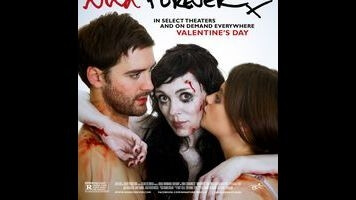

There’s bloody pathos in the resurrected-lover horror of Nina Forever

Who among us hasn’t been haunted by the specter of a former relationship we just can’t seem to shake? Rendering gruesomely literal the all-too-common fear that your new significant other can’t let go of their previous beau, Nina Forever seizes on that conceit and turns it into a from-beyond-the-grave nightmare. (And in the process disproves a theorem known as the Over Her Dead Body injunction: That this high-concept premise can only result in a limp noodle of a comedy, a rule recently and sadly upheld by Joe Dante’s underwhelming Burying The Ex.) Also, it transmutes the nightmare to flesh and blood, turning this particular ghost of a girlfriend past into a dripping, creaking, reanimated corpse. If you’re having girl problems I feel bad for you, son, but thank your lucky stars those 99 problems don’t include “being stalked necrotically.”

The film follows the budding romance between Holly (Abigail Hardingham) and Rob (Cian Barry), a pair of young Brits who meet-cute in the stockroom of their workplace grocery store. He’s depressed over the auto-accident death of his girlfriend Nina (Fiona O’Shaughnessy), but Holly, determined to demonstrate that she’s darker and weirder than anyone credits, finds his possibly suicidal urges alluring. “I’d love it if my boyfriend tried to kill himself ’cause I died,” she says, demonstrating that the quirk is strong with this one. Happily, it’s Holly’s movie more than Rob’s, because otherwise such an inexplicable and out-of-nowhere attachment to a mopey stock-boy would approach Manic Pixie Dream Girl territory. Instead, Holly’s desire gets top billing, and the two connect fast, with their first date winding up back at Rob’s place for some intense lovemaking. But as they writhe, the white sheets of Rob’s bed begin to pool with blood, hands crawl their way from underneath, and soon the still-dead-but-very-much-corporeal Nina croaks into existence, demanding to know what Holly’s doing with her boyfriend.

From here, the film begins its journey into the emotional head space of two people who want to be together, but find themselves forced to deal with a trauma from the past, one that isn’t so easy to heal. After her initial revulsion at the problem—sex with Rob always triggers a viscera-laden visit—Holly decides to embrace the situation and make the best of it. But Nina proves stubbornly resistant to any compromises or peace treaties. After inviting Nina to be a willing participant in their lives fails, Holly and Rob try to find the right way to “honor” her, in hopes they’ll happen upon the proper ritual or offering that’ll let this implacable corpse rest. But again, Nina refuses any and all approaches. “I don’t want that,” she mutters simply, when they try to reason with her, as though she were still alive. “I don’t want.” Eventually, they reach their breaking point, and Holly and Rob commit to eradicating any and all traces of his ex from their lives, committing to an “out of sight, out of mind” strategy to banish this blood-soaked spirit for good.

Anyone who’s ever tried to get over a painful end to a relationship can probably guess how well this plan works, but the beauty of Nina Forever is how it upends expectations, avoiding any generic resolutions and refusing to fall into stereotypes of male and female behavior. Whether it’s Rob’s awkward friendship with Nina’s grieving parents, or Holly’s alternately welcoming and threatening approaches to Nina, the movie doesn’t cheat on its emotional stakes. Physical ones, either—the visceral presence of Nina is conveyed through an abundance of blood, with O’Shaughnessy giving a performance both repulsive and hypnotic, an undead woman who retains the memories and personality of her former self, but sapped of any will or desire. Her appearances are genuinely haunting, with directors Ben and Chris Blaine (in their feature-film debut) cross-cutting among various perspectives in a unsettling manner, creating a mood of unease that simultaneously attracts and distances, rather like Nina herself. It’s unnerving even as it’s bleakly comical, in the best way.

At least, it is when the brothers Blaine want it to be. For all their skill in playing this situation straight and achieving a darkly disquieting vitality (the sound mixing is especially good, with faint music cues pulsing under sickly hums, cracks, and pops akin to a David Lynch production), the movie hedges its bets with more overt comedy. After several of Nina’s mordant appearances, the film shifts gears into light-hearted relationship or comedic montages, set to an upbeat indie score, sections of the film that wouldn’t feel out of place in a standard-issue Sundance-assembled dramedy. Given the movie’s success in mining the Nina situation for black comedy amid the fraught drama, these interludes are a little tonally distracting—an attempt at more daring genre-blending that comes across instead like playing it safe. Nina Forever works best when it doesn’t shy away from the emotional instability of its messy love triangle, letting the various feelings and desires splay out in all directions simultaneously.

But despite these uneven moments, the film still serves as a dark and morbid fable about the poor choices people can make in their efforts to prove that they are how they see themselves. (The film’s tagline is “a fucked-up fairy tale,” which does a bit of a disservice to the depths the actors bring to their underwritten roles—Hardingham, in particular, is magnetic, like a millennial Ruth Wilson.) The complex relationship stuff happens mostly off screen, with the emphasis squarely on the moments when this new couple must confront the specter of Rob’s dead love. And by the end, the film suggests that the inability to move on doesn’t always stem from where we think; some people, Nina Forever says, go looking for drama—and if you’ve made a blood-soaked bed, you might have to lie in it, long after you’re ready to leave.