There’s nothing spooky and a lot irritating about the showbiz-family affair Clara’s Ghost

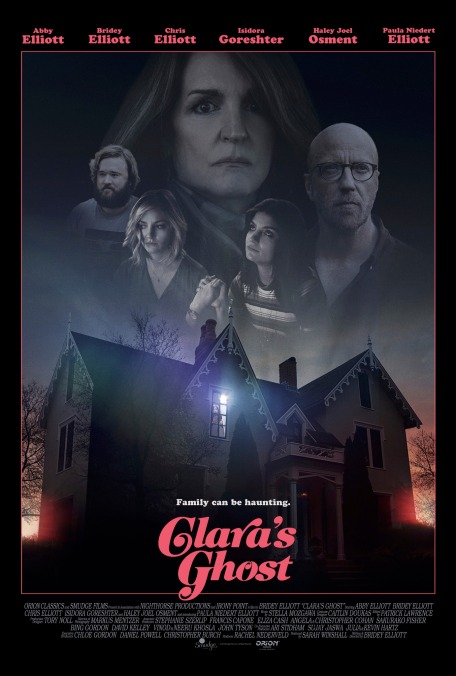

Art imitates life a bit too strenuously in Clara’s Ghost, the first feature written and directed by Bridey Elliott. (She’s probably best known for her starring role in the indie comedy Fort Tilden.) Set almost entirely in a rich Connecticut family’s home, this clumsy quasi-supernatural psychodrama features the entire immediate Elliott family. Bridey and her sister, Saturday Night Live alumna Abby Elliott, play sisters Riley and Julie Reynolds, who are likewise both actors. Their father, Ted Reynolds—also a famous actor—is played by their real-life father, Chris Elliott. And though their real-life mother, Paula Niedert Elliott, has never previously appeared onscreen, Bridey has chosen not only to cast her as matriarch Clara Reynolds but to build the entire movie around Clara’s feeling of being left out, which one can’t help but imagine Paula might share. Unfortunately, like most home movies, it’s of precious little interest to non-relatives.

Certainly, anyone who sees Clara’s Ghost anticipating spookiness will be sorely disappointed. Clara does repeatedly glimpse the ghostly figure of a woman (Isidora Goreshter), who’s apparently one of the 19th-century house’s former occupants. But it quickly becomes clear that this specter, which shows up at windows demanding to be let inside, is fundamentally metaphorical, embodying Clara’s anxieties and isolation. The rest of the family is oblivious, too caught up in their own self-centered carping to notice. Julie has a looming marriage she’s afraid will be a disaster; Riley wants Julie to take part in some nostalgic project related to their childhood fame as the “Sweet Sisters”; Ted’s career is on the wane, and he’s just lost a role in a particularly humiliating way. No wonder Riley calls her local weed guy, Joe (Haley Joel Osment), who shows up with the goods and then sticks around to referee all the combative banter.

To her credit, Bridey isn’t afraid to make her family’s alter egos repellent, what with Julie wondering if she should send her bridesmaids goal weights and Ted insulting an audition monologue that he’d insisted one of his daughters perform. But sustained insufferability needs to be either funny or incisive, and the Reynolds family is neither. Ted, Riley, and Julie constantly pepper their dialogue with movie references, which makes sense but is lazily executed; there’s no indication that Clara finds these quotations suffocating, and many of them, like Ted’s out-of-nowhere recitation of Robert Shaw’s celebrated monologue from Jaws, play like filler. (There are also two sequences in which characters sing along at length to decades-old pop songs: Clara does “Georgy Girl” solo in the kitchen, and later everyone but Clara portentously acts out “MacArthur Park.”) At one point, Joe praises a stand-up comic named Matt Byrne and attempts to replicate one of his routines. The scene is one long flatline, and when Byrne turns up in the end credits as one of the film’s key Kickstarter backers, it’s hard not to feel ripped off.

None of this might have mattered as much had Paula succeeded in making Clara’s pain deeply felt. From the opening scene, in which Clara somehow loses a shoe while driving (or believes she has, anyway) and attempts to file a police report about it, Paula’s performance is aggressively mannered, which is entirely the wrong approach; the role really required a professional actor, ironic though that would admittedly be. And the ghost, even functioning as a blatant metaphor, is conceptually underdeveloped to the point of almost being irrelevant—just a misleading marketing hook. Bridey ends the movie with what playwright Christopher Durang once called a “dot dot dot” ending, suggesting that Clara’s haunting will persist even though order has ostensibly been restored. That prospect isn’t so much horrifying as it is exhausting.