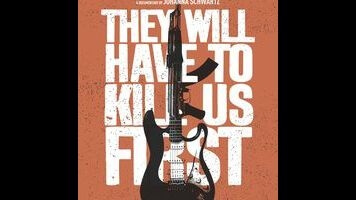

A stirring yet overstuffed documentary on musicians in exile, They Will Have To Kill Us First opens with a rundown of what happened in northern Mali in 2012—and refreshingly, it’s delivered in the form of a propulsive rap. That year, the National Movement For The Liberation Of Azawad (MNLA), a group fighting for the cause of the Tuareg ethnic minority, joined forces with jihadis to further its separatist ends; together, they repelled government forces—and took advantage of a destabilizing coup d’état—to declare independence in the Saharan north of that West African nation. Infighting between the MNLA and the Islamic extremists followed, ultimately allowing the latter to impose sharia law over a large swath of land encompassing the cities of Gao and Timbuktu. There, among a raft of other prohibitions, a ban on music took effect. A woman might well get 40 lashes just for singing, as does a character in last year’s Timbuktu, Abderrahmane Sissako’s superb drama about life under this very same fundamentalist rule.

Throughout They Will Have To Kill Us First, her debut feature, filmmaker Johanna Schwartz breaks down all this complex unrest without getting bogged down in explainer mode (or shying away from graphic footage). But the U.K.-based Schwartz above all turns out to be a deft portraitist—one who unfortunately gives herself a few too many characters to study. First tells the stories of no fewer than seven northern-Malian musicians who sought refuge in the south rather than be silenced altogether by the jihadis. Four relatively upbeat young men from Timbuktu have reconvened in the Malian capital of Bamako to form a guitar-based outfit called Songhoy Blues; Khaira Arby, a famous female vocalist, has also left Timbuktu for what appears to be a lonely existence in that same southern city. Meanwhile, an appealingly irrepressible singer known as Disco (a Madonna fan who’s been called that since high school) and a laconic guitarist named Moussa Sidi (a man from Gao whose wife has been imprisoned by that city’s new powers-that-be) bide their time at a refugee camp in the neighboring country of Burkina Faso.

In a stunner of a sequence early in the doc, Schwartz and cinematographer Karelle Walker capture the members of Songhoy Blues alongside the Niger at dusk, silhouetted against the dimming sky as they work out a beautifully circular song entreating those who’ve left Mali to return to repair the country. But not long thereafter these guys are traveling abroad themselves, if only for a brief spell. On a visit to Mali, Brian Eno and Yeah Yeah Yeahs guitarist Nick Zinner (both seen very briefly here) pay notice to Songhoy, and the band winds up jetting to England to sign a record deal and play a few victory-lap festival gigs. By this point, Khaira is courageously planning a concert of her own: a homecoming show in Timbuktu, which by early 2013 is unstable but no longer under the control of Islamic militants. When it comes time for that extraordinary occasion, though, the filmmaker is too busy wrapping everything up to linger and actually listen, just as she awkwardly cuts around the performances at an earlier event for Tuareg musicians at the Burkina Faso camp. Early in First, Khaira compares music to oxygen. The film might’ve felt a little more enlightening if all the songs had room to breathe in turn.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)