This is not going to go the way you think: The Last Jedi and the necessary disappointment of epilogues

This article discusses major plot points from both Star Wars: The Force Awakens and Star Wars: The Last Jedi.

Luke Skywalker is old. When we see him in The Last Jedi, the former golden boy who once gazed at the sky and dreamed of adventure is now a bedraggled gray hermit who just wants to be left alone, looking and sounding like a cross between True Grit’s John Wayne and Monty Python’s “It’s” man. He’s holed up on his remote island, alone with his guilt and his memories, milking the sour teats of dolorous alien hippos with a primitive, nihilistic gusto. He’s broken, having seen everything he’s ever accomplished—everything that made him a legend—rendered meaningless by the rise of yet another evil Empire under a much lamer name. All that he ever fought for, everyone he lost in the process (his aunt and uncle, his mentor, even his own father) was ultimately for nothing, because everything’s right back where it was. And then, he dies.

Han Solo is even older. When we see him in The Force Awakens, the handsome rogue who’d finally found his true calling, along with the first loyal, genuine friends he’s ever known (Chewbacca excepted, of course) is right back where we first met him. Nothing could be sadder. As a senior citizen, the whole “scoundrel” thing is significantly less charming now. He may still bear some trace of that same wry, Harrison Ford grin, but the swagger is noticeably gone. There’s something a little pathetic about the fact that Han’s still wearing his cool-guy leather jacket, hanging out with his old running dog-buddy, still out there swindling petty cargo loads to make ends meet. He was a general, for space-God’s sake; he’d captained an epochal, galaxy-saving campaign and fallen in love with a princess. Yet just a few decades later, he’s lost her, he’s lost his son, and he’s even lost the Millennium Falcon. He can’t even schmooze his way out of a minor jam with some generic space-hoods. And then, he dies.

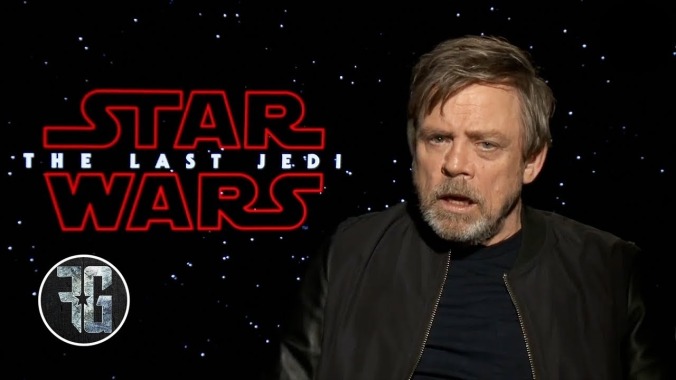

Among the complaints about The Last Jedi (and there have been many), the one that seems to carry the most weight with self-proclaimed “true” Star Wars fans is that Rian Johnson’s film dishonors Luke Skywalker’s legacy—even more so than J.J. Abrams’ tarnishes Han Solo’s, who at least seems comfortable back in rock bottom. It’s an argument that’s been lent some unexpected weight by none other than Luke Skywalker himself: A popular video that’s currently making the rounds, at 1.79 million views and climbing, cobbles together dozens of interview clips ostensibly proving that “Mark Hamill Hates Star Wars: The Last Jedi.” In them, Hamill seemingly bemoans the fact that these new films are being handled by “children;” he suggests a complete rewrite of The Force Awakens, in which Luke swoops in heroically to save Leia just in time to witness Han’s death “instead of two characters who have known him, what, 20 minutes;” and he laments the new franchise’s box-office success being mistaken for it being any “good.”

Though he’s long had this kind of dryly candid, self-deprecating sense of humor about him, here Hamill actually comes off kind of… bitter. And in tandem with other interviews where he recalls telling director Rian Johnson, “I think I fundamentally disagree with everything you’ve decided for me,” you could certainly build a case that Hamill isn’t just joking around, that he actually feels like he’s been railroaded by newer, younger filmmakers and money-hungry execs who have no respect for him or the stories they’re building on.

But then, this is always the risk—and the inevitable disappointment—of epilogues. When Disney first acquired Lucasfilm and announced a new series of movies to take place after Return Of The Jedi, it was an implicit announcement that the victory our heroes had achieved, the one that fans had been celebrating for decades as an example of light always winning out against the dark, was about to be undone. Star Wars fans had dealt with this idea before in the post-Jedi stories of the Expanded Universe, in which new threats arose to take up the mantle of the not-wholly-vanquished Empire. But there Luke, Han, Leia, et al. were still young-ish and virile, and imbued with the lasting confidence of their win. They—and we—knew there wasn’t anything they couldn’t handle now, and there was little to challenge that notion—or to upset ROTJ’s perfect holiday photo ending of them all basking in their triumph while the Ewoks drummed joyfully on the hollowed-out skulls of the Stormtroopers they just ate. (They definitely ate them.) It’s why, when George Lucas decided there was more story to tell, he retreated to the safety of history, knowing there would still be that happy ending out there waiting. Nothing can erase that.

And yet, that’s not how life works. Victories fade, replaced by new challenges. Heroes get older. They become broken-down and kind of pathetic, bearded and cynical. Sometimes they even end up all alone, stewing over decades-old fuck-ups, suckling at the nipples of sad, mutant cows. Happy endings are always undone because “endings” don’t really exist. Time doesn’t stop when you want it to. Your “destiny” can and will be slowly eroded away by the many small, cumulative abrasions of life that inevitably follow after you achieve it. This is real, and it’s disillusioning, and it can fill you with righteous anger at the unjustness of it all. And then, you die.

