Standing in full regalia at the edge of a beachfront, eyes fixed on the still waters sprawling out before him, Don Diego De Zama (Daniel Giménez Cacho) strikes the perfect image of the imperialist invader: rising from the sand like a red pillar of fusty decorum, as though he himself were a flag planted in colonized soil. But is there something more pitiful, a kind of hapless longing, in the direction and wistfulness of his gaze? Far from the mighty conquistador of legend, Zama is a lowly functionary, stationed—perhaps marooned would be the better word—in 18th-century Paraguay at the behest of the Spanish crown. He’s not proudly surveying his tropical fiefdom. He’s looking back at the water, conveying with every fiber of his overdressed being a burning desire to be anywhere else. This is the opening shot of Lucrecia Martel’s mysterious, confounding Zama, and we can tell, at an introductory glance, that we’re in for a portrait of a paradox: the life and times of the defeated conqueror.

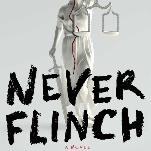

It’s one of several episodes pulled directly from Antonio Di Benedetto’s 1956 novel of the same name, which has become an essential cornerstone of Argentine literature. On screen, as on page, Zama is about stasis: the existential agony of being “Ready to go and not going,” as Di Benedetto put it. The story, a string of false starts and dead ends, doesn’t advance so much as shift back and forth, jogging lethargically in place. To emphasize Zama’s paralytic predicament, Zama deemphasizes the significance of his every action; scenes that feign towards moving the plot forward carry no more weight than those that simply exist to observe this cruel, absurd environment. Since nothing Zama does seems to get him any closer to what he so dearly desires, it’s appropriate that every moment unfolds with the same glancing ambivalence.

If the novel’s vision of a man stuck in time, place, and status seemed to anticipate its own obscurity (it took ages for it be recognized as a major work), the movie reflects Martel’s arduous process of adapting it. Nearly a decade has elapsed since the Argentine writer-director made a film—the bewildering thriller-cum-character-study The Headless Woman—and she spent much of the interim just trying to get this offbeat period piece off the ground; 16 production companies from all over the world ended up chipping in, resulting in a roll call of producers that includes Pedro Almodóvar, Danny Glover, and Gael García Bernal. The effort shows, in the right way: Why shouldn’t a film about thwarted goals possess the phantom impression of its own setbacks and delays? Zama, despite its setting, isn’t such a radical departure for Martel. It preserves her talent for tracking a frazzled individual through chaotic social spheres, such as the crowded hotel backdrop of The Holy Girl. And like The Headless Woman, it unfolds in a fugue state of privilege and distraction, achieved through a highly subjective sound design: Dialogue dips in volume or doubles back on itself to suggest very selective hearing.

In its own befuddling, bone-dry way, this is a comedy—one that takes fiendish pleasure in puncturing the pomp and circumstance of a cog in the empire-building machine. When the magistrate is unceremoniously booted from his digs (his belongings laid out in the open like those of an evicted tenant), he ends up having to relocate to the worst inn in Asunción: a backwater dump that even the proprietors believe is haunted. In another priceless ladling of insult atop injury, a naysaying fellow administrator (Juan Minujín) is “punished” with a transfer to the exact place where Zama hopes to go, and our hero’s quiet, simmering outrage (“The deported… gets to choose his destination?”) is punctuated by a stray lama that wanders into the room, mocking his misery by its very presence. Even the stylistic choices seem like jokes at Zama’s expense: The cheerful plucks of Spanish guitar and Martel’s gorgeous, painterly images suggest, with a tinge of bitter irony, that he’s somehow wandered into a much more romantic movie about his own life. Circumstance begs to differ.

It’s a risky endeavor, making itchy impatience a movie’s emotional bedrock. Surely, there will be those in the audience who will end up feeling as tortured, as cosmically pranked, as the title character. Zama does eventually liberate Zama from his prison of inertia, only to slyly toss him into a new one: an ill-fated manhunt through the wild, in search of a legendary, Godot-like bandit who may or may not exist. This striking epilogue, which gives the film’s exquisitely perturbed lead the bushy beard of a Cortés or a Pizarro, flips the prevailing tone of James Gray’s The Lost City Of Z from “Quixotic” to “Kafkaesque”—even the call of adventure doesn’t free our man from his station. But don’t cry too hard for Zama. As in The Headless Woman, Martel packs the margins with a marginalized underclass: in this case, the literally enslaved natives, whose own suffering in the background of every cluttered frame quietly dwarfs the protagonist’s petty problems. Maybe there’s a point here about weak, impotent men passing their humiliations down. Either way, save your sympathy. Purgatory isn’t hot enough for a colonialist.