In the Hulu comedy This Fool, it's always sunny in South Central

The Chris Estrada vehicle settles into a rhythm somewhere between a bilingual Modern Family and a less lesson-y Gentefied

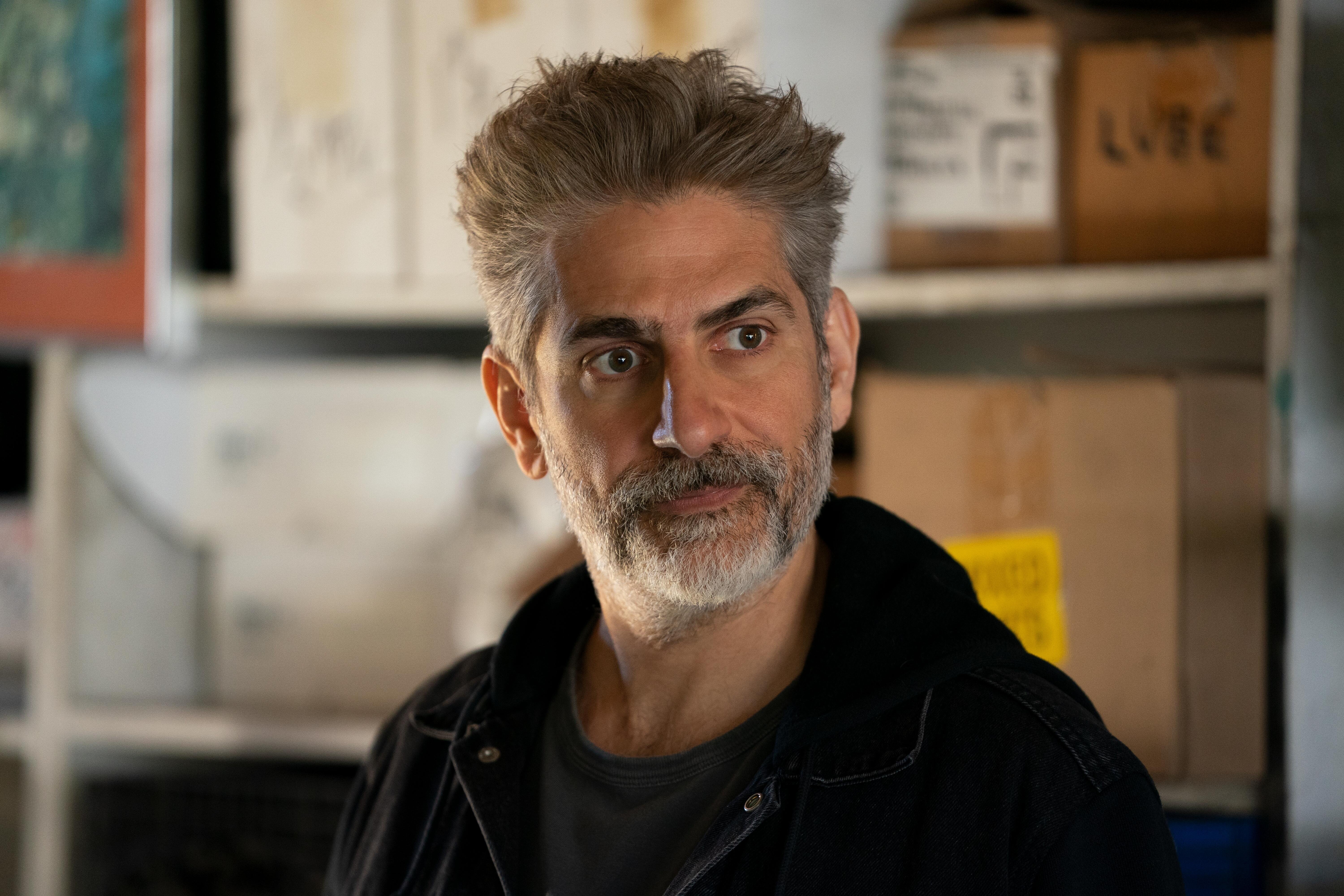

Nobody “motherfucker”-s like Michael Imperioli. The mother is draaawn out, fired with the snarl of a just-pulled lawnmower and peppered with a deep intestinal rancor, the fucker coming almost as the release, the exhale, the purr of pissed incredulity caused by whichever injustice the world has placed before him. In this case, it’s Richard Branson, or the “space knight motherfucker” who cheap-skated his donation to Hugs Not Thugs, the “fifth largest gangster rehabilitation center in Los Angeles” that was founded by Imperioli’s Minister Leonard Payne. It’s a welcome introduction to his character and a delightful reintroduction to the live-wire bits of frustration Imperioli cooked up as Christopher Moltisanti on The Sopranos. There he was one of the key comedic pieces on one of the funniest shows that nobody considered a capital-C comedy.

As it happens, here he’s one of the key comedic pieces on a show that leads with a much more troubling type of tonal confusion. In the first two episodes of This Fool, a drive-by is played for chuckles, a gang brawl is treated with nostalgic revelry by former members slowed by time and life and sciatic nerve hangups, and “Don’t Text And Drive” displays across the screen as an epitaph with operatic flippancy.

