Fair enough, Dennis. Let’s look at the “suicidal guy on the bar’s roof” episode “Paddy’s Has A Jumper” purely from the emotionless, feelings-free, Netflix-style algorithmic perspective that, at episode’s start, has sent the Gang down an unlikely binge-watching rabbit-hole involving the suspiciously British period streaming drama Gainsborough Gardens. Taking our cue from Dennis’ approximation of the bloodless perfection of pure science and math in determining human behavior, likes, dislikes, and life and death, our appreciation of this episode of television (written here by Dannah Phirman & Danielle Schneider) should follow in lockstep progression according to how closely it adheres to the blueprint. So . . . let’s go to the data.

Now, there’s at least a few complicating factors that lend an air of urgency even to Dennis’ superior logic. For one thing, Frank can’t get back in with their fish and chips. For another, as the Gang spitballs, they ruminate on the pros and cons of being known as “the suicide bar” (as opposed to Paddy’s current reputation as, one can only guess, “the bar where no one ever seems to be working,” or “the bar that occasionally and wantonly serves the underaged”), with the eventual lure of lucrative infamy winning out. (Suggested theme drinks: The Last Call; The Lemon Drop; The Jump Shot; Mac’s game-winning Cosmo-fall-itan. Suggested jukebox songs: “Free Fallin’;” “Highway To Hell.”) Plus, Charlie’s all in on Dee’s idea of a nightly haunted house, undoubtedly peopled by the spirits of the drunk and damned.

Complication and grossness: Frank. Isolated on his fish mission, Frank finds himself stuck behind police tape, happily munching from his grease-slicked paper bag of the Gang’s food. Frank is often odd Gang member out, his age and own particularly atavistic brand of awfulness sending him scurrying on a parallel, if somehow more ridiculously grubby journey to the rest. Here, his panic over the Gang using the unnervingly prized and hole-bored casaba melon he keeps in the bar safe, sees him trying to bull his way past the police cordon in order to save what the rest of the Gang assumes is his own personal, low-cost sexual aid in order to test Dennis’ first flowchart step of whether a human head would smash open. (Charlie’s original egg test fails since he forgot he’d hard-boiled it, and it’s some unidentified creature egg he found in a burrow.)

I love Danny DeVito, and love him on Sunny, but sometimes Frank’s shenanigans can feel extraneous, too broad, or both. Or, as here, shoehorned in by some clunky writing. It took a few views to realize that Frank never means to suggest to the obliging officer that he’s the father of the poor sap on the roof, but is, instead, just babbling about his actual (sort-of) son Dennis “doing something stupid” like, for example, dropping his prized sex-melon on the floor. The return of Philly reporter and the Frank and Dennis’ lust object Jackie Denardo (Jessica Collins) only muddies the gag up further, as Frank’s to-camera orders to Dennis now include claiming the woman’s “bagonzas” for his own and making silly faces with his mouth jammed full of fried fish. “Paddy Has Jumper” sets up the pieces for a classic bottle episode with the cop’s initial order “no one can enter or exit the building until the situation is resolved,” and it probably would have been better served by focusing the action inside the bar.

That’s because Dennis’ mind-exercise allows for Glenn Howerton, Charlie Day, Rob McElhenney, and Kaitlin Olson to do some especially funny character business as the four debate the inevitably selfish and tortuous reasoning involved. Taking the lead, Dennis gets to toss some kindling on the whole, smoldering “is Dennis a serial killer” debate, by bringing up damningly specific details about the falling death of his late, unlamented ex-wife, Maureen Ponderosa. (“Or at least he certainly made it look that way,” he ruminates ominously concerning the theory that someone was on that roof when cat-lady Maureen feel to er untimely death.) Asking the others how you can really know someone else’s mind leads to some telling answers like “go through their trash” (Charlie), “sleep with them” (Dee), and a very complicated plot to blackmail their priest with sex and then blackmail him again to get into heaven. (Guess.)

Some of Sunny’s best comedy comes from these situations, where an episode’s plot squeezes out more buried aspects of the Gang’s innermost weirdness, as, here, when Dennis’ perusal of the would-be jumper’s social media profile turns into an elaborately embroidered tale of love gone wrong over a widening disconnect regarding a certain sexual act. (“There’s a certain glint in the eyes, a certain sparkle,” muses Dennis as he runs his fingers over the face of the woman he’s absolutely convinced gradually soured on said sex act.)

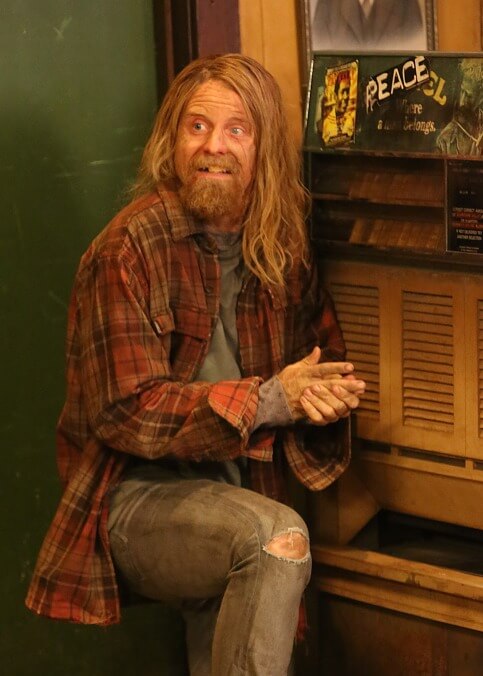

Resolution: Do nothing and go back to watching TV. That’s what happens when Frank’s unintentional ploy lures the jumper down with the promise of reunion with his estranged father. And that just as the rest of the Gang has really (if algorithmically) warmed to the idea that the only logical move here is to send the obliging Cricket up to the roof with a broom to ensure that Paddy’s becomes Philly’s cool new suicide bar hotspot. (Oh, Cricket’s lurking around the bar all episode.) And while it’s ever in keeping with Sunny’s commitment to both darkly comic callousness and the futility of looking for meaningful resolution in the Gang’s quickly heating-and-extinguishing passions, “Paddy’s Got A Jumper” pushes its conceit a bit too far into irrelevance, ultimately. Again, I think really focusing up on Dennis’ would-be mathematical approach to understanding and predicting messy humanity would have helped. There’s a window into Dennis’ own hardening need for control and mastery in the exercise that goes beyond the initial Netflix jokes into some promising dark comedy territory. (The Gang finally realizes that—algorithmic perfection be damned—Gainsborough Gardens sucks.) Sure, it might not have approached the D.E.N.N.I.S. System as far as chillingly hilarious Dennis Reynolds oversized-notepad presentation material goes, but it had that sort of vibe.

In the end, the jumper is at least temporarily safe, the Gang’s inaction alowing things to play out as they will. Charlie, coming as close to deconstructing just how horrifying the Gang is when left to figure out the right thing to do, admits, “I think this is for the best. We were goin’ down a road I was not totally comfortable with.” Meanwhile, Frank, digging his fingers grotesquely into that melon-hole, reveals that that’s where he hides his weed. (“Pot’s pretty much legal now, man,” observes Mac.) Oh, and he totally does have sex with it, as he, taking a bong hit, helpfully advises the hungry Cricket, “I wouldn’t eat it, Cricks. It’s full o’ loads.”

Airtight, mathematical conclusion: Funny, a little shaky, full o’ loads. As Dennis says at the end, “Perhaps the science just isn’t there yet.”

Stray observations

- What with Maureen (allegedly) and Bill (unsuccessfully) committing suicide thanks to their association with the Gang, the Ponderosa family continues to war with the McPoyles for family most likely to benefit from moving out of Philadelphia.

- The joke that Dee immediately snaps to filming the (helpful, black, female) police officer is a slyly pointed dig at how the Gang’s privilege extends to taking on other groups’ legitimate victimhood.

- Mac, in a slightly blunter joke: “I am an American! I can believe in whatever I want in any given moment based on the argument I’m trying to make!”

- Mac (real name Ronald McDonald) mocks Brian O’Brien for being named “like a clown.”

- Dee, suggesting that she has, in fact, given suicide more than a passing thought, ruminates on the jumper, “I think he’s just happy to get off this merry-go-round.”

- Charlie, as the gagging Dee spits out the egg she’s just scarfed down, “I think it’s a rat’s egg or something.”

- Not to undermine the indomitable black comedy of it all, but the Suicide Prevention Lifeline does good work.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.