Thirst Street puts a smart stalker spin on ’70s-style European erotica

One of the more endearing quirks of 1970s European erotica is the persistent sense of danger. Adjust the lighting a bit, tweak the score just a few degrees from “dreamy” to “nightmarish,” and the typical French, Italian, Swedish, or Spanish skin flick from 40 years ago could just as easily pass as horror. After all, both genres—back then especially—were often about the anxieties of young women, thrust into situations fraught with excitement and personal peril.

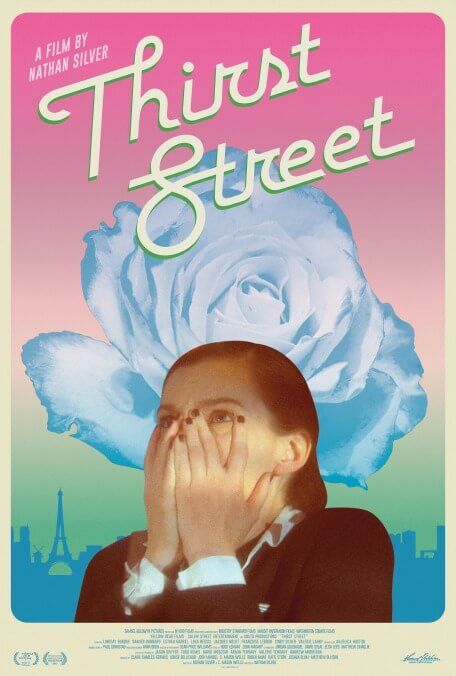

Writer-director Nathan Silver draws heavily on that hazy Eurotica atmosphere for his Thirst Street. Co-written with C. Mason Wells, the film follows a rootless American stewardess named Gina (Lindsay Burdge) as she reels from a recent romantic tragedy. While trying to pretend to her friends that everything’s okay, Gina has a brief fling with Jérôme (Damien Bonnard), a bartender at a Paris burlesque club. Increasingly unstable, she begins pretending that she and Jérôme are having a passionate affair. Eventually, Gina quits the airline, moves into an apartment across the street from Jérôme’s, and takes a job alongside him as a cocktail waitress.

Silver and Wells put multiple, sometimes competing spins on this material. Visually, a lot of Thirst Street is designed to look like a lost artifact from the Emmanuelle era, with soft lighting, luminous colors, and an emphasis on old-world elegance. Silver then warps that style, contrasting the heroine’s perception that she’s immersed in a sexy, classy Parisian adventure with the actual seediness of her surroundings, amplified by the mundanity of modern life. Every time someone pulls out a cellphone, or whenever Silver lingers over the painful case of pinkeye that Jérôme passed on to Gina, the retro-smut spell is broken—and wickedly so.

Thirst Street also puts on some literary airs, similar to the work of Silver and Wells’ fellow New York filmmaker Alex Ross Perry. Periodically, the voice of Anjelica Huston pops up, narrating the action as though she were reading from an eloquent slice-of-life novella, rich with detail and irony. In that same spirit, the movie follows a few world-building detours, including some extended scenes between Jérôme and his wary ex-girlfriend—a semi-popular rock singer named Clémence (Esther Garrel)—and a few comic interludes involving a pair of burlesque performers who keep making their routines edgier and more sociopolitically meaningful.

Even at 84 minutes, Thirst Street feels a little scattered and unfocused at times—likely as a consequence of its multiple layers of shtick. The movie finds time for a musical number, several stripteases, some noir-inflected cat-and-mouse, and one alternately heartbreaking and nerve-wracking dream sequence. There’s a lot going on here, and while the variety keeps the film lively, not all of it is seamlessly interwoven.

But Burdge holds the picture together, playing a character who walks a fine line between being sympathetically damaged and terrifyingly loony. Silver, Wells, and Burdge find a lot of dark comedy in the way that Gina’s pidgin French prevents her from understanding Clémence when she warns that Jérôme’s already taken, or from grasping that her boss at the club thinks she’s terrible at her job. While remaining fiercely committed to her fantasy, Gina sinks deeper into debt and dishevelment, and Thirst Street keeps squeezing humor, pathos, and tension out of her delusion.

It’s a sad, sick dynamic. Gina think she’s living through one of the gauzy softcore pics, wherein a naive young lady gets taught the ways of love by a worldly middle-aged man. But from Jérôme’s perspective? He’s stuck in Fatal Attraction.