This 19th-century baseball player still holds the record for most wins

This week’s entry: Old Hoss Radbourn

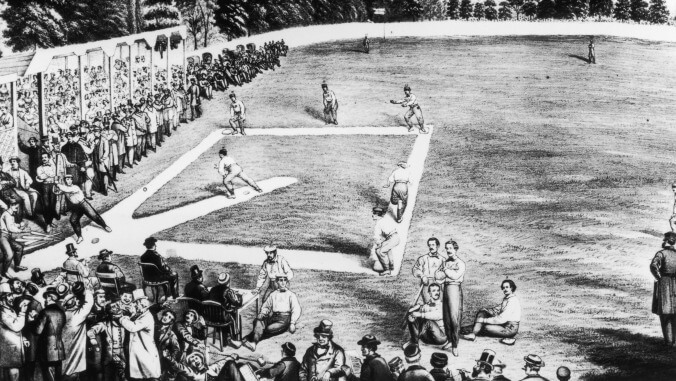

What it’s about: Everyone’s favorite 1880s baseball player. Charles Radbourn had old-timey baseball’s best nickname, best mustache, best legendary exploits, and set baseball’s most enduring record by winning 60 games in a season.

Biggest controversy: We’re not 100% sure how many games Old Hoss won in 1884. Sixty is the agree-upon number, according to the Hall of Fame, and the ultimate authorities in print (Baseball Encyclopedia) and online (baseball-reference.com). But MLB.com and baseball-almanac.com credit the pitcher with just 59 wins. Radbourn came in as a reliever in the sixth inning of a July 28 game, and the scorer ruled that he had been the most effective of the game’s three pitchers and awarded him the win. Under modern rules, the starter would have the win, so some sources don’t consider it a “real” win for Radbourn. (Wins and losses are usually awarded to the starting pitcher, although sometimes a reliever will get the credit or blame through some mysterious formula we don’t pretend to understand even after a lifetime of casually following the sport). Radbourn’s tombstone arrived at its own number, crediting him with 62 wins.

Strangest fact: There was a baseball strike so severe in 1890 that the players started their own league. After getting his start with the Buffalo Bisons and Providence Grays (early National League teams that both folded after the 1885 season), Old Hoss went to pitch for the Boston Beaneaters (which would become the Boston Braves, then the Milwaukee Braves, then the Atlanta Braves, then presumably a name less offensive to Native Americans a few years from now. We’re rooting for them to go with the Atlanta Beaneaters).

The National League had a reserve clause, which meant players couldn’t switch teams for more money, and a salary cap, limiting the amount of money a player could make for the same team. The league agreed to drop the salary cap in 1887 but reneged, so frustrated players staged a season-long walkout, and started their own eight-team league, the Players’ League. While most of the NL’s best players joined the new league and attendance was good, they didn’t have much financial backing, and the players decided to fold the league after one season. The irony is, their walkout hurt the rival American Association more than the National League—it would fold a few years later and while it was eventually replaced by the American League, in the meantime, the NL became the only game in town, giving it even more leverage with the players. The reserve clause remained in effect for another 85 years.

Thing we were happiest to learn: Old Hoss’ career almost ended before it began, but for a lucky second chance. He joined the 1878 Peoria Reds, playing right field and “change pitcher.” The early rules of baseball didn’t allow for substitutions, even on the pitcher’s mound, but players already on the field could switch positions. It was common practice to put a second pitcher in the outfield, so if the starting pitcher was getting shelled, a team could move him into the outfield, and bring its change pitcher in to save the day. Radbourn was good enough in this role that two seasons later, the then-major league Buffalo Bisons called him up to the bigs as a second baseman and change pitcher. But he practiced so hard that he hurt his shoulder and was released without ever taking the pitcher’s mound. (He played six games in the field and batted only .143.) His career was only saved because, while rehabbing his injury, he played a pickup game against the Providence Grays, who were so impressed that they signed him on the spot, and he was back in the majors.