In tackling this notion head-on—in being willing to not only challenge Star Wars’ happy ending, but to question whether happy endings actually exist—these new films are giving the saga something that it’s always somewhat lacked, even in all its constant grappling with themes of the spirit versus the machine: humanity. That’s not always an easy fit with the kinds of myths that Star Wars updates; rarely do we talk about the fact that Hercules, for example, triumphed over his Twelve Labors, only to end up a twice-married widower who got killed by a shirt. And the very idea of it pisses off people who cling to the illusion that their own hero’s journey will someday be “complete.”

And yet, that’s the story of life. We get to what seems like a comfortable end—married with children, say, accomplished in our careers, content to just let things remain status quo forever. Then life intrudes, because we’re only one small chapter within its story. Those things change and slip away. We may “fundamentally disagree” with what life decides for us. Life writes its epilogue anyway.

The Last Jedi tells us this explicitly, time and again—even right there in the trailer. “Let the past die. Kill it, if you have to,” Kylo Ren says to Rey. “This is not going to go the way you think,” Luke tells her earlier.

Most have rightly identified these as meta commentaries on the new movies themselves: These films aren’t going to play by the rules of familial destiny, Chosen One narratives, and all the other myths Joseph Campbell deconstructed decades ago and that George Lucas popularized for a new generation of films. In order for Star Wars to continue at all, it has to undo, if not outright destroy, the story that came before—to burn the “sacred texts,” as The Last Jedi does in one of its other, more on-the-nose moments.

Otherwise, what story is there to tell? Luke becomes even more the self-possessed, slightly New Age-y bore he was in Return Of The Jedi, dutifully passing on his wisdom to a new generation of Jedi trainees? Han and Leia’s marriage suffers the occasional strains, but mostly they’re happy in love? All of them have to intermittently band together against another Palpatine wannabe whom they—and we—know will ultimately be vanquished, because they already did this once? Star Wars: And Everything Was Pretty Much Fine is not a particularly compelling tale to hang a new generation of movies on.

At the same time, despite how it might make us feel—we “true” Star Wars fans, Mark Hamill, anyone who aches for the death of our heroes and the asterisk that now stands next to their sacrifices—it’s become clear over time that this is the story the Star Wars saga was always trying to tell. The first film’s subtitle, A New Hope, hints at its very cyclical nature. In the prequels, Anakin was that new hope: “You were the Chosen One!” Obi-wan Kenobi shouts at Anakin with all the frustration of someone who thought this war was finally about to end, that the loss of his own friends and mentors would ultimately mean something. In Rogue One, “hope” comes in the form of the Death Star plans, obtained at great cost to yet more lives, which are handed off to Princess Leia in the final scene—“hope” that then becomes about Leia cajoling Obi-wan Kenobi into rediscovering his own, and in turn, passing it along to Luke. Even the “new hope” that Luke Skywalker represented would have to be renewed several times over, watered by the blood of countless soldiers and Bothan spies. And it led to what was, really, only the temporary defeat of a planet-destroying battle station that the Empire just went and built a couple more times anyway.

In The Last Jedi, that new hope comes full circle as Luke—in his own Kenobi-like, self-imposed exile—first rejects its pull as a “cheap move,” before he, too, ultimately sacrifices himself in its name. By movie’s end, “hope” is the small spark that’s still burning in the handful of Resistance survivors who are once more beating retreat on the Millennium Falcon, reconvening their decimated numbers to plot what comes next, That hope persists, even as we are left with the crushing, real-world knowledge that the last of our old heroes up there on the screen won’t be around to carry it through.

It’s depressing, and it’s galling, and to some angry fans, it’s needlessly cruel. But it’s also the truest and most important thing this space fantasy has ever said. The need for “a new hope” never ends, and that’s exhausting. It’s frustrating. It doesn’t seem like it should be that way—certainly not in the stories we tell ourselves to distract us from such realities. Certainly not in a year where, for so many, it feels like we just emerged from a period of “hope” only to find ourselves right back at the bottom again, waiting for a new one to come along. In that same Mark Hamill video, he even hits upon this note while discussing just how quickly the old ’60s hippie delusions faded: “There’ll be no more wars! We’ll end world famine! Hey baby, love is all you need… We failed! And now the world is worse than it’s ever been.” We’re still at war, people are still hungry (and about to get hungrier), and Mark Hamill is having his own inspirational words thrown back at him by Ted Cruz. This epilogue is pure garbage. It’s full of plot holes and senseless contrivances and it sucks.

But then, that’s life. That’s how stories go—all of them. We evolve, for better and, probably more often, for worse. And we are always at war. In being willing to tell us that, at a time when we arguably need to hear it most—at a time when Star Wars’ original fans are entering middle age, and our culture is increasingly feeding us the kind of nostalgic comfort that can leave us dangerously entrenched and emotionally stunted, unable to cope with change—The Last Jedi gave us this heartbreaking, enraging, utterly bullshit enrichment of Star Wars as one of our most vital modern myths. What comes next will surely also be tragic and moving and triumphant and, ultimately, meaningless. I can’t wait to see it.