They should have taken the You’ve Got Mail route with this Lubitsch remake, Frantz

When Nora Ephron decided to remake Ernst Lubitsch’s 1940 classic The Shop Around The Corner, she chose to update the story as well, setting it in what was then the present day. That seems a bit funny now, as few Hollywood movies from the late ’90s feel more dated than You’ve Got Mail. (Today’s version would likely be titled U up?.) Still, the impulse was sound. A movie inevitably reflects the time at which it was conceived, and a brand-new yet doggedly faithful take on the same material won’t always put viewers in the right headspace to appreciate how it might have played to the audience for which it was intended.

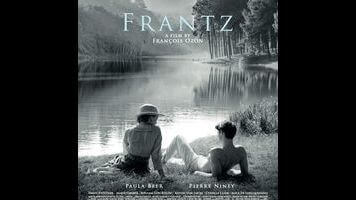

Frantz, the latest feature from prolific French director François Ozon (8 Women, In The House, Young & Beautiful), suffers from precisely that problem. The closing credits note that it’s “freely inspired” by Broken Lullaby, a film Lubitsch made for Paramount in 1932 (though the original source was a French stage play that had been adapted into English). Most cinephiles would rank Broken Lullaby well toward the bottom of Lubitsch’s filmography; it’s remembered primarily as a showcase for Lionel Barrymore. Even were the film a masterpiece, though, it would be an expressly post-war masterpiece. In 1932, the mutual anger felt by neighboring European countries, in the aftermath of what was then called the Great War, was still recent enough to resonate—less time had passed than has passed for us since 9/11. Watching Broken Lullaby, one can more readily enter that long-ago state of mind. Frantz, as a shiny new object that’s designed to look antique, feels more academic.

Set in 1919 and shot mostly in black and white (Ozon switches to color for flashbacks and—less consistently—during present-tense moments of happiness), the film begins in Germany, where a young woman named Anna (Paula Beer) regularly visits the grave of her fiancé, Frantz (played in flashbacks by Anton Von Lucke), who was killed on the battlefield. One day, she’s surprised to find that someone else has left flowers there. This turns out to be a Frenchman, Adrien (Pierre Niney), who says that he and Frantz had become friends while the latter was stationed in France. (The whole Frantz/France equivalence is less than subtle.) Anna introduces Adrien to Frantz’s parents (Ernst Stötzner and Marie Gruber), who are eager to hear stories about their son’s time in Paris; Anna and Adrien also start cozying up to each other. But Adrien harbors a dark secret, which the original play stuck right in its title.

Broken Lullaby—a significant departure for Lubitsch, whose forte was droll comedy—built to this tragic revelation, with Barrymore (in the role of the dead soldier’s father) almost inadvertently serving as the dominant figure. Frantz keeps the emphasis squarely on the younger characters, and places the big reveal almost precisely at the midpoint. Unfortunately, that leaves the film with nowhere much to go. Its second half, in which Anna travels to Paris in search of Adrien, consists of a whole lot of soporific sleuthing, and culminates in a second revelation that’s more of a damp squib. Even before that nosedive, though, Frantz struggles to compel, because its dramatic fulcrum—residual antagonism between Germany and France immediately after World War I—just doesn’t mean much to 21st-century filmgoers. It’s easy enough to grasp, but difficult to truly feel in the context of a modern-day period piece. Beer and Niney do solid work, but their sensitive efforts can’t quite breathe life into a story that no longer seems terribly relevant.