Thing we were unhappiest to learn: He also needed a lucky third chance. In three seasons with the Grays, Radbourn established himself as one of the league’s best pitchers, finishing first or second in strikeouts, wins, and ERA in both 1882 and ’83. But the following year, Providence brought in another pitcher, Charlie Sweeney, who began to overshadow Old Hoss. Radbourn resented his teammate’s success, and the tension broke out into a fight—Radbourn was reportedly the instigator and was suspended without pay. But a week later, Sweeney showed up to a game drunk and continued drinking between innings. (Despite this, he still made it to the seventh inning, with the Grays up 6-2.) When the manager tried to swap him out for Radbourn, Sweeney cursed him out and was thrown out of the game. This left the Grays a man short, (remember, no substitutions meant there was no one on the bench waiting to come into the game), and they blew their lead.

Sweeney was fired. The prevailing view was that the team—already on shaky financial ground—should disband. But Radbourn saved the day by offering to pitch every single game in exchange for a small raise and an exemption from the reserve clause at season’s end. He then embarked on one of the most superhuman feats in baseball history, pitching 40 games in 60 days, winning 36. Modern pitchers generally get five days of rest between outings, and by late season Radbourn’s arm was so sore that he couldn’t comb his hair. But he finished the season having pitched 73 complete games, leading the league in wins, strikeouts, and ERA (the first two were sheer numbers, but a 1.38 ERA meant he was also dominating opposing batters during his grueling tenure). The Grays went on to play the American Association’s New York Metropolitans in the World Series.* Old Hoss started all three games of what was then a best-of-five series. He won all three, allowing only three unearned runs for the series.

*Major League Baseball considers the World Series to have begun in 1903, when the National League and American League champions faced off for the first time. But the 1884 game between the NL and AA was billed as the “World’s Series,” and was played annually until 1890, after which the AA folded, to be replaced by the AL in 1901.

Also noteworthy: Radbourn was able to save the season, but not the Grays. The team folded after the 1885 season, and Radborn signed with the Boston Beaneaters, then the Boston Reds of the Players’ League, then returned to the NL for one season with the Cincinnati Reds before retiring at age 36. He opened a successful billiards parlor and saloon, but soon after was injured in a hunting accident, losing an eye. He spent most of his years hiding out in a back room of the saloon, ashamed to be seen after his disfigurement. He died six years after retiring from baseball.

Best link to elsewhere on Wikipedia: The “charley horse” may have been named after Radbourn, as he suffered leg cramps during his playing days. He’s also the first person ever to be photographed giving the finger, as an 1886 team photo showed him sending a message to a New York Giants player. Flipping the bird is an unexpected cornerstone of Western civilization, as it first appeared in Ancient Greece “as a symbol of sexual intercourse, in a manner meant to degrade, intimidate and threaten the individual receiving the gesture,” as Wikipedia dryly puts it. Like many aspects of Ancient Greek culture, the gesture was embraced by the Roman Empire and endured long enough to be brought to America by Italian immigrants, where it was popularized just in time for the development of photography and Old Hoss’ second bid for immortality.

Further down the Wormhole: Radbourn is far from the only baseball Hall of Famer to have made an obscene gesture. Dick Williams, who played for five teams and managed six, was weeks away from being voted into the Hall when he was charged with indecent exposure, as he was accused of masturbating while naked on his hotel balcony. (He copped to the nudity but denied the masturbation; it will come as no surprise that the incident took place in Florida.) Wikipedia clinically describes indecent exposure as “the deliberate public exposure by a person of a portion of their body in a manner contrary to local standards of appropriate behavior.” It maybe not even be the most indecent thing one can do in public, as there’s also public pooping. Outside of a camping trip, public defecation is usually only done as a last resort. But for one woman, it was practically a hobby. We’ll meet The Mad Pooper next week.