They should have let Jason Bourne stay retired

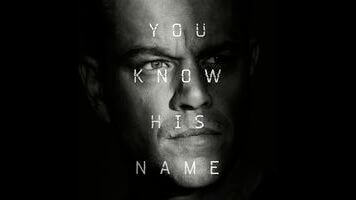

“I remember everything.” That’s the first line of dialogue in Jason Bourne, spoken over a black screen by the title character, presumably for the benefit of viewers who may have forgotten that everyone’s favorite amnesiac super-soldier finally regained his lost memories during his last mission. Bourne remembers everything, but will his audience? It’s been four years since the previous entry in this blockbuster franchise, and almost a decade since Matt Damon packed on some muscle and lost some levity to play Robert Ludlum’s signature spy. Those who don’t treat themselves to a “previously on” refresher may feel a little fuzzy themselves, the series coming back to them as a disorganized jumble of motorcycles racing down European alleys, desk jockeys yelling coordinates across blue-tinted control centers, and old white dudes furrowing their brows. It’ll all be a blur, just like the camerawork.

Jason Bourne presses Damon back into service, while also reenlisting director Paul Greengrass, who made the most acclaimed of the Bourne films, first sequel Supremacy and the trilogy-capping Ultimatum. Reuniting the two furthers the impression that this is a makeup movie, getting back to basics after The Bourne Legacy, which had the gall to remove Bourne from the equation entirely, replacing him with a new lab rat played by Jeremy Renner. But was that such a disastrous move for the series? Ultimatum brought the original character’s storyline to a proper conclusion, and Renner made a fine successor, his frazzled, junkie desperation (“The chems!”) an interesting pivot from the steeliness of Damon’s turn. Plus, director Tony Gilroy, who wrote every Bourne except this new one, staged the action with refreshing clarity. Jason Bourne fancies itself a course correction, but it’s really just a backslide: Rather than push this character or story forward, the film cravenly hits the reset button, doing more of the same with much less passion and skill.

Five films in, it could just be that the Bourne model—all the globetrotting silliness of 007, but with a gritty, geopolitical veneer—has started to look dispiritingly like a rigid formula. Draping itself in topicality, Jason Bourne takes aim at mass surveillance and data hacking, as former CIA stooge Nicky Parsons (Julia Stiles, completing her series-long crawl from bit player with a couple lines to bonafide Bourne sidekick) races to make public some black-op specs, in a leak the bureaucratic bigwigs insist could be “worse than Snowden.” Greengrass and cowriter Christopher Rouse spread their cynicism in all directions, reserving contempt for both the latest amoral big boss (Tommy Lee Jones, not providing this fugitive material with nearly enough Fugitive personality) and the sunken-featured Julian Assange-type planning to disclose the sensitive info. The film’s speedy plot also works in a flunky (Alicia Vikander) with shifting allegiances, the CEO (Riz Ahmed) of a vaguely defined social-media giant called Deep Dream, and another anti-Bourne assassin (Vincent Cassel), chasing our reluctantly roped-in hero from Berlin to London to Las Vegas.

The Bourne movies are popular for a reason. They’re brisk as hell, replacing the bombast of the typical Hollywood action movie with a sleek efficiency. And they privilege analog thrills—car chases, fistfights, suspenseful evasions in crowded public places—over digital fireworks. Yet there’s also something mechanical about their spy games: Taking its cues from the stoic professionalism of its headliner, the Bourne series pounds relentlessly from location to location, rarely pausing to take any joy in its own spectacle, to give its characters (good or bad) any flicker of personality. Having Greengrass back in the driver’s seat doesn’t help, frankly. By now, it’s basically a cliché to throw shade at his infamous disdain for the tripod. But the man still directs like he has a controlling share in Dramamine, confusing frenetic cut-a-second staging for a shortcut to urgency. At best, the set pieces in Jason Bourne feel like undercooked imitations of the franchise’s best; there’s no Waterloo chase to marvel over. At worst, they create uncomfortable real-world echoes (though it’s hardly Greengrass’ fault that viewers may have trouble watching an armored vehicle rampage through civilian traffic without thinking of recent headlines).

What Jason Bourne really has is a Jason Bourne problem. The character’s driven blankness, his total lack of psychology, made sense when he was still a man without a past. (In the underrated original, it actually made him rather likable, like a Hitchcockian wrong man.) But even with a full biography, Bourne is still just an empty cipher, devoid of any trait but determination; Greengrass attempts to give him a personal stake in the action—a new crusade for information, fueled by daddy issues—but it’s painfully clear now that there’s just no one there with Bourne, embodied by Damon through a complete suppression of his star charisma. Nor has age supplied the guy with any vulnerability; if anything, he’s only gotten more impossibly unstoppable, besting the full, Orwellian power of U.S. intelligence without breaking a sweat. Where’s the fun in a hero who can always outrun, outdrive, outfox, and outpunch his pursuers? Like his scrambling CIA handlers, the gatekeepers of this series might be best off just leaving Jason Bourne alone. He’s served his purpose. Time to let him go.