There’s also maybe a bigger conundrum facing the writers’ room, namely whether or not the comedy, in which Julio (Chris Estrada) counsels ex-cons, including his recently released cousin, is actually, you know, funny. It certainly can be, as in the front-loaded first episode, where intimidating men with face tattoos perform trust falls and Julio extolls the virtues of the place to a new arrival: “We remove more tattoos than anyone else in Los Angeles,” he says, adding that they offer “free legal counseling [and] solar-panel-installation classes.” Or later, when he describes why there’s no reason he couldn’t be Bourdain: “I’ve eaten foy gray before.” To which his ex-girlfriend, Maggie, replies, “You don’t even know how to pronounce foy gray.” Imperioli, for his part, steals most every one of his scenes, striking an early chord during an extended lecture on failure, all wide eyes and faux-wiseman profundity, his ability for humor amped by the ability to appear to take himself so stupidly serious.

The show can certainly also be, as many characters repeatedly chide, “corny.” A Salvadoran is irked by being called Mexican; a deceased friend nicknamed “Fatass” has, yes, “Fatass” inscribed on his urn. Vacillating between groan and cringe, Julio’s cousin, Luis (Frankie Quinones), peppers ceaseless ball-busting with “gay boy” and the likes of “y’all talk more than the motherfucking View” and, somehow, “you need a Viagra?” Perhaps it’s just more uneven than corny, more awkward than ha-ha, as smart as it is obvious, as oblivious as it is comfortable, taking real issues of modern L.A.—gun violence, gang culture—and setting them as backdrop thematic annoyances to be casually riffed on, as Bradley Newell might rap on a Sublime track.

Once the show settles, though, it finds a groove akin to the Chicano Batman theme that opens each episode. With the delightful reliance on old-school soul (Brenton Wood, Bill Withers) and palm trees and Dodgers decorum and shit-shooting around the dining room table with elderly relatives, a lived-in flow emerges, and the show lands on a rhythm somewhere between a bilingual Modern Family and a less lesson-y Gentefied. The stakes are mostly low, it’s always sunny in South Central, even when meeting “at the park at sundown” for a brawl, and by the fourth episode even the tightest of TV reviewers may do very well to take Julio’s epiphany to heart: “How about this? I’ll stop being a little bitch.”

At that point anyone can appreciate the physical humor of, say, Julio giving his nephews fireworks to shoot off to distract the family so he can slink away from birthday engagements, or Luis putting Julio in a headlock to keep him in place while the family sings “Feliz Cumpleanos,” or an elaborate and preposterous slow-motion ball-kicking scene, or an episode-long homage to Austin Powers.

Estrada, who co-created the show and used his real life as inspiration, plays Julio with the same button-down, clean-shaven, subtly pomaded nice guy turn that fills his standup persona. He is mocked for having “lawyer hands,” is seen by his abuela as someone “always crying, just a little bit.” He is a man who sincerely and fully enjoys his pour-over coffee situation, coming off as alternatively sweet and cloying. (“The life expectancy of a gangster on average is 24 years old, but the life expectancy of a punk ass bitch, 76 years old,” he informs.) He’s both bighearted and his use of “big dawg” renders him some varying mix of jovial and punch-worthy.

As his on-again-off-again ex, Michelle Ortiz breathes fire into the manic-pixie-ex-girlfriend template, with high-pitched outbursts turning to raunchily smitten tenderness. She steals/borrows Julio’s Accord before berating him that the Check Engine light is on, hitting with lines like “we’ve had sex in the backseat, it’s our car.” She interrupts his date to get him to come over to help find a disappeared pet bunny, a la Annie Hall’s spider-in-the-bathroom scene, eventually trying to coax him to stay with “I got Wendy’s.” In the obvious spirit of yin-yang buddy comedies, Luis seems overtly ex-con doltish, overplaying the easy parts, leaning brashly into the casual homophobia. It’s not 2005, as he is constantly reminded—“Tobey Maguire ain’t Spiderman no more” Julio tells him—but has he been in prison or a coma? In 2005, were we still making Viagra jokes and asking “does that make your boyfriend jealous?”

Yes, it is a show about redemption, about tempering recidivism with good cupcake sales. “People love buying cupcakes from ex-gang members,” states Imperioli in one of his many steely deadpans. “If girl scouts ever start getting face tattoos, we’re fucked.” And it is about family, however annoying they sometimes might be. These are the standard themes of any harmless Thursday-night family sitcom. Of course, you can watch this one when you want, as one of the best back-and-forths between Luis and his ex-fiancé reminds us:

“You’re a fucking loser with a weird dick.”

“Fuck you, curvy dicks are normal.”

“You know Judge Judy will rule in my favor.”

“Her show is over, idiot.”

“She’s got a new one, idiot.”

“What time? I wanna watch.”

“It’s streaming so it’s available whenever.”

Within such ping-pong banter is where This Fool finds its pocket. Like when Imperioli, uber-stoic, over-intense, gets asked about his documentary, Game Set Hope, a chronicle of an actual ping-pong tournament on Skid Row. A tagline at the bottom of the poster for the film that hangs in his office declares: “A film you might soon forget, but shouldn’t.” And that’s how it feels like things might go for this show. Once a rhythm is achieved, though, This Fool is joyously funny because of what it’s really about, what it’s really asking: Who will watch your shitty documentary, even though they think there’s too much flute in the soundtrack? Who cares enough to steal you toilet paper from work, even if it is single-ply? Who makes you your favorite Tres Leches cake, even though you hate your birthday? Who shows up for you, even if a “homegirl” stole their Honda? And who will you stand by, even when he won’t stop quoting Austin Powers?