There’s more to Gilda than just an iconic hair flip by Rita Hayworth

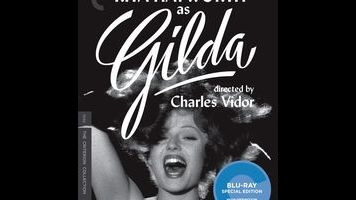

More than perhaps any other film in history, Gilda is best known for a single quick shot: the first appearance of the title character, played by Rita Hayworth (in her most famous performance). Even if you’ve never seen the movie—which was originally released in 1946, and now joins the Criterion collection—you’ve probably seen this moment, which turns up in virtually every montage devoted to classic Hollywood. The Shawshank Redemption (which was adapted from a Stephen King novella titled Rita Hayworth And Shawshank Redemption) even makes it the centerpiece of one scene. “Here she comes,” Red tells Andy, right before it happens. “This is the part I really like, it’s when she does that shit with her hair.” And the entire prison audience subsequently goes wild when Hayworth-as-Gilda pops into the frame from below, with a head snap that sends her tresses flying backward and then tumbling forward. With the possible exception of Orson Welles in The Third Man, it’s the most memorable introduction to a character of all time, and so iconic that one can easily overlook the instant at the end—which usually gets cut off during clips (as it does in Shawshank)—when Gilda’s eyes shift focus ever so slightly, registering someone unexpected, and her radiant smile is abruptly replaced by a look of alarm.

Just as that shot is about more than its va-va-voom impact on cinema history, so Gilda itself is much more than a single indelible image. No film noir course would be complete without it, in part because it’s at once prototypical and highly unusual. The story is basic: While skulking around Buenos Aires, crooked gambler and all-around heel Johnny Farrell (Glenn Ford) meets a wealthy casino owner, Ballin Mundson (George Macready), who admires Johnny’s impetuousness and hires him as his right-hand man and muscle. When Ballin returns from a trip with a new wife named Gilda, however, it quickly becomes clear that she and Johnny are already well acquainted. Ballin, no dummy, intuits this as well, but trusts both of them to behave. When Gilda starts shacking up with everyone in Argentina but Johnny, openly flaunting her infidelity, Johnny takes steps to shield his boss from the truth, even volunteering to escort Gilda—with whom he’s plainly still obsessed—to and from her liaisons. It’s only a matter of time before Ballin finds out, though what happens when he does sends the film in an unexpected and even more sordid direction.

Part of Gilda‘s fascination is the way that it complicates the idea of the femme fatale. (Bear in mind that terms like femme fatale and film noir were coined decades later; nobody at the time was conscious that they were creating a genre.) Hayworth plays Gilda with a layer of bravado that masks deep insecurity; the character as written is something of a monster, but it’s strongly implied that Johnny’s behavior in their prior relationship is largely responsible for her twisted psyche. Ford, for his part, doesn’t shy away from making Johnny flat-out repugnant, especially when he manages to turn the tables on Gilda in the film’s third act. Indeed, all three of the main characters are fairly despicable. If one’s sympathy gravitates toward Ballin, it’s because he at least demonstrates some self-awareness. When Gilda assures him that she hates Johnny now, Ballin thoughtfully replies, “Hate can be a very exciting emotion. Very exciting. Haven’t you noticed that? There’s a heat in it that one can feel. Didn’t you feel it tonight? I did. It warmed me. Hate is the only thing that has ever warmed me.” Gilda’s director, Charles Vidor, isn’t generally considered much of a stylist, but the way he shoots this creepy exchange, which begins as a close-up of Gilda on the left side of the frame and then shifts to place her horizontally on the right side, with Ballin out of focus in the foreground as he speaks, is extraordinary in the way that it visually mirrors the viewer’s shifting loyalty.

Given the degree of noxiousness and perversity on display, it’s genuinely bizarre that Gilda ultimately turns out to be the rare film noir with a happy ending. In no way does this sudden spasm of righteousness feel earned or appropriate; only the ending of L.A. Confidential rivals it for seeming wildly out of place, to the point where it threatens to retroactively ruin the entire movie. In part, it comes across like a desperate effort to disguise the unmistakable homoerotic subtext of Johnny and Ballin’s relationship, since the former’s devotion to the latter feels more tender and romantic than does anything involving either of the two men and Gilda. (Gilda’s sexuality, while blatant, is generally directed toward the audience, most notably in the famous “Put The Blame On Mame” number that she performs while wearing a gravity-defying strapless black satin dress that has its own Wikipedia page.) While the forced optimism prevents Gilda from having the same gut-wrenching impact as, say, Double Indemnity or The Postman Always Rings Twice, however, it also inadvertently serves as a reminder that things aren’t always as cut-and-dried as they appear. Gilda’s unforgettable entrance is more complex than most people remember, and so, too, despite its lapse in courage at the final buzzer, is this remarkable movie.