu’s camera is unobtrusive, and his overall approach miniaturist, as exemplified by the film’s closing shot: a slow track along a deserted road at daybreak, accompanied by a series of summative political and philosophical ruminations. But such virtues don’t obviate the fact that the film can be rather dull, since its interest is almost exclusively structural, with compensating pleasures like droll humor or wry characterization in uncharacteristically short supply. Because the Romanian director’s self-imposed cinematic constraints are also so stringent, it’s ultimately impossible for the film to fail conspicuously. But much like his friend and subject, Porumboiu fails to fully convince us that his rules are worth playing